Worthy Down Aerodrome

Written by Richard Hall

As the myriad of dog walkers, joggers, ramblers and even the chap flying his model aircraft enjoy the open space of rolling hills and tracks that border South Wonston, how many of them will know the history of the land upon which they stand. There is very little at this 480-acre site to suggest that the area was once used for aviation. Even the one remaining intact Dutch Barn hangar looks like an ordinary agricultural building. However, look a little deeper, and the signs are still there, but more of that later

It’s suspected few will know that the tracks and paths upon which they walk, run, ramble were once home to the aircraft of the Royal Flying Corps (RFC), Royal Air Force (RAF) and the Fleet Air Arm (FAA). Do the residents of the vast housing estate that sits on the edge of the former aerodrome, ever look out from their windows across the former landing ground and visualise the test flying of Spitfires; in all likelihood no.

Not many people would be aware that Winchester used to have its own horse racing course, this was located at a place called Worthy Down. Situated two and a half miles north of the Wessex Capital in the rolling Hampshire countryside, it was not an obvious place to build an airfield due to the terrain. But in the early days of aviation, aircraft would take off in any direction as long as it was into wind. Worthy Down Airfield was a grass strip built on undulating ground 345 feet above sea level. The slopes and type of land at this field would have made landing and taking off ‘interesting’.

The airfield had a long history and first came into existence in 1917 towards the end of the First World War. The former Winchester Racecourse was acquired for use by the Wireless and Observers School (W&OS), who were compelled to vacate Brooklands due to the expansion at the site in aircraft manufacturing. The racecourse is recorded in use from April 1664, although no evidence exists about the races held there until a two-day event shows up in records for August 1676. The site remained in use until July 1887, after which it was abandoned. Further information relating to the racecourse can be found here: hostmaster.greyhoundderby.com

The main technical buildings at Worthy Down consisted of six large Aeroplane sheds, an Aeroplane Repair and Salvage hangar. These were built close to the Didcot Newbury and Southampton Railway, which ran along the airfield’s eastern boundary. By this time, the W&OS had moved to Hursley Park, which itself in 1940 became Vickers-Armstrong’s Management and Design Office for Spitfire dispersed production, following the heavy Luftwaffe raids on Supermarine’s manufacturing plant at Woolston near Southampton, in September of the same year.

As the myriad of dog walkers, joggers, ramblers and even the chap flying his model aircraft enjoy the open space of rolling hills and tracks that border South Wonston, how many of them will know the history of the land upon which they stand. There is very little at this 480-acre site to suggest that the area was once used for aviation. Even the one remaining intact Dutch Barn hangar looks like an ordinary agricultural building. However, look a little deeper, and the signs are still there, but more of that later

It’s suspected few will know that the tracks and paths upon which they walk, run, ramble were once home to the aircraft of the Royal Flying Corps (RFC), Royal Air Force (RAF) and the Fleet Air Arm (FAA). Do the residents of the vast housing estate that sits on the edge of the former aerodrome, ever look out from their windows across the former landing ground and visualise the test flying of Spitfires; in all likelihood no.

Not many people would be aware that Winchester used to have its own horse racing course, this was located at a place called Worthy Down. Situated two and a half miles north of the Wessex Capital in the rolling Hampshire countryside, it was not an obvious place to build an airfield due to the terrain. But in the early days of aviation, aircraft would take off in any direction as long as it was into wind. Worthy Down Airfield was a grass strip built on undulating ground 345 feet above sea level. The slopes and type of land at this field would have made landing and taking off ‘interesting’.

The airfield had a long history and first came into existence in 1917 towards the end of the First World War. The former Winchester Racecourse was acquired for use by the Wireless and Observers School (W&OS), who were compelled to vacate Brooklands due to the expansion at the site in aircraft manufacturing. The racecourse is recorded in use from April 1664, although no evidence exists about the races held there until a two-day event shows up in records for August 1676. The site remained in use until July 1887, after which it was abandoned. Further information relating to the racecourse can be found here: hostmaster.greyhoundderby.com

The main technical buildings at Worthy Down consisted of six large Aeroplane sheds, an Aeroplane Repair and Salvage hangar. These were built close to the Didcot Newbury and Southampton Railway, which ran along the airfield’s eastern boundary. By this time, the W&OS had moved to Hursley Park, which itself in 1940 became Vickers-Armstrong’s Management and Design Office for Spitfire dispersed production, following the heavy Luftwaffe raids on Supermarine’s manufacturing plant at Woolston near Southampton, in September of the same year.

|

Construction of the airfield proceeded through the latter part of 1917. The W&OS became the Artillery and Infantry Co-operation School/Squadron (A&ICS) on 12 October 1917, with the units flying elements at Worthy Down by December of the same year.

The unit was equipped with Royal Aircraft Factory R.E.8, Avro 504J/K, Bristol F.2B, B.E.2D, F.K.3, DH.9 and Sopwith Camels. |

From a logbook of an unnamed RFC pilot, flying at Worthy Down in December 1917. On the 23rd of the month, the pilot recorded that he was flying a Royal Aircraft Factory R.E.8 serial number 7001 on a flight from the airfield to Crawley, Whitchurch, Andover and Winchester. He flew at the height of 3,000ft and broke an axle upon landing. On 27 December, he was again flying 7001 at an altitude of 2,000ft again over Whitchurch and Andover. This time he observes the engine ran rough, and it was bumpy in the air. Of note, the logbook is signed off with a stamp on 30 December 1917, the title of which is Wireless and Observers School, somewhat odd as the school changed its name earlier in the year.

It had not been easy for the early aviators to make their mark. The Royal Navy and the British Army could see no real use for aircraft and regarded them as a bit of a novelty, with dubious military value. This view would be quickly dispelled with the coming of the First World War, where an eye in the sky could yield valuable results when charting the course and composition of one's enemy. Reconnaissance machines soon became feared over the battlefield and at sea, where they could be used to see and spot over the horizon. The appearance of such airborne craft would often result in a barrage of shells raining down on an enemy's positions or ships. Co-operation between the land and air assets was of utmost importance, and the need to train pilots/wireless operators became an urgent priority. The lives of crews flying army co-operation missions were often in peril as the evolution of scout aircraft (fighters) made the skies over the trenches a dangerous place to be, many were lost.

The accommodation blocks and administration sections were essentially complete at Worthy Down when the airfield officially opened in 1918, which was a momentous year for Britain's military aviation with the formation of the RAF on 1 April. The day before, on 31 May 1918, the A&ICS's HQ and ground training elements joined the flying unit at the airfield from Hursley Park. The A&ICS was renamed the RAF and Army Co-operation School (R&ACS) on 19 September of the same year.

The accommodation blocks and administration sections were essentially complete at Worthy Down when the airfield officially opened in 1918, which was a momentous year for Britain's military aviation with the formation of the RAF on 1 April. The day before, on 31 May 1918, the A&ICS's HQ and ground training elements joined the flying unit at the airfield from Hursley Park. The A&ICS was renamed the RAF and Army Co-operation School (R&ACS) on 19 September of the same year.

|

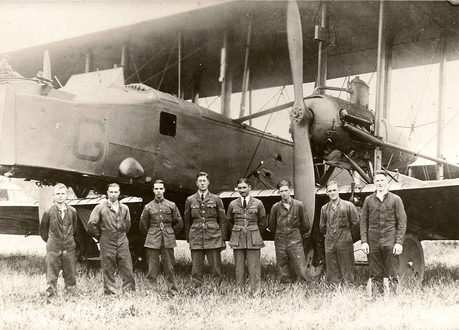

The unit acted as a finishing school for Corps Reconnaissance pilots after they had graduated 'B' at their training school. The men were taught advanced Artillery and Infantry Co-operation, Contact Patrol and map reading. The School also received Corps Reconnaissance Observers at the end of their training and qualified them for their Observer Wings. The unit consisted of 20 Armstrong Whitworth F.K.8, 12 Bristol F.2B Fighter (pictured left) and 50 R.E.8 aircraft, personnel on-site amounted to some 1,450.

|

With the Armistice coming at this time, very little happened at Worthy Down, there were plans to build an airfield at nearby Flowerdown for No 1 (Training) Wireless School, which arrived there in August 1918, but this did not come to fruition. Although no airfield was built, any requirement for flying by the school was handled by Worthy Down as part of the RAF's Inland Area Command (IAC). Renamed No 1 (Training) Wireless Squadron in March 1919, the unit was equipped with AW F.K.8 and Bristol F.2Bs.

In December 1919, the unit was re-designated the Electrical and Wireless School (E&WS) with a detached flight at Worthy Down. The E&WS was located away from the main site near the former A34 road, opposite Worthy Grove. Contemporary photos show wooden accommodation huts and two Bessonneau hangars with aircraft parked outside, in essence creating a separate airfield.

The school remained here until July 1930, at which time it moved to RAF Cranwell. Incidentally, Flowerdown was used throughout World War Two as a listening station that fed information to Bletchley Park and after the war, as GCHQ's Composite Signals Organisation became a large HF listening station, finally closing in the late 1970s.

In December 1919, the unit was re-designated the Electrical and Wireless School (E&WS) with a detached flight at Worthy Down. The E&WS was located away from the main site near the former A34 road, opposite Worthy Grove. Contemporary photos show wooden accommodation huts and two Bessonneau hangars with aircraft parked outside, in essence creating a separate airfield.

