RAF Odiham

From Biplanes to Helicopters

Written by Richard Hall

Airfield Code Letters - OI

It was a warm summer day as a group of men worked the fields in the rolling hills of the Hampshire landscape. This was thirsty work under a blazing sun, and it was time for a breather and a well-earned beverage as in the blue yonder, the Skylarks sang out their incessant song. As they lay down on the dusty ground, the men's senses were assailed by the sound of aero engines and, in the distance, a flight of single-engine bi-planes slowly appeared and set up their pattern to land at Downs Farm Odiham. As the men watched, they could see the goggles and leather flying helmets of the pilots and observers, some of the latter giving a cheery, friendly wave as they passed overhead with the engine exhausts crackling upon the cut of the throttle to a gentle flair and a bumpy landing across the rough grass. The idyllic scene the men observed was not new to them as in previous years, the Royal Air Force (RAF) had often sent some of its squadrons to the temporary airfield on Summer Camps.

In the early 1920s, memories of the First World War, in which millions of lives were lost on all sides, were still uppermost in the minds of the military and public alike. There was little appetite to increase air assets, or any other military means for that matter. The RAF continued to fly aircraft that were a throwback to the earlier years of military aviation. If the Army and Royal Navy had had their way post-war, the service would have been liquidated, and it was only the efforts of the Chief of Air Staff, Air Vice Marshal (later Marshal of the RAF) Sir Hugh Trenchard, that saved it. Therefore, the man known as the 'Father of the Royal Air Force' nurtured his small force even if the aircraft it was flying had seen better days. He knew the importance of air power, and in time, his vision would be realised.

The RAF's strength following the end of the war was reduced by around 90%. In 1922, the War Office was concerned that France had an air force that was double the size of the home nation. Although there was little likelihood of war with the cross-Channel neighbour, the difference in strength did not sit well, and it was decided parity should be achieved, which led to an increase in the RAF's squadrons. During the war, aircraft went from being considered as a bit of a novelty with no real use to a potent weapon and game-changer. From their lofty heights over the battlefield, aircrews could direct artillery fire, reconnoitre and, of course, bomb, strafe and dogfight. However, it was recognised that aircraft needed to communicate effectively with those on the ground. Through the use of radiotelegraphy, the days of army cooperation squadrons came into being.

It was a warm summer day as a group of men worked the fields in the rolling hills of the Hampshire landscape. This was thirsty work under a blazing sun, and it was time for a breather and a well-earned beverage as in the blue yonder, the Skylarks sang out their incessant song. As they lay down on the dusty ground, the men's senses were assailed by the sound of aero engines and, in the distance, a flight of single-engine bi-planes slowly appeared and set up their pattern to land at Downs Farm Odiham. As the men watched, they could see the goggles and leather flying helmets of the pilots and observers, some of the latter giving a cheery, friendly wave as they passed overhead with the engine exhausts crackling upon the cut of the throttle to a gentle flair and a bumpy landing across the rough grass. The idyllic scene the men observed was not new to them as in previous years, the Royal Air Force (RAF) had often sent some of its squadrons to the temporary airfield on Summer Camps.

In the early 1920s, memories of the First World War, in which millions of lives were lost on all sides, were still uppermost in the minds of the military and public alike. There was little appetite to increase air assets, or any other military means for that matter. The RAF continued to fly aircraft that were a throwback to the earlier years of military aviation. If the Army and Royal Navy had had their way post-war, the service would have been liquidated, and it was only the efforts of the Chief of Air Staff, Air Vice Marshal (later Marshal of the RAF) Sir Hugh Trenchard, that saved it. Therefore, the man known as the 'Father of the Royal Air Force' nurtured his small force even if the aircraft it was flying had seen better days. He knew the importance of air power, and in time, his vision would be realised.

The RAF's strength following the end of the war was reduced by around 90%. In 1922, the War Office was concerned that France had an air force that was double the size of the home nation. Although there was little likelihood of war with the cross-Channel neighbour, the difference in strength did not sit well, and it was decided parity should be achieved, which led to an increase in the RAF's squadrons. During the war, aircraft went from being considered as a bit of a novelty with no real use to a potent weapon and game-changer. From their lofty heights over the battlefield, aircrews could direct artillery fire, reconnoitre and, of course, bomb, strafe and dogfight. However, it was recognised that aircraft needed to communicate effectively with those on the ground. Through the use of radiotelegraphy, the days of army cooperation squadrons came into being.

|

On 1 April 1924, No. 13 Squadron reformed at Kenley in the role of army cooperation, equipped with the Bristol F.2B Fighter, an aircraft whose roots were firmly established in the First World War and a product of a lack of investment in the RAF's equipment. The unit's primary task was to develop techniques for providing direct air support to front-line troops. In June of the same year, the unit moved to Andover and was shortly after tasked to photograph sites in the surrounding area that could potentially be used as exercise landing grounds.

|

One promising field was identified at Downs Farm, a mile south of Odiham. The location was considered suitable due to the close proximity of Aldershot and Salisbury Plain, areas of military training activity. In due course, the Air Ministry purchased the land with a plan to use it as a site to hold Summer Camps. In September 1929, the unit moved to Netheravon on Salisbury Plain.