The school remained here until July 1930, at which time it moved to RAF Cranwell. Incidentally, Flowerdown was used throughout World War Two as a listening station that fed information to Bletchley Park and after the war, as GCHQ's Composite Signals Organisation became a large HF listening station, finally closing in the late 1970s.

With the conclusion of the First World War, thoughts turned to peace, and the need for airfields diminished. Worthy Down's existence now hung in the balance. Memories of the war, in which millions of lives were lost on all sides, were still uppermost in the minds of the military and public alike. There was little appetite to increase air assets or any other military assets for that matter. The RAF continued to fly aircraft that was a throwback to the earlier years of military aviation.

|

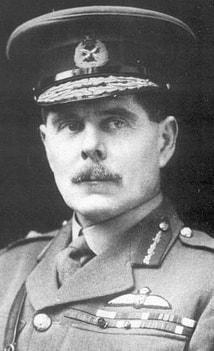

Following the end of hostilities, the man who was to become Marshal of the Royal Air Force, Sir Hugh Trenchard, was fighting off attempts by the Admiralty and the Army to liquidate the RAF.

To this end, he contented himself with consolidating his somewhat outdated fighting aircraft and made the best of what he had at his disposal to ensure the RAF survived. Against the odds, it did, which was very fortunate as in a mere 20 years, the RAF would hold the key to Britain's survival. |

One of the reasons, but not the only for the RAF's continued existence, was its ability to subdue rebellious tribes in Britain's Empire, at minimal cost over the previous measures used. The mere presence of an aircraft and a few bombs were enough to keep the most determined of tribesmen's heads down. The accountants, true to form, saw this as a cost-effective method and a cheaper alternative to sending in the army, so the RAF, albeit in a reduced form, was reprieved from imminent extinction. In August 1919, the British government brought in the Ten Year Rule, which assumed that the Empire would not face a major conflict for a decade. How anyone could foresee what would happen in the future was not clear, but defence spending was cut, and it would be some time before any expansion took place.

A detachment from the Artillery Co-operation Squadron (ACS) came to the airfield in July 1919 from Stonehenge, under the command of 11 Training Depot Squadron. The R&ACS was redesignated the School of Army Co-operation (SoAC) as part of Inland Area, 7 Group, on 23 December 1919 and remained at Worthy Down until 8 March 1920, on which day it was disbanded along with the ACS. The SoAC reformed on the same day and absorbed the ACS, relocating to Stonehenge with a flight of Bristol F.2Bs remaining on detachment at their former home airfield. The School remained at the Wiltshire airfield before relocating to Old Sarum on 9 February 1921. Worthy Down was now in a state of Care and Maintenance, with no resident units based there. At this time, many former World War One airfields disappeared off the map. This one survived, as political and world events that were to come in a few short years would give it a new lease of life.

A detachment from the Artillery Co-operation Squadron (ACS) came to the airfield in July 1919 from Stonehenge, under the command of 11 Training Depot Squadron. The R&ACS was redesignated the School of Army Co-operation (SoAC) as part of Inland Area, 7 Group, on 23 December 1919 and remained at Worthy Down until 8 March 1920, on which day it was disbanded along with the ACS. The SoAC reformed on the same day and absorbed the ACS, relocating to Stonehenge with a flight of Bristol F.2Bs remaining on detachment at their former home airfield. The School remained at the Wiltshire airfield before relocating to Old Sarum on 9 February 1921. Worthy Down was now in a state of Care and Maintenance, with no resident units based there. At this time, many former World War One airfields disappeared off the map. This one survived, as political and world events that were to come in a few short years would give it a new lease of life.

Air Defence of Great Britain

The RAF's strength following the end of the war reduced by around 90%. In 1922 the War Office was concerned that France had an air force double the home nation's size. Although there was little likelihood of war with France, the difference in strength did not sit well, and it was decided parity should be achieved. As a result of the recommendations of the Steel-Bartholomew Committee in 1923, it was concluded that responsibility for homeland air defence be transferred from the War Office to the Air Ministry. This led to the creation of the Command known as Air Defence of Great Britain (ADGB), whose assets included fighters, bombers, anti-aircraft guns, searchlights and the Observer Corps. In April 1925, the IAC was in the process of being split with part forming the ADGB Command, although, at this time, the latter had no units assigned. Trenchard proposed that that ADGB should have 52 squadrons, which would consist of 17 fighters units and 35 of bombers. Things did not go to plan, and by 1930, the RAF had 17 fighter squadrons and 12 bomber.

The RAF's strength following the end of the war reduced by around 90%. In 1922 the War Office was concerned that France had an air force double the home nation's size. Although there was little likelihood of war with France, the difference in strength did not sit well, and it was decided parity should be achieved. As a result of the recommendations of the Steel-Bartholomew Committee in 1923, it was concluded that responsibility for homeland air defence be transferred from the War Office to the Air Ministry. This led to the creation of the Command known as Air Defence of Great Britain (ADGB), whose assets included fighters, bombers, anti-aircraft guns, searchlights and the Observer Corps. In April 1925, the IAC was in the process of being split with part forming the ADGB Command, although, at this time, the latter had no units assigned. Trenchard proposed that that ADGB should have 52 squadrons, which would consist of 17 fighters units and 35 of bombers. Things did not go to plan, and by 1930, the RAF had 17 fighter squadrons and 12 bomber.

|

Awakening from a period of relative quiet in 1924, 58 (Bombing) Squadron was formed at Worthy Down on 1 April with a single flight of Vickers Vimy heavy bombers as part of Inland Area, 7 Group. A second flight was created on 1 January 1925 and by March of the same year, conversion to Vickers Virginia III night bombers was underway. The Virginia was powered by two Napier Lion engines and could carry a 1,000Ib bomb load over a range of around 1,000 miles. The aircraft was crewed by a pilot, navigator and two gunners.

|

On 3 May 1926, a General Strike of all transport workers, rail workers and miners was called. No 58(B) Squadron was pressed into service to carry Members of Parliament, troops and mail. The unit received favourable comments from the Air Officer Commanding in Chief ADGB for their work and efficiency during the strike.

By July 1926, the ADGB was split into two sections, the Wessex Bombing Area (HQ Andover), consisting of nine bomber squadrons and the Fighting Area (HQ Uxbridge), with twelve units and one-night flying flight. Worthy Down was within the Wessex Bombing Area, together with 58(B) Squadron. The Electrical and Wireless School at Flowerdown remained with the IAC as part of No 23 Group (HQ Spittlegate).

By July 1926, the ADGB was split into two sections, the Wessex Bombing Area (HQ Andover), consisting of nine bomber squadrons and the Fighting Area (HQ Uxbridge), with twelve units and one-night flying flight. Worthy Down was within the Wessex Bombing Area, together with 58(B) Squadron. The Electrical and Wireless School at Flowerdown remained with the IAC as part of No 23 Group (HQ Spittlegate).

|

On 7 April 1927, 7 (Bombing) Squadron arrived from RAF Bircham Newton as part of the Wessex Bombing Area, ADGB, again flying the Virginia.

Up until 1935, either one of the two squadrons held the Lawrence Minot Memorial Bombing Trophy, which is suspected of having led to a fair amount of rivalry between the two units. It is interesting to note that 7(B) Squadron was commanded by Wg Cdr C F A Portal, who rose to the post of Chief of Air Staff 1940 - 1945. |

|

From late May 1925, 58(B) Squadron was commanded by Sqn Ldr (later Sir) Arthur T Harris AFC, who became Commander in Chief RAF Bomber Command 1942 - 1945. Harris recognised very early on that the present-day bombers were woefully ill-equipped to fly over enemy territory in daylight and would have been easy prey to fighters. To this end, Harris spent many nights at Worthy Down with 58 honing their night flying skills. In his owns words, "I reckon we did more night than all the rest of the air forces in the world put together."

A diary entry from someone who lived near the airfield at this time states that they were being kept awake by the night flying Worthy Down based bombers. It's nice when this type of eyewitness account is unearthed so many years later. Harris spent nearly two and a half years at Worthy Down, where his ability as a very able pilot and leader was recognised. This stood him in good stead when he led Bomber Command in World War Two, from February 1942 to September 1945. |

He was also known to be outspoken and proved to be utterly determined to succeed in the tasks given to him. This quality was sorely needed through those challenging days of the RAF's strategic bombing campaign. Sometimes he was a little too determined, which would cause him problems and gain him, enemies in the forthcoming war. But, at the time, he was the right man for the job, and it is only with the benefit of hindsight that some have levelled ill-judged criticism at him.

The rivalry between Harris and Portal continued during the war when the pair frequently locked horns over strategy and the bomber campaign. Also at Worthy Down with Harris was Robert Saundby (later Sir), one of 58 (B) Squadron's flight commanders. He went on to serve under Harris as his deputy during Harris's time as C-in-C Bomber Command. One of Saundby's interests was collecting butterflies, something he undoubtedly indulged in while at Worthy Down with abundant nearby fields. Harris relinquished his squadron command on 4 November 1927 to Wg Cdr E W Norton DSC.

While based at Worthy Down, both Harris and Portal were in close contact with Ralph Cochrane, who was Training Staff Officer for the Wessex Bombing Area. Like his two associates, Cochrane would go on to serve in World War Two as Air Officer Commanding of 5 Group, Bomber Command, from February 1943 through to February 1945. One of his first tasks with 5 Group was to supervise Operation Chastise, or as it's more well known, 'The Dambusters Raid'.

The rivalry between Harris and Portal continued during the war when the pair frequently locked horns over strategy and the bomber campaign. Also at Worthy Down with Harris was Robert Saundby (later Sir), one of 58 (B) Squadron's flight commanders. He went on to serve under Harris as his deputy during Harris's time as C-in-C Bomber Command. One of Saundby's interests was collecting butterflies, something he undoubtedly indulged in while at Worthy Down with abundant nearby fields. Harris relinquished his squadron command on 4 November 1927 to Wg Cdr E W Norton DSC.

While based at Worthy Down, both Harris and Portal were in close contact with Ralph Cochrane, who was Training Staff Officer for the Wessex Bombing Area. Like his two associates, Cochrane would go on to serve in World War Two as Air Officer Commanding of 5 Group, Bomber Command, from February 1943 through to February 1945. One of his first tasks with 5 Group was to supervise Operation Chastise, or as it's more well known, 'The Dambusters Raid'.

Storm Clouds Gather

As the decade of the 1930s progressed, the signs of a future war were starting to be seen. The causes could be traced back to the Treaty of Versailles signed in 1919, Italian Fascism in the 1920s, aggressive military adventurism by the Japanese in the 1930s and by no means least the rise of the National Socialist German Workers Party (Nazis), which took full dictatorial power in the country in 1934, upon the death of President Hindenburg. Led by Adolf Hitler, the Nazis continually disregarded the terms of the Treaty of Versailles by rearming, reintroducing conscription and taking back territories it had conceded under the Treaty's terms. There was very little in reaction from the League of Nations (a worldwide organisation set up after the First World War to maintain world peace). Hitler, emboldened by this fact, continued to see how far he could push to achieve his goals.

There was alarm in Britain at the build-up of potentially hostile forces that could threaten its Empire. In 1932 the Ten Year Rule was abolished, but it would still be some years before the country began to build up its forces. When the RAF started to expand, the aircraft types brought into production were in the main not suitable to take on the modern Luftwaffe. This was especially true regarding bombers, which were slow, outgunned and unable to carry a heavy bomb load. It was fortuitous that Britain did rearm with the Supermarine Spitfire and Hawker Hurricane, as without these two aircraft, the country's future would have been much in doubt. There is no questioning the bravery of the bomber crews, but it would not be until the start of the Second World War in September 1939 that weakness in Britain's aircraft design would become all too evident.

There was alarm in Britain at the build-up of potentially hostile forces that could threaten its Empire. In 1932 the Ten Year Rule was abolished, but it would still be some years before the country began to build up its forces. When the RAF started to expand, the aircraft types brought into production were in the main not suitable to take on the modern Luftwaffe. This was especially true regarding bombers, which were slow, outgunned and unable to carry a heavy bomb load. It was fortuitous that Britain did rearm with the Supermarine Spitfire and Hawker Hurricane, as without these two aircraft, the country's future would have been much in doubt. There is no questioning the bravery of the bomber crews, but it would not be until the start of the Second World War in September 1939 that weakness in Britain's aircraft design would become all too evident.

In April 1935, 7(B) Squadron began conversion onto Rolls-Royce Kestrel powered Handley Page Heyford II bombers (similar to the photograph on the left).

During August and September of the same year, 2, 4 and 13 (AC) Squadrons briefly detached to the airfield with Hawker Audax to carry out army co-operation flights.

'B' Flight of 7(B) Squadron formed into 102(B) Squadron on 1 October 1935 equipping with the Heyford II, while at the same time, 'A' Flight of 58 became 215(B) Squadron and continued to fly the Virginia.

|

'B' Flight carried on as No 58(B) Squadron and left for Upper Heyford along with 215(B) Squadron in mid-January 1936, taking their Virginias with them. The two squadrons then became part of ADGB, No 3 (Bomber) Group. On 14 July 1936, Bomber Command was formed with 7(B) and 102(B) Squadron leaving Worthy Down for Finningley on 3 September of the same year. Hawker Hinds of 49(B) Squadron arrived on 8 August 1936 from Bircham Newton, under the command of 3 (Bomber) Group.

|

On 24 January 1937, the Hawker Hinds of 104 (B) Squadron deployed from Hucknall for two weeks to carry out high altitude bombing practice at Porton. Following on 24 April of the same year, 98(B) Squadron was attached from Hucknall, again to carry out high altitude bombing. During July and September 1937, 35(B) and 207(B) Squadron re-equipped with Vickers Wellesley bombers. This brought a more complex aircraft with retractable undercarriage, variable pitch propeller and an enormous wingspan. All three squadrons were now under the command of 2 (Bomber) Group.

On 14 March 1938, 49(B) Squadron left for RAF Scampton to re-equip with Handley Page Hampden bombers, an aircraft they were to use in the opening years of World War Two. Their first operation on 3 September 1939 was an armed reconnaissance over the North Sea. One of the units long term pilots, Flt Lt Roderick 'Babe' Learoyd, who had served at Worthy Down, went on to win a Victoria Cross, the second for Bomber Command of the war, for a raid on the Dortmund Ems Canal on 12/13 August 1940. While at Scampton in April 1942, the squadron converted onto the Avro Manchester, an aircraft that later was to gain a poor reputation due to its inadequate Rolls-Royce Vulture powerplants. Although the Manchester was a liability, it did provide the basis for the Avro Lancaster, which turned out to be a world-beater. The squadron flew the Manchester until June 1942 when it converted to the Lancaster, an aircraft it was to fly with great success throughout the rest of the war.

On 20 April 1938, 207(B) Squadron relocated to Cottesmore in Rutland, where it converted to the Fairey Battle, a light bomber powered by a single 1,030hp Rolls-Royce Merlin engine. The Battle was a woefully inadequate aircraft and was obsolete when it entered service. Consequently, it suffered heavy losses during the Battle of France in May 1940. The machine was used in a training role by 207(B) Squadron until April 1940, when the unit was absorbed by 12 Operational Training Unit. The squadron reformed at Waddington on 1 November 1940, where it converted to the Manchester and carried out its first operation to bomb a Hipper class cruiser in Brest Harbour on 24/25 April 1942. Re-equipping with the Lancaster in March 1942, the units last operation along with 49(B) Squadron was to bomb Hitler's mountain retreat at Berchtesgaden on 25 April 1945.

On 14 March 1938, 49(B) Squadron left for RAF Scampton to re-equip with Handley Page Hampden bombers, an aircraft they were to use in the opening years of World War Two. Their first operation on 3 September 1939 was an armed reconnaissance over the North Sea. One of the units long term pilots, Flt Lt Roderick 'Babe' Learoyd, who had served at Worthy Down, went on to win a Victoria Cross, the second for Bomber Command of the war, for a raid on the Dortmund Ems Canal on 12/13 August 1940. While at Scampton in April 1942, the squadron converted onto the Avro Manchester, an aircraft that later was to gain a poor reputation due to its inadequate Rolls-Royce Vulture powerplants. Although the Manchester was a liability, it did provide the basis for the Avro Lancaster, which turned out to be a world-beater. The squadron flew the Manchester until June 1942 when it converted to the Lancaster, an aircraft it was to fly with great success throughout the rest of the war.

On 20 April 1938, 207(B) Squadron relocated to Cottesmore in Rutland, where it converted to the Fairey Battle, a light bomber powered by a single 1,030hp Rolls-Royce Merlin engine. The Battle was a woefully inadequate aircraft and was obsolete when it entered service. Consequently, it suffered heavy losses during the Battle of France in May 1940. The machine was used in a training role by 207(B) Squadron until April 1940, when the unit was absorbed by 12 Operational Training Unit. The squadron reformed at Waddington on 1 November 1940, where it converted to the Manchester and carried out its first operation to bomb a Hipper class cruiser in Brest Harbour on 24/25 April 1942. Re-equipping with the Lancaster in March 1942, the units last operation along with 49(B) Squadron was to bomb Hitler's mountain retreat at Berchtesgaden on 25 April 1945.

|

It is of note that 35(B) Squadron's ORB states that in April 1938, the first dual control Fairey Battle (K7695) was received by the unit at Worthy Down. The squadron left for Cottesmore on 21 April 1938 and went on to play a vital role in World War Two. Initially flying Battles in a training role, the unit re-equipped with Bristol Blenheims before being absorbed by 17 OTU. Reforming in November 1940 with Handley Page Halifax heavy bombers, one of the unit's pilots was Fg Off (later Group Captain) Leonard Cheshire, a man who made quite a name for himself within Bomber Command and went on to win a Victoria Cross.

|

To improve bombing performance, the Pathfinders were formed in August 1942, 35(B) Squadron was picked as one of the five units that made up the nucleus of the new force. Later in the war, the squadron converted to the Avro Lancaster and flew its last operation of the war on 25 April 1945, with a raid against the gun batteries at Wangerooge.