Over the coming years, Nos. 4 and 13 Squadrons would become regular visitors at Downs Farm. The accommodation at the site was very basic, with Bessoneau canvas hangars provided for the F.2Bs and tents for the human contingent, which, in all likelihood, wouldn't have been too bad given the area's use being confined to the summer months.

It is probable the first use of the field came in 1925/26, but there is a lack of evidence within the National Archive for either Nos. 4 and 13 Squadrons to substantiate this as the available Operations Record Books (ORB) start in July 1930 and October 1926 respectively. As both units formed well before these dates, the relevant ORBs may have gone missing or have been misplaced. The first entry within No. 13 Squadron's ORB mentioning Odiham comes between 21 June and 30 July 1927 under the command of Sqn Ldr D. R. A. Deacon when it used Downs Farm as an advanced landing ground during Brigade Training with the First Division Aldershot. The squadron's ORB gives further instances of the use of the landing ground from where exercises were conducted; some of the more notable are shown below:

Over the coming years, Nos. 4 and 13 Squadrons would become regular visitors at Downs Farm. The accommodation at the site was very basic, with Bessoneau canvas hangars provided for the F.2Bs and tents for the human contingent, which, in all likelihood, wouldn't have been too bad given the area's use being confined to the summer months.

It is probable the first use of the field came in 1925/26, but there is a lack of evidence within the National Archive for either Nos. 4 and 13 Squadrons to substantiate this as the available Operations Record Books (ORB) start in July 1930 and October 1926 respectively. As both units formed well before these dates, the relevant ORBs may have gone missing or have been misplaced. The first entry within No. 13 Squadron's ORB mentioning Odiham comes between 21 June and 30 July 1927 under the command of Sqn Ldr D. R. A. Deacon when it used Downs Farm as an advanced landing ground during Brigade Training with the First Division Aldershot. The squadron's ORB gives further instances of the use of the landing ground from where exercises were conducted; some of the more notable are shown below:

- July 1928: Squadron provided army cooperation for 1st Divisional Battalion and Brigade Training at Aldershot.

- August 1928: Squadron provided army cooperation for Territorial units at Aldershot, Worthing, Shorncliffe and Bordon.

- 19 April 1929: Squadron moved from Sutton Bridge to Odiham for Summer Camp.

- 19 May 1930: Squadron moved to Odiham at full war strength and with full mobilisation. [The deployment would last until September of the same year, after which the unit moved back to Netheravon].

- 18 May 1931: Moves to Odiham for Summer Camp.

- 4 July 1932: B Flight moved to Odiham for Staff College Signals exercise.

- 23 May 1933: Squadron moved to Odiham for Air Ministry and War Office exercise. Returned [to Netheravon] 19 June 1933.

- 24 July 1933: Squadron moved to Odiham for Brigade and Divisional exercises. (This appears to be the last use of the field by No. 13 Squadron). Returned [to Netheravon] 26 August 1933].

|

The above is a snapshot of the unit's activities, and there are more instances of it using Downs Farm up until July 1933. During this time, conversion to the Armstrong Whitworth Atlas I came in August 1927, followed by the Hawker Audax I in February 1932. While at Downs Farm, it was common practice for the squadron in part or as a whole to detach to other locations, such as Sutton Bridge (RAF Practice Camp) and Okehampton (Royal Artillery Practice Camp), for up to a month at a time before returning. The stay at the landing ground varied, and there was no consistent period of time of occupation and varied upon need and prevailing requirements.

|

The first evidence of No. 4 Squadron using the landing ground comes from the ORB on 10 July 1930 under the command of Sqn Ldr N. H. Bottomley for a Second Division Signals exercise. On the day, further cooperation duties took place with the 5th and 6th Infantry Brigades. This appears to be the only recorded instance of it using the field in 1930. The following deployment is also noted:

This is where the trail ends for No. 4 Squadron, and there are no further instances of it using Downs Farm noted in the ORB. As previously stated, the period between the formation of the unit and 1930 is missing from the records, but in all likelihood, it used the field during the preceding years.