All the bomber squadrons based at Worthy Down flew throughout the war and distinguished themselves with honour. Bomber Command started the conflict with outmoded aircraft and flawed tactics. Losses were high, and results were disappointing. It was not until Harris took over in February 1942 that the tide started to turn, and the Command began to meet its full potential. An advocate of night bombing, Harris knew the risks of daylight raids where enemy fighters would be present. His many hours of night flying at Worthy Down helped to mould the tactics used many years later in the Command's strategic bombing campaign over Europe. A problematic, strong-minded character, but without him and his subordinates, the war's course could have been very different.

All the bomber squadrons based at Worthy Down flew throughout the war and distinguished themselves with honour. Bomber Command started the conflict with outmoded aircraft and flawed tactics. Losses were high, and results were disappointing. It was not until Harris took over in February 1942 that the tide started to turn, and the Command began to meet its full potential. An advocate of night bombing, Harris knew the risks of daylight raids where enemy fighters would be present. His many hours of night flying at Worthy Down helped to mould the tactics used many years later in the Command's strategic bombing campaign over Europe. A problematic, strong-minded character, but without him and his subordinates, the war's course could have been very different.

|

In April 1938, Worthy Down transferred from Bomber to Coastal Command's 17 (Training) Group. The first units to arrive were Avro Ansons of 206(GR), 220(GR) and 233 (GR) Squadron for exercises with HMS Centurion (King George V class battleship) during July. Also moving in the Hawker Nimrods and Hawker Ospreys of 800(F) Squadron and some trial Gloster Gladiators. In November 1938, 803 Squadron formed with Blackburn Skua fighter/dive bombers.

|

|

A requirement for fighter affiliation exercises with 228 (GR) Squadron, who were based at Lee-on-the-Solent, was met on 19 November 1938 with the arrival for a two-week stay of Gloster Gladiator Is from 'B Flight' 25(F) Squadron. The unit returned to their home airfield of Hawkinge on 3 December, their place taken by 'A' Flight, who stayed for a further week. Hawkinge would later play a significant part in the Battle of Britain and today is home to a superb museum that records the momentous air battle in the summer and autumn of 1940.

The museum is well worth a visit - www.kbobm.org |

The Fleet Air Arm, HMS Kestrel and Spitfires

|

On 24 May 1939, Worthy Down was officially handed over to the Admiralty and named HMS Kestrel. The field became home to the 1 Telegraphist Air Gunners School (TAG). No 1 Air Gunners School came shortly afterwards with three flying units, Nos 755, 756 and 757, equipped with Blackburn Shark and Hawker Ospreys. For a brief period between 29 June 1939 and 29 July of the same year, 814 Squadron, a Torpedo Spotter Reconnaissance unit, brought their Fairey Swordfish in before deploying to HMS Ark Royal.

|

Hitler, at this time, continued to see how far he could pursue his goals, and up until now, he had suffered little in the way of consequences for his aggression. However, his invasion of Poland on 1 September 1939 was a step too far and resulted in Britain and France declaring war on Germany on 3 September 1939.

The TAG School was still resident when war broke out and was joined at the airfield by the survivors of 811 and 822 Squadron following the sinking of the carrier HMS Courageous (torpedoed by U-29 on 17 September 1939). The two units amalgamated to become 815 Squadron (Swordfish I) before disbanding again in November 1939 and merging with 774 Squadron.

The TAG School was still resident when war broke out and was joined at the airfield by the survivors of 811 and 822 Squadron following the sinking of the carrier HMS Courageous (torpedoed by U-29 on 17 September 1939). The two units amalgamated to become 815 Squadron (Swordfish I) before disbanding again in November 1939 and merging with 774 Squadron.

|

Between 10 to 16 November 1939, 774 Squadron formed at the site as an Armament Training Squadron for observers, with a selection of Sharks, Skuas, Rocs and Swordfish.

The unit was equipped by taking aircraft and personnel from 782 and 815 Squadrons and storage. To say their stay was brief would be an understatement, as they had left for Aldergrove within six days. |

On 1 February 1940, 806 Squadron formed at Worthy Down as a fighter unit equipped with four Blackburn Skuas and four Rocs. The squadron moved to Hatston on 28 March of the same year and undertook bombing operations against oil targets at Bergen during the Norwegian Campaign. Following the German invasion of Norway on 9 April 1940, the carrier HMS Glorious was ordered back to Britain from Alexandria. One of the ship's squadrons, 825, disembarked and flew to Worthy Down on 4 May 1940.

Since the war began on 3 September 1939, there had been little in the way of action on the Continent. However, this all changed on 10 May 1940 when Hitler launched his Blitzkrieg against the Low Countries and France, catching the Allies completely off guard. The TAG School, which had moved to Jersey on 11 March, swiftly returned to Worthy Down as the Germans overran France.

Since the war began on 3 September 1939, there had been little in the way of action on the Continent. However, this all changed on 10 May 1940 when Hitler launched his Blitzkrieg against the Low Countries and France, catching the Allies completely off guard. The TAG School, which had moved to Jersey on 11 March, swiftly returned to Worthy Down as the Germans overran France.

|

The British and French armies were pushed back towards the Channel coast, which led to the evacuation at Dunkirk. After returning from Hatston on 26 May 1940, 806 Squadron deployed the following day from Worthy Down to RNAS Detling to lend their assistance in covering the withdrawal from the beaches.

Also deploying to Detling were 825 Squadron, commanded by Lt Cdr Eugene Esmonde. The situation was desperate, which led to the unit's Swordfish undertaking operations outside of their usual remit. |

By the end of May and June, it was carrying out bombing raids against gun batteries, tanks and transport in the Calais area and spotting for the guns of HMS Arethusa. In such a hostile environment, 825 lost eight aircraft and were withdrawn back to Worthy Down in early July 1940, leaving on 5 September to embark on HMS Furious. Esmonde was later to win a DSO for a torpedo attack on the 52,000-ton German battleship, Bismarck, on 24 May 1941, which he led with eight Swordfish of 825 NAS flying from HMS Victorious.

During this attack, the squadron scored one confirmed hit on the ship when a torpedo struck the armoured belt just below the waterline. The damage was minimal, and it fell to 818 NAS flying from HMS Ark Royal to land a mortal blow the following day, when a torpedo struck the ship's rudder, jamming it in a 15 degree turn to port. Unable to manoeuver, Bismark was sunk on 27 May 1941 by a Royal Navy task force.

Esmonde would go on to win a posthumous Victoria Cross for his heroic leadership during the Channel Dash on 12 February 1942, details of which can be found by following this link: www.airshowspresent.com

Returning to their home airfield, 806's pilots collected the first Fairey Fulmar aircraft to enter service and then left for Eastleigh to undergo further training. The Rolls-Royce Merlin-powered Fulmar was designed as a carrier-borne fighter/reconnaissance aircraft crewed by a pilot and observer.

During this attack, the squadron scored one confirmed hit on the ship when a torpedo struck the armoured belt just below the waterline. The damage was minimal, and it fell to 818 NAS flying from HMS Ark Royal to land a mortal blow the following day, when a torpedo struck the ship's rudder, jamming it in a 15 degree turn to port. Unable to manoeuver, Bismark was sunk on 27 May 1941 by a Royal Navy task force.

Esmonde would go on to win a posthumous Victoria Cross for his heroic leadership during the Channel Dash on 12 February 1942, details of which can be found by following this link: www.airshowspresent.com

Returning to their home airfield, 806's pilots collected the first Fairey Fulmar aircraft to enter service and then left for Eastleigh to undergo further training. The Rolls-Royce Merlin-powered Fulmar was designed as a carrier-borne fighter/reconnaissance aircraft crewed by a pilot and observer.

|

After the Fall of France in June 1940, there was a brief respite of around six weeks before the Battle of Britain began. On 1 July 1940, 808 Squadron formed at the airfield equipping with Fulmar Is.

They were present during the Battle of Britain but were not called upon to participate in the fight with the Luftwaffe in southern skies. The unit moved to Castletown on 5 September 1940 to protect Royal Navy assets at Scapa Flow from potential aerial attack. |

As the threat of attacks on airfields from the Luftwaffe escalated, decoys were constructed to draw the attention of enemy aircraft to sites where the dropping of bombs would cause little in the way of material damage. Worthy Down's Q/QF decoy site was constructed approximately three miles northeast on open land near the village of Micheldever.

With his victory in France complete, Hitler was convinced the British would see the hopelessness of their position and would come to terms. Churchill was having none of it and vowed to fight on. The Battle of Britain began on 10 July 1940, and at this time, Luftwaffe attacks were mainly targeted against shipping in the English Channel and ports with some inland bombing raids. The objectives for these attacks had been set out in Hitler Directives No 9, Instructions for Warfare Against the Economy of the Enemy, and No 13, issued on 29 November 1939 and 24 May 1940, respectively. The first of these Directives detailed the most effective means to ensure the crippling of the English economy, and the second authorised attacks against the British homeland, shipping and a host of other assets, as referenced in Directive No 9.

The attacks aimed to deprive Britain of the means to fight by stopping imports for the war effort and denying access to the waters. It also attempted to bring the RAF into the skies to weaken it through attrition. The results were slow in coming when it was considered the number of vessels using the Channel. Although there were losses to the Luftwaffe attacks, Britain showed no signs of capitulating, so this could be seen as a failure to achieve the objective of pacifying the nation by denying it supplies. Hitler was growing impatient with the stubborn British and concluded invasion may be necessary. To this end, on 16 July 1940, he issued Directive No 16, On Preparations for a Landing Operation Against England. He states:

Since England, in spite of her hopeless military situation, shows no signs of being ready to come to an understanding, I have decided to prepare a landing operation against England and, if necessary, to carry it out.

On the first day of August, he issued Directive No 17, For The Conduct of Air and Sea Warfare Against England:

In order to establish the necessary conditions for the final conquest of England I intend to intensify air and sea warfare against the English homeland.

This Directive called for the Luftwaffe to gain air superiority over the Channel and mainland to allow an unhindered invasion to proceed. Part of the plan was to attack airfields which commenced on 13 August 1940 and was given the name Adlertag (Eagle Day). Although Hermann Göring, head of the Luftwaffe, was confident his air force could sweep the RAF's fighters from the skies, history in time would prove him wrong.

On 15 August 1940, Worthy Down found itself a target of Directive No 17 when the Luftwaffe sent Junkers Ju88A-1s of I/LG1 and II/LG1 from Orleans-Bricy to attack targets in the south of England. The raid was escorted by Messerschmitt Bf 110s of II/ZG76. Despite the constant attention of Hurricanes and Spitfires from 43, 249, 601 and 609 Squadrons over Southampton and the Solent, the raiders eventually got through. In the early evening, the airfield was dive-bombed by II/LG1, causing little in the way of damage. An eyewitness account states a few broken windows, lights and a car windscreen. However, the cost to the Luftwaffe was high, including the loss of five Ju88s to 601 Squadron. The site defences also put up a good show, with a Lewis gun party on a hangar claiming hits on the bombers. Interestingly a gun turret from a Blackburn Roc had been pressed into service and claimed strikes, as did Maxim gun crews.

Middle Wallop was also bombed with minimal effect; the Luftwaffe would have done better to concentrate their efforts on this airfield as it was a critical Fighter Command Sector Station. Worthy Down was, however, not a fighter station, so it's unclear why it was targeted. German intelligence was clearly lacking, and a number of airfields were attacked, where the effect of lessening fighter strength was not going to be achieved. The Luftwaffe had planned that Worthy Down was to be targeted on Eagle Day itself by II/LG1, but poor weather and fighter opposition saved it this day.

The 15 August was a bad day for the Luftwaffe and was known to the crews as Black Thursday. On this day, the RAF lost 34 fighters, but for the German's 75 aircraft did not return from the over 2,000 sorties flown. At a later date, Lord Haw-Haw was to make one of his more notorious remarks when he informed the British public that HMS Kestrel had been bombed and sunk. This undoubtedly caused some amusement to the station personnel, whose feet were obviously still dry.

While Worthy Down had been lucky to escape damage, the Supermarine Factory at Woolston was less so. On Tuesday, 24 September 1940, the Luftwaffe attacked the complex, killing or injuring many workers but not putting the plant out of action. Two days later, the Luftwaffe struck again and caused more serious damage to Spitfire manufacturing.

Following this, urgent dispersal of Spitfire production became a priority and arrangements were hastily implemented. It was fortunate that the machinery and jigs at Woolston were not destroyed by the bombing. This enabled the equipment to be moved to allow dispersed production. The ingenuity shown was incredible as all manner of premises were commandeered to produce the many thousands of components that make up a Spitfire.

With his victory in France complete, Hitler was convinced the British would see the hopelessness of their position and would come to terms. Churchill was having none of it and vowed to fight on. The Battle of Britain began on 10 July 1940, and at this time, Luftwaffe attacks were mainly targeted against shipping in the English Channel and ports with some inland bombing raids. The objectives for these attacks had been set out in Hitler Directives No 9, Instructions for Warfare Against the Economy of the Enemy, and No 13, issued on 29 November 1939 and 24 May 1940, respectively. The first of these Directives detailed the most effective means to ensure the crippling of the English economy, and the second authorised attacks against the British homeland, shipping and a host of other assets, as referenced in Directive No 9.

The attacks aimed to deprive Britain of the means to fight by stopping imports for the war effort and denying access to the waters. It also attempted to bring the RAF into the skies to weaken it through attrition. The results were slow in coming when it was considered the number of vessels using the Channel. Although there were losses to the Luftwaffe attacks, Britain showed no signs of capitulating, so this could be seen as a failure to achieve the objective of pacifying the nation by denying it supplies. Hitler was growing impatient with the stubborn British and concluded invasion may be necessary. To this end, on 16 July 1940, he issued Directive No 16, On Preparations for a Landing Operation Against England. He states:

Since England, in spite of her hopeless military situation, shows no signs of being ready to come to an understanding, I have decided to prepare a landing operation against England and, if necessary, to carry it out.

On the first day of August, he issued Directive No 17, For The Conduct of Air and Sea Warfare Against England:

In order to establish the necessary conditions for the final conquest of England I intend to intensify air and sea warfare against the English homeland.

This Directive called for the Luftwaffe to gain air superiority over the Channel and mainland to allow an unhindered invasion to proceed. Part of the plan was to attack airfields which commenced on 13 August 1940 and was given the name Adlertag (Eagle Day). Although Hermann Göring, head of the Luftwaffe, was confident his air force could sweep the RAF's fighters from the skies, history in time would prove him wrong.

On 15 August 1940, Worthy Down found itself a target of Directive No 17 when the Luftwaffe sent Junkers Ju88A-1s of I/LG1 and II/LG1 from Orleans-Bricy to attack targets in the south of England. The raid was escorted by Messerschmitt Bf 110s of II/ZG76. Despite the constant attention of Hurricanes and Spitfires from 43, 249, 601 and 609 Squadrons over Southampton and the Solent, the raiders eventually got through. In the early evening, the airfield was dive-bombed by II/LG1, causing little in the way of damage. An eyewitness account states a few broken windows, lights and a car windscreen. However, the cost to the Luftwaffe was high, including the loss of five Ju88s to 601 Squadron. The site defences also put up a good show, with a Lewis gun party on a hangar claiming hits on the bombers. Interestingly a gun turret from a Blackburn Roc had been pressed into service and claimed strikes, as did Maxim gun crews.

Middle Wallop was also bombed with minimal effect; the Luftwaffe would have done better to concentrate their efforts on this airfield as it was a critical Fighter Command Sector Station. Worthy Down was, however, not a fighter station, so it's unclear why it was targeted. German intelligence was clearly lacking, and a number of airfields were attacked, where the effect of lessening fighter strength was not going to be achieved. The Luftwaffe had planned that Worthy Down was to be targeted on Eagle Day itself by II/LG1, but poor weather and fighter opposition saved it this day.

The 15 August was a bad day for the Luftwaffe and was known to the crews as Black Thursday. On this day, the RAF lost 34 fighters, but for the German's 75 aircraft did not return from the over 2,000 sorties flown. At a later date, Lord Haw-Haw was to make one of his more notorious remarks when he informed the British public that HMS Kestrel had been bombed and sunk. This undoubtedly caused some amusement to the station personnel, whose feet were obviously still dry.

While Worthy Down had been lucky to escape damage, the Supermarine Factory at Woolston was less so. On Tuesday, 24 September 1940, the Luftwaffe attacked the complex, killing or injuring many workers but not putting the plant out of action. Two days later, the Luftwaffe struck again and caused more serious damage to Spitfire manufacturing.

Following this, urgent dispersal of Spitfire production became a priority and arrangements were hastily implemented. It was fortunate that the machinery and jigs at Woolston were not destroyed by the bombing. This enabled the equipment to be moved to allow dispersed production. The ingenuity shown was incredible as all manner of premises were commandeered to produce the many thousands of components that make up a Spitfire.

|

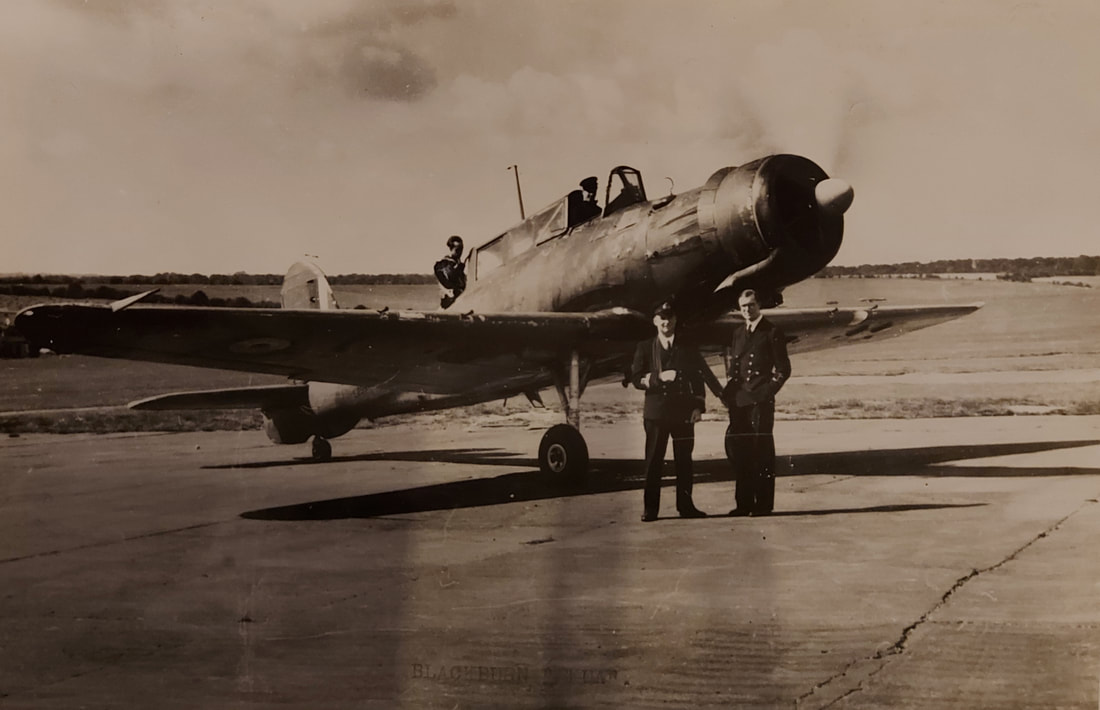

Two Bellman Hangars became available at Worthy Down, and in December 1940, Spitfire development flying was moved to the airfield with Jeffrey Quill, chief test pilot for Vickers-Armstrong, placed in charge.