As the days of the late 1920s to mid-1930s progressed, the threat of war was once again hanging over Europe due to the rise of the National Socialist German Workers Party (Nazi) in Germany. Therefore, locations for airfield expansion were being sought in Britain. As the site of Down Farm had previously proven successful for Summer Camps, it lent itself to being considered for the location of a permanent airfield. In 1934 work began at Odiham to construct an Expansion Period airfield. Construction commenced of three C type hangars, accommodation blocks and various buildings that were to be typically found on such a site. The airfield was built by contractor Lindsay Parkinson Ltd and handed over to the RAF in December 1936, with allocation to No. 22 Group upon completion.

- 25 to 27 June 1931: Nos. 4 and 13 (AC) Squadron took part in Staff College Signal exercise operating from Odiham (this ties in with No. 13's deployment to the field from 18 May 1931 to 8 August of the same year).

This is where the trail ends for No. 4 Squadron, and there are no further instances of it using Downs Farm noted in the ORB. As previously stated, the period between the formation of the unit and 1930 is missing from the records, but in all likelihood, it used the field during the preceding years.

As the days of the late 1920s to mid-1930s progressed, the threat of war was once again hanging over Europe due to the rise of the National Socialist German Workers Party (Nazi) in Germany. Therefore, locations for airfield expansion were being sought in Britain. As the site of Down Farm had previously proven successful for Summer Camps, it lent itself to being considered for the location of a permanent airfield. In 1934 work began at Odiham to construct an Expansion Period airfield. Construction commenced of three C type hangars, accommodation blocks and various buildings that were to be typically found on such a site. The airfield was built by contractor Lindsay Parkinson Ltd and handed over to the RAF in December 1936, with allocation to No. 22 Group upon completion.

|

Given its proximity to London, Odiham was a firm favourite to attract visitors. Ironically the then Secretary-General of the Luftwaffe, Erhard Milch, conducted the official opening of the new RAF station on 18 October 1937. To think in just under three years, the Luftwaffe would be again visiting the airfield, but certainly not with the hand of friendship extended.

Milch oversaw the development of the Luftwaffe during the Nazi rearmament programme in the 1930s and aircraft production during World War Two. |

A lack of a clear strategy and a strong command structure, ultimately overseen by Milch, contributed to the many mistakes made concerning the Luftwaffe during the war years. This led to a weakening of the Luftwaffe as the war progressed, to its eventual collapse in the face of the massive Allied onslaught. Milch was convicted of war crimes at the Nuremberg Trials and was imprisoned for life, commuted to 15 years, with release coming in 1954, a year after the Royal Review held at RAF Odiham (more on this later).

The Whitley Experiment

|

Foresight on the part of some could see grass airfields would be of minimal use with the advent of heavy four-engine bomber aircraft currently in the design stage but would be procured and coming into service in future years.

To establish how these aircraft would fare with grass runways, an interesting experiment was undertaken at Odiham within its first year. |

Armstrong Whitworth Whitley prototype K4586 flew to the airfield from RAE Farnborough with a massive steel beam fitted between the main wheels, which had also been adapted with oversize Dunlop tyres. This gave the aircraft a weight of 18 tons, and soon it was carving deep furrows in the turf, but tests on other parts of the field showed less destructive results. To this end, rather foolishly, it was concluded heavy bombers could take off from grass, although not much thought had been given to what happens when it rains and the ground becomes soft.

The experiment allowed the treasury to conclude that expensive concrete runways were not required and the money could be saved for another day. Thankfully by 1939, airfields were being built with hard runways, which was just as well given the size and weight of the aircraft that would be using them in the not too distant future.

The experiment allowed the treasury to conclude that expensive concrete runways were not required and the money could be saved for another day. Thankfully by 1939, airfields were being built with hard runways, which was just as well given the size and weight of the aircraft that would be using them in the not too distant future.

Army Co-operation

|

The original purpose for Odiham was to house three Army Co-operation Squadrons, two of which Nos. 4 and 13. Flying the Hawker Audax, a variant of the Hawker Hart light bomber had arrived with No. 50 (AC) Wing in February 1937, with a third, No. 53 Squadron, equipped with Hawker Hectors, arriving later in the year. The three squadrons were soon active in their army cooperation role and took part in a range of training operations with ground forces.

|

Nos. 4 and 13 Squadrons soon converted to the Hawker Hector, again a derivative of the Hart, powered by an unusually configured 24 cylinder air-cooled Napier Dagger engine.