In addition, Spitfires from dispersed sites such as Chattis Hill were flown into Worthy Down for flight testing and onward transit to frontline squadrons. |

In early 1941 a sizeable dispersed storage facility was created to the west of the airfield. The site was accessed by a taxiway from the main airfield that crossed the A34 road into Worthy Grove. The crossing was controlled by airmen who used railway style gates to close the road during aircraft movements into the area containing 48 Dutch Barn, 2 Bessoneaux and a Fromson hangar. Three Quetta Huts used by the airmen and in varying states of collapse can still be found near the site's entrances.

The TAG School activity continued with a number of changes taking place among the squadrons. Although 756 Squadron had been absorbed into 755 Squadron by August 1939, on 6 March 1941, 756 reformed in its own right as an advanced section of the school. The squadron flew Percival Proctor aircraft but was again absorbed by 755 on 1 December 1942.

By July 1941, a shortage of spares for 755 Squadron's elderly Shark aircraft was becoming apparent. To overcome this, a number of Westland Lysanders were procured at short notice from the RAF. 755 Squadron's remaining Sharks were replaced in October 1942 by Curtiss Seamews, an aircraft that proved to be less than successful.

757 Squadron went into a state of inactivity in August 1939, reforming in March 1941, flying Blackburn Skuas and a pair of Hawker Nimrods. The initial part of the gunnery course was given at Worthy Down before pupils moved to RNAS St Merryn in Cornwall for live firing training. Lysanders replaced 757's Skuas in April 1942 before the unit was absorbed by 755 Squadron on 1 December 1942.

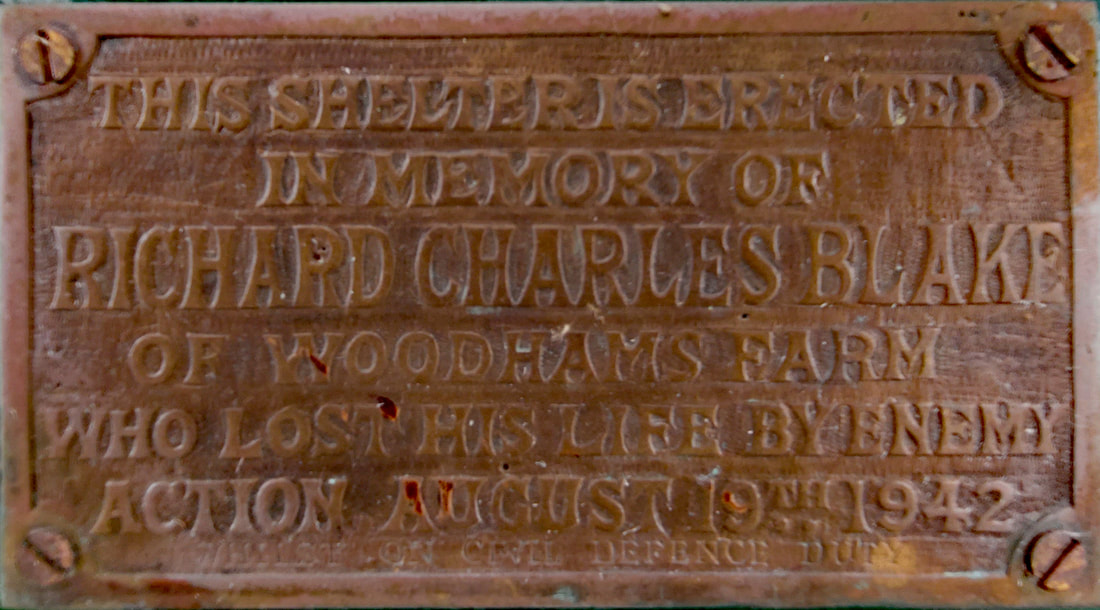

One who served with TAG School was a local man named William Henry Cundell Blake. He was brought up in nearby Woodhams Farm Kings Worthy. With a passion for flying, he obtained his pilot's licence from the Hampshire Flying School Hamble in 1929. After this, he decided to build his own aircraft, a feat he achieved by cobbling together parts from various machines, including the fuselage from a Simmonds Spartan, wings from an Avro 504K and a 35hp engine. Helped by his brother Richard, Billy completed his machine named the Blake Bluetit and flew it once around Kings Worthy. When war broke out, Billy joined the Fleet Air Arm and was posted to Worthy Down as a pilot with the School. He eventually became a Lieutenant Commander in the Royal Navy Volunteer Reserve (RNVR). He flew many types of aircraft that were at one time or another located at the airfield, including, interestingly, Boulton Paul Defiant, Blackburn Firebrand and Vickers Wellington. The Bluetit still exists to this day, with restoration continuing at a location in Herefordshire.

The TAG School activity continued with a number of changes taking place among the squadrons. Although 756 Squadron had been absorbed into 755 Squadron by August 1939, on 6 March 1941, 756 reformed in its own right as an advanced section of the school. The squadron flew Percival Proctor aircraft but was again absorbed by 755 on 1 December 1942.

By July 1941, a shortage of spares for 755 Squadron's elderly Shark aircraft was becoming apparent. To overcome this, a number of Westland Lysanders were procured at short notice from the RAF. 755 Squadron's remaining Sharks were replaced in October 1942 by Curtiss Seamews, an aircraft that proved to be less than successful.

757 Squadron went into a state of inactivity in August 1939, reforming in March 1941, flying Blackburn Skuas and a pair of Hawker Nimrods. The initial part of the gunnery course was given at Worthy Down before pupils moved to RNAS St Merryn in Cornwall for live firing training. Lysanders replaced 757's Skuas in April 1942 before the unit was absorbed by 755 Squadron on 1 December 1942.

One who served with TAG School was a local man named William Henry Cundell Blake. He was brought up in nearby Woodhams Farm Kings Worthy. With a passion for flying, he obtained his pilot's licence from the Hampshire Flying School Hamble in 1929. After this, he decided to build his own aircraft, a feat he achieved by cobbling together parts from various machines, including the fuselage from a Simmonds Spartan, wings from an Avro 504K and a 35hp engine. Helped by his brother Richard, Billy completed his machine named the Blake Bluetit and flew it once around Kings Worthy. When war broke out, Billy joined the Fleet Air Arm and was posted to Worthy Down as a pilot with the School. He eventually became a Lieutenant Commander in the Royal Navy Volunteer Reserve (RNVR). He flew many types of aircraft that were at one time or another located at the airfield, including, interestingly, Boulton Paul Defiant, Blackburn Firebrand and Vickers Wellington. The Bluetit still exists to this day, with restoration continuing at a location in Herefordshire.

|

Billy died in 1988 and is buried in the churchyard of St Mary's Kings Worthy. He is interred with his brother Richard, who died as a result of enemy action on 19 August 1942.

His loss is considered to be due to falling anti-aircraft fire shrapnel while on civil defence duty. Today a small memorial plate is located within a bus shelter in Springvale. |

Spitfire development continued at Worthy Down, with the maiden flight on 27 November 1941 of the first Rolls-Royce Griffon powered Spitfire IV, DP845. Also, much of the early development work on the Seafire was taking place at the field. With the activity of Supermarine and the arrival of more Percival Proctors in 1942 for the TAG School, the airfield became fairly crowded. Jeffrey Quill had a coming together with a Proctor while testing a Spitfire. The accident occurred on the ground with the Proctor being written off and the Spitfire badly damaged.

|

When researching for articles such as this, tales of human tragedy often come to the fore. A grave in the churchyard of St John the Baptist in the Hampshire village of Itchen Abbas is the final resting place of Lieutenant Anthony Douglas Brodie RNVR.

Lieutenant Brodie took off from Worthy Down in a Percival Proctor BV591 (similar to the photo left) on 7 July 1942. Near Abingdon, the aircraft broke up after part of the wing failed. He, along with two others in the aircraft, including a WREN, was killed. |

|

It is somewhat poignant to note on the gravestone (left) that Lieutenant Brodie's son, Peter, was also killed while flying from HMS Hermes on 3 January 1967.

Peter was Observer aboard De Havilland Sea Vixen FAW.2 XS588 when a bad approach to the carrier was waved off, resulting in a stalled engine. As a result, the aircraft crashed into the Mediterranean Sea off Malta, which led to the loss of Peter at the age of 26. When the TAG School at Yarmouth in Nova Scotia, Canada, was established, the units at Worthy Down were run down. Nos 756 and 757 Squadrons disbanded while 755 continued with the unpopular Curtiss Seamew, which they used until April 1944. |

Celebrity Status

|

An airfield in rural Hampshire was not a place you would expect to be touched by the glamour of Hollywood. However, two significant players in the world of film and stage flew from Worthy Down during its wartime years. At the beginning of 1940, Lawrence Olivier, by then a very successful Hollywood actor and his wife, Vivien Leigh, returned to the UK to assist the war effort. Initially wishing to join the RAF, Olivier was swayed to enlist with the Royal Navy Reserves. His fellow thespian Ralph Richardson was already serving in the Senior Service as a Sub Lieutenant.

|

Both Olivier and Richardson flew with the FAA at Worthy Down as Sub Lieutenants, with neither being classed as particularly gifted pilots. By his own admission Richardson, or 'Pranger', as he was nicknamed due to aircraft seeming to fall to pieces under his control, was a timid pilot. On the other hand, Olivier was known to be more reckless and often flouted the rules of the air. There are tales of him flying under bridges, low flypasts and even one of flying inverted with no warning, which left the aircraft's observer hanging on for dear life. Like Richardson, several of Olivier's aircraft met with untimely ends, but this did not deter the actor's love of flying and continuing to 'assist the war effort'.

With several years of service behind him, Olivier came under a different spotlight, this time one from Whitehall. Questions were asked about whether it was better for the war effort that Olivier's natural talent could be used elsewhere. In 1943 the Ministry of Information asked him to take the lead role in the film Henry V, which he subsequently directed and produced. Following on from Henry V, Olivier was asked to help re-establish the Old Vic Theatre. The company's governors approached the Royal Navy and asked if Olivier and Richardson could be released from service. A rapid response was received from the Navy, which led to Olivier stating that the Sea Lords agreed "with a speediness and lack of reluctance which was positively hurtful".

Olivier went on to play Sir Hugh Dowding in the 1968 film Battle of Britain. Richardson starred in the 1952 David Lean film the Sound Barrier, where he played wealthy aircraft factory owner John Ridgefield, some of which was filmed at nearby RAF Chilbolton. He also appeared in the epic 1968 film The Battle of Britain, where Richardson played Sir David Kelly, Britain's Ambassador to Switzerland.

With several years of service behind him, Olivier came under a different spotlight, this time one from Whitehall. Questions were asked about whether it was better for the war effort that Olivier's natural talent could be used elsewhere. In 1943 the Ministry of Information asked him to take the lead role in the film Henry V, which he subsequently directed and produced. Following on from Henry V, Olivier was asked to help re-establish the Old Vic Theatre. The company's governors approached the Royal Navy and asked if Olivier and Richardson could be released from service. A rapid response was received from the Navy, which led to Olivier stating that the Sea Lords agreed "with a speediness and lack of reluctance which was positively hurtful".

Olivier went on to play Sir Hugh Dowding in the 1968 film Battle of Britain. Richardson starred in the 1952 David Lean film the Sound Barrier, where he played wealthy aircraft factory owner John Ridgefield, some of which was filmed at nearby RAF Chilbolton. He also appeared in the epic 1968 film The Battle of Britain, where Richardson played Sir David Kelly, Britain's Ambassador to Switzerland.

A memory of a navigator/observers time flying with Olivier can be found here - Stephen Arthur de Mowbray's Memories

(I am indebted to Marcus de Mowbray for writing his fathers memories for use on this site)

(I am indebted to Marcus de Mowbray for writing his fathers memories for use on this site)

The War Progresses

|

Trials of the Mark XIV Spitfire started in November 1943, however, as the facilities at High Post improved, Supermarine development flying was transferred from Worthy Down in March 1944. The airfield now became home to some more unusual FAA units.

No 739 Squadron (Blind Approach Development Unit) moved in with Airspeed AS.10 Oxfords during September 1943. They were joined by 734 Squadron, which formed in February 1944, equipping with Armstrong Whitworth Whitley GR VIIIs. |

These pre-war designed bombers were used as flying classrooms to instruct TBR aircrew in the correct engine handling for those converting from biplanes to Rolls-Royce Merlin-powered Barracudas. Each aircraft was fitted out with instrumentation and fuel flow meters to give student pilots an understanding of throttle and boost settings. The unit remained at Worthy Down until August 1945, after which moving to Hinstock.

Worthy Down was not an airfield that was ideally suited for use by heavy bombers of the World War Two era with its undulating uneven ground. This, however, did not stop two Consolidated B-24H Liberator bombers from the US 8th Air Force from making a surprise emergency landing in June 1944. The two bombers 42-52682, 3R:H 'Wild Honey' and 42-52664, 3R:G 'Black Panther' of the 486th Bomb Group based at Station 174 Sudbury, landed at the airfield with full bomb loads. The photo below right shows 'Black Panther' having its ordnance removed by USAAF personnel, presumably to make the aircraft light enough to take off again.

Thanks go to Tony Dowland for allowing the use of the two photos shown below.

Worthy Down was not an airfield that was ideally suited for use by heavy bombers of the World War Two era with its undulating uneven ground. This, however, did not stop two Consolidated B-24H Liberator bombers from the US 8th Air Force from making a surprise emergency landing in June 1944. The two bombers 42-52682, 3R:H 'Wild Honey' and 42-52664, 3R:G 'Black Panther' of the 486th Bomb Group based at Station 174 Sudbury, landed at the airfield with full bomb loads. The photo below right shows 'Black Panther' having its ordnance removed by USAAF personnel, presumably to make the aircraft light enough to take off again.

Thanks go to Tony Dowland for allowing the use of the two photos shown below.

The School of Aircraft Maintenance (SAM) had come into existence in December 1942 at Lee-on-Solent to consolidate maintenance training and air mechanics courses. The School moved to Worthy Down in September 1944, with 739 NAS leaving for Donibristle in October 1944. Following this activity at the airfield slowly wound down. No 700 Maintenance Test Pilot's School moved in during November 1944, attaching themselves to the SAM. Their role was to carry out test flying on the basic aircraft types that were then in service, and they stayed until moving to Middle Wallop in November 1945.

|

Another addition seen during 1945 was the first helicopters in the form of the Sikorsky YR-4B and R-4B Hoverfly I, which came to be worked on by the Helicopter Servicing Flight before release back into service. Two Tiger Moths of the Southampton University Air Squadron remained on station until October 1946, after which they departed to Eastleigh. This effectively was the end of home-based flying at the airfield, but the aviation connection remained for many years, including an At Home airshow held on 23 June 1956.

|

|

In the 1950s, Worthy Down was in use as a ground target, and there is an eyewitness account from Tony Dowland of Hawker Sea Furies from the RNVR carrying out mock attacks. On Sunday afternoons, the air and surrounding countryside was filled with the sound of Bristol Centaurus engines. This annoyed many a local but not Tony, who enjoyed the sight and sound of this very iconic aircraft.

|

In the summer of 2011, a visit to Tangmere Aviation Museum provided more eye witness detail from one of the volunteers. He advised that he was stationed at Worthy Down and was responsible for the bombing range. He recounted that one day a Westland Wyvern was undertaking attacks on the range. While diving into the attack, the aircraft's canopy suddenly became detached and fluttered down to earth, luckily without causing damage to any of the nearby houses.

HMS Kestrel paid off in July 1952 but reopened shortly after as HMS Aerial. This was to house the Air Electrical School (AES), but no flying took place. In peacetime, the FAA continued to undertake training which inevitably led to accidents. There was a requirement to retrieve downed airframes from locations around the country and to cater for this Naval Aircraft Transport and Salvage Unit (NATSU) was formed post-war at Abbotsinch, Worthy Down, Stretton, Donibristle and Eglington. The entity based at Worthy was No 2 NATSU who changed its name to Southern Naval Aircraft Transport and Salvage Unit (SNATSU) in October 1955. It was not unusual to see stricken aircraft remains loaded aboard Queen Mary Trailers making their way through Winchester's local roads after being retrieved from far-flung locations. SNATSU was amalgamated into the Mobile Aircraft Repair, Transport and Salvage Unit formed at Lee-on-Solent in April 1959.

HMS Kestrel paid off in July 1952 but reopened shortly after as HMS Aerial. This was to house the Air Electrical School (AES), but no flying took place. In peacetime, the FAA continued to undertake training which inevitably led to accidents. There was a requirement to retrieve downed airframes from locations around the country and to cater for this Naval Aircraft Transport and Salvage Unit (NATSU) was formed post-war at Abbotsinch, Worthy Down, Stretton, Donibristle and Eglington. The entity based at Worthy was No 2 NATSU who changed its name to Southern Naval Aircraft Transport and Salvage Unit (SNATSU) in October 1955. It was not unusual to see stricken aircraft remains loaded aboard Queen Mary Trailers making their way through Winchester's local roads after being retrieved from far-flung locations. SNATSU was amalgamated into the Mobile Aircraft Repair, Transport and Salvage Unit formed at Lee-on-Solent in April 1959.

|

Flying had not entirely ceased at Worthy Down. In November 1959, 848 NAS re-equipped with 16 Westland Whirlwind HAS.7 helicopters. No 848 left the airfield in March 1960 to join the carrier HMS Bulwark and a voyage to warmer climes.