War Clouds Gather

As the decade moved towards its close, the war clouds were clearly gathering, and there was a haste to update the RAF's aircraft and equipment. The aircraft flown by Odiham's squadrons were outdated and would be no match for the modern fighters equipping the upcoming adversary, the Luftwaffe. Unfortunately, the machines that were to re-equip the squadrons would also struggle to take on a future enemy, but this was to be a lesson hard learnt later during the Battle of France.

Before the war began, Nos. 4 and 13 Squadrons re-equipped with the Westland Lysander, a single-engined army cooperation aircraft and No. 53 Squadron with Bristol Blenheim twin-engine light bombers. The year 1939 saw Odiham's grass runways give way to concrete, which was fortunate with the arrival of the heavier Blenheim aircraft.

War Clouds Gather

As the decade moved towards its close, the war clouds were clearly gathering, and there was a haste to update the RAF's aircraft and equipment. The aircraft flown by Odiham's squadrons were outdated and would be no match for the modern fighters equipping the upcoming adversary, the Luftwaffe. Unfortunately, the machines that were to re-equip the squadrons would also struggle to take on a future enemy, but this was to be a lesson hard learnt later during the Battle of France.

Before the war began, Nos. 4 and 13 Squadrons re-equipped with the Westland Lysander, a single-engined army cooperation aircraft and No. 53 Squadron with Bristol Blenheim twin-engine light bombers. The year 1939 saw Odiham's grass runways give way to concrete, which was fortunate with the arrival of the heavier Blenheim aircraft.

After war was declared on 3 September 1939, Odiham's Lysanders and Blenheims moved to France as part of the Air Component of the British Expeditionary Force (BEF). The period from September 1939 to April 1940 became known as the Phoney War due to relative inactivity, but in very short order, the war would take a very much more serious path.

The Home Front

|

After Nos. 4, 13 and 53 left for France, two Auxiliary squadrons, Nos. 613 (City of Manchester) and 614 (City of Glamorgan), flew their aircraft to Odiham, arriving on 2 October 1939. The two squadrons at this time were flying Hawker Hind, Hector and Westland Lysanders.

On the 3 October, B Flight of No. 614 Squadron was redesignated No. 614A becoming No. 225 Squadron, eight days later. The unit was tasked to aid local searchlight and anti-aircraft sites and undertake patrols along the Hampshire coast, including the Isle of Wight, which led to participation in air-sea rescue work. |

Blitzkrieg

The relative calm on the Western Front was shattered on 10 May 1940, when the Germans launched Blitzkrieg (Lightning War), with the Netherlands, Belgium and France quickly overrun. The Allied forces had never seen such tactics used in an attack before, which relied on close cooperation between air and ground forces and the effective by-passing of defensive positions, including the Maginot Line. Despite a gallant defence, the BEF and elements of the French army were driven back to the coast and the beaches of Dunkirk. Under constant aerial attack, over 300,000 troops were evacuated to Britain, many aboard 'Little Ships', requisitioned civilian vessels of all manner of sizes and types. This incredible feat was named Operation Dynamo. The BEF left most of its equipment behind in France during the evacuation, but this could be replaced. If the troops had been left in the country, Britain, already in a dangerous defensive position, in all likelihood would have to have sued for peace, and the destiny of Europe would have been very different.

One aircraft that really shouldn’t have flown into the hostile skies over Dunkirk were the Army Co-operation Hawker Hectors of 1 Flight, No. 613 Squadron. However, as a measure of how desperate the situation was, six Hectors flew from Odiham to Hawkinge before dawn on 26 May 1940. The squadron ORB describes how armed with two 120Ib general purpose bombs the half dozen antiquated biplanes took off at 09.50 hours and headed towards Calais where they carried out dive bombing attacks, surprisingly they all returned safely. The next day the squadron was again in action with their Hectors and Lysanders and also in cooperation with Fleet Air Arm Swordfish. This time they weren’t so lucky losing one of their number, Hector K8116 ZR-X to anti-aircraft fire. The machine made it back to Britain but crashed near Dover with the loss of gunner LAC Brown and with injuries sustained by Plt Off. Reg Jenkyns. This was to be the last time the unit, probably much to the relief of the crews, was to be called upon to participate in the evacuation.

During June 1940, Nos. 225, 613, and 614 Squadrons left Odiham for Old Sarum, Netherthorpe and Grangemouth, respectively. After the Fall of France, No. 59 Squadron flew their Bristol Blenheims via a somewhat roundabout route to Odiham, bringing with them tales of heroism and gallantry that were readily apparent in the fallen country. No. 59 stayed at Odiham for three weeks, at which time they busied themselves bombing enemy-held ports in France. Also arriving at the airfield from Old Sarum was No. 110 Squadron RCAF, City of Toronto, equipped with Lysanders. The squadron was soon busy training with local army units. One of their Lysanders was fitted experimentally with a 20mm cannon, the recoil from which must have had an interesting effect on the aircraft.