In November 1960, AES moved to Lee On Solent, and again, Worthy Down was paid off the following December. After this, the Royal Army Pay Corps took over the site. In 1992 the Pay Corps amalgamated with the Adjutants General Corps. |

Although flying ceased at the airfield many years ago, the RAF do sometimes still make an appearance. One such occasion was during April 2021 when Westland Puma HC.2 XW204 (from the Benson Wing based at RAF Benson) carried out a field landing near the camp perimeter.

|

Ground Defences

The ground defences at Worthy Down were fairly substantial and consisted of a number of pillboxes surrounding the airfield's perimeter. Today 25 pillboxes remain intact. There was three rare counter-balance type Picket Hamilton pillboxes located on the landing ground. Two of these survive, one being listed by English Heritage due to its rareness and type, but more on that subject later. |

|

Worthy Down Today

In June 2014, the Ministry of Defence announced £250 million would be invested at Worthy Down to create a Tri-service training establishment. Known as the Defence College of Logistics, Policing and Administration, the facility provides training in all logistic disciplines to the British Army, Royal Navy and Royal Air Force. At the time of writing (January 2021), the site construction has almost been completed, with practically all the former airfield buildings swept away. A new museum detailing the history of the Royal Logistics Corps has been opened near the main gate, details of which can be found by following this link: www.royallogisticcorps.co.uk |

What Remains Today

All Images - Richard Hall

Outside of the live base, remains from the former airfield can still be found. The landing ground is now turned over to agriculture. The perimeter tracks are used as a recreational facility by residents of nearby South Wonston, where a large housing estate has sprung up over the years.

The 1918 Officers Mess was demolished in 2020, information relating to this can be found here: www.airshowspresent.com

All Images - Richard Hall

Outside of the live base, remains from the former airfield can still be found. The landing ground is now turned over to agriculture. The perimeter tracks are used as a recreational facility by residents of nearby South Wonston, where a large housing estate has sprung up over the years.

The 1918 Officers Mess was demolished in 2020, information relating to this can be found here: www.airshowspresent.com

|

One of the first items that is noted when visiting the site is this Dutch Barn hangar which has somehow survived for many years. The Dutch Barn was very narrow as it would take naval aircraft with folding wings. Of note, the steelwork inside was manufactured by the Lanarkshire Steel Co Ltd Scotland.

|

|

Located out on the landing ground is this rare counterbalance type Pickett Hamilton (PH) Pillbox. The box is pretty much complete. I have ventured inside but it is rather wet underfoot. This structure is listed due to its rarity. A further PH survives but is not internally accessible at present. If you intend to visit this area of the airfield at anytime it is best to wait until after harvest, least the farmer gets upset.

|

|

During the build up to D-Day the railway that ran near the camp was upgraded to enable the passage of troops and war materials from the Industrial North. A new platform was constructed and upon it was placed this building which was known as the Admiralty Store. It would appear that the railway was used to transport aero engines as a purpose built crane was constructed next to the line to aid lifting and loading. During the war a leave train ran most nights at the request of the Royal Navy.

|

It became well known due to the antics of drunken sailors returning from a beer up in Winchester. In the end the RN had to put Officers on board the train to keep order, if the sailors left a mess in the train then they had to clear it up. This often meant them returning back to Winchester as the train returned empty stock. A four mile walk then ensued back to Worthy Down which must have acted as a future deterrent to cause trouble.

|

To the east of the camp lies the sewerage disposal works. The drainage system serving the works has a number of manholes that are still very evident today. Each of the manholes has one of these cast iron covers in place. All are marked with the Air Ministry stamp which gives a reminder of Worthy Down's past as an active airfield.

|

One aircraft that was based at Worthy Down was Fairey Swordfish II LS326. This aircraft was at the airfield after the end of its active service life and was used for training and communication. LS326 now resides at RNAS Yeovilton as part of the Fly Navy Heritage Trust, formerly the Royal Navy Historic Flight.

100 Years Anniversary

On 29 June 2017, an event was held at former RAF/RNAS Worthy Down to commemorate the 100th anniversary of the airfield's opening in 1917. In attendance on the day were Westland Sioux AH.1 XT131 and Westland Scout AH.1 XT626, from the Historic Army Aircraft Flight.

A Personal View

So that concludes the look at the history and the present-day Worthy Down. It is a site with a rich history, but today has quietly gone back to an agricultural existence. I often visit the field and try and visualise the aircraft on approach. I think of Harris, who flew from the field and then became a controversial figure in the RAF due to his strategy of area bombing. It was always a wish I could hear a Merlin on full song as the engine struggles uphill to lift the Spitfire into her natural element, the air, at Worthy Down.

I almost got my wish in 2010. With the celebrations surrounding the 70th anniversary of the Battle of Britain, a flypast was arranged for the BBMF Lancaster to fly over former airfields used in the Battle. The day was set, time was taken off from work. I took my powerful 500mm lens and camera to stand in the middle of the former landing ground. A large crowd of people gathered to witness the event. However, as always, the English weather intervened and kept the Lancaster firmly on the ground at Bournemouth.

So I never did get to hear the Merlin over Worthy Down, and I never took the shot that was likely to me to be a once in a lifetime event. Oh well, sometimes such things are best left to the imagination

I almost got my wish in 2010. With the celebrations surrounding the 70th anniversary of the Battle of Britain, a flypast was arranged for the BBMF Lancaster to fly over former airfields used in the Battle. The day was set, time was taken off from work. I took my powerful 500mm lens and camera to stand in the middle of the former landing ground. A large crowd of people gathered to witness the event. However, as always, the English weather intervened and kept the Lancaster firmly on the ground at Bournemouth.

So I never did get to hear the Merlin over Worthy Down, and I never took the shot that was likely to me to be a once in a lifetime event. Oh well, sometimes such things are best left to the imagination

A View From The Past

Walking over the former airfield at Worthy Down a couple of days after Christmas 2016 evoked the usual minds-eye image of times long past. Then, Worthy Down was a flight test site for Spitfires delivered from local dispersed construction factories such as Chattis Hill or High Post. The aircraft were put through their paces at the airfield before the onward flight to front line squadrons.

As I looked down the former approach in my mind, I could see a Spitfire lining up to land from a curved approach, possibly with Jeffrey Quill at the controls, as he was once a test pilot here. So I decided to recreate that image below to show what was once a reality.

As I looked down the former approach in my mind, I could see a Spitfire lining up to land from a curved approach, possibly with Jeffrey Quill at the controls, as he was once a test pilot here. So I decided to recreate that image below to show what was once a reality.

Sources

Action Stations 9 - Chris Ashworth

Bomber Harris - Dudley Saward

The Flowerdown Link 1918-1978 - Squadron Leader L L R Burch

Military Airfields In The British Isles 1939 - 1945 - Steve Willis & Barry Holliss

The Didcot Newbury and Southampton Railway - Paul Karau - Mike Parsons & Kevin Robertson

Fleet Air Arm Helicopters Since 1943 - Lee Howard - Mick Burrow - Eric Myall - Air Britain

The Squadrons And Units Of The Fleet Air Arm - Theo Ballance - Lee Howard - Ray Sturtivant - Air Britain

Flying Training And Support Units since 1912 - Ray Sturtivant - Air Britain

Forgotten Airfields of World War 1 - Martyn Chorlton - Crecy

Eugene Esmonde VC DSO - Chaz Bowyer - William Kimber

The Most Dangerous Enemy - Stephen Bungay - Aurum Press Ltd

hostmaster.greyhoundderby.com

The Hampshire Chronicle

Dave Smith

Richard Sacree

Tony Dowland

Neville Cullingford

Tony Weekes

Sean McRandle

Richard Flagg

Paul Bellamy

daveg4otu.tripod.com

Action Stations 9 - Chris Ashworth

Bomber Harris - Dudley Saward

The Flowerdown Link 1918-1978 - Squadron Leader L L R Burch

Military Airfields In The British Isles 1939 - 1945 - Steve Willis & Barry Holliss

The Didcot Newbury and Southampton Railway - Paul Karau - Mike Parsons & Kevin Robertson

Fleet Air Arm Helicopters Since 1943 - Lee Howard - Mick Burrow - Eric Myall - Air Britain

The Squadrons And Units Of The Fleet Air Arm - Theo Ballance - Lee Howard - Ray Sturtivant - Air Britain

Flying Training And Support Units since 1912 - Ray Sturtivant - Air Britain

Forgotten Airfields of World War 1 - Martyn Chorlton - Crecy

Eugene Esmonde VC DSO - Chaz Bowyer - William Kimber

The Most Dangerous Enemy - Stephen Bungay - Aurum Press Ltd

hostmaster.greyhoundderby.com

The Hampshire Chronicle

Dave Smith

Richard Sacree

Tony Dowland

Neville Cullingford

Tony Weekes

Sean McRandle

Richard Flagg

Paul Bellamy

daveg4otu.tripod.com