With the withdrawal from France, Britain stood alone to face the inevitable onslaught from the Germans, which was to become known as the Battle of Britain. There was a heightened alarm that Britain was soon to be invaded, and Hitler had plans to do just that with an operation known as Sea Lion. The rout in France severely weakened Britain's defences, and as such desperate measures were required to defend against any enemy invasion. One such was the use of aircraft such as Lysanders, Tiger Moths, or basically anything that could fly that could be adapted to drop bombs, being used to repel potential invaders. This was known as Operation Banquet and would have been a suicide mission for anyone involved, thankfully the operation never came to pass, and the RAF prevailed in the Battle of Britain.

In all likelihood, anything that could fly from Odiham would have been used to protect Britain's sovereignty had Operation Sea Lion been implemented in desperate last-ditch actions. It's a thought that doesn't bear thinking about as losses would have been severe among the seriously outmoded aircraft.

The relative calm on the Western Front was shattered on 10 May 1940, when the Germans launched Blitzkrieg (Lightning War), with the Netherlands, Belgium and France quickly overrun. The Allied forces had never seen such tactics used in an attack before, which relied on close cooperation between air and ground forces and the effective by-passing of defensive positions, including the Maginot Line. Despite a gallant defence, the BEF and elements of the French army were driven back to the coast and the beaches of Dunkirk. Under constant aerial attack, over 300,000 troops were evacuated to Britain, many aboard 'Little Ships', requisitioned civilian vessels of all manner of sizes and types. This incredible feat was named Operation Dynamo. The BEF left most of its equipment behind in France during the evacuation, but this could be replaced. If the troops had been left in the country, Britain, already in a dangerous defensive position, in all likelihood would have to have sued for peace, and the destiny of Europe would have been very different.

One aircraft that really shouldn’t have flown into the hostile skies over Dunkirk were the Army Co-operation Hawker Hectors of 1 Flight, No. 613 Squadron. However, as a measure of how desperate the situation was, six Hectors flew from Odiham to Hawkinge before dawn on 26 May 1940. The squadron ORB describes how armed with two 120Ib general purpose bombs the half dozen antiquated biplanes took off at 09.50 hours and headed towards Calais where they carried out dive bombing attacks, surprisingly they all returned safely. The next day the squadron was again in action with their Hectors and Lysanders and also in cooperation with Fleet Air Arm Swordfish. This time they weren’t so lucky losing one of their number, Hector K8116 ZR-X to anti-aircraft fire. The machine made it back to Britain but crashed near Dover with the loss of gunner LAC Brown and with injuries sustained by Plt Off. Reg Jenkyns. This was to be the last time the unit, probably much to the relief of the crews, was to be called upon to participate in the evacuation.

During June 1940, Nos. 225, 613, and 614 Squadrons left Odiham for Old Sarum, Netherthorpe and Grangemouth, respectively. After the Fall of France, No. 59 Squadron flew their Bristol Blenheims via a somewhat roundabout route to Odiham, bringing with them tales of heroism and gallantry that were readily apparent in the fallen country. No. 59 stayed at Odiham for three weeks, at which time they busied themselves bombing enemy-held ports in France. Also arriving at the airfield from Old Sarum was No. 110 Squadron RCAF, City of Toronto, equipped with Lysanders. The squadron was soon busy training with local army units. One of their Lysanders was fitted experimentally with a 20mm cannon, the recoil from which must have had an interesting effect on the aircraft.

With the withdrawal from France, Britain stood alone to face the inevitable onslaught from the Germans, which was to become known as the Battle of Britain. There was a heightened alarm that Britain was soon to be invaded, and Hitler had plans to do just that with an operation known as Sea Lion. The rout in France severely weakened Britain's defences, and as such desperate measures were required to defend against any enemy invasion. One such was the use of aircraft such as Lysanders, Tiger Moths, or basically anything that could fly that could be adapted to drop bombs, being used to repel potential invaders. This was known as Operation Banquet and would have been a suicide mission for anyone involved, thankfully the operation never came to pass, and the RAF prevailed in the Battle of Britain.

In all likelihood, anything that could fly from Odiham would have been used to protect Britain's sovereignty had Operation Sea Lion been implemented in desperate last-ditch actions. It's a thought that doesn't bear thinking about as losses would have been severe among the seriously outmoded aircraft.

A Friendly Invasion

With the downfall of much of mainland Europe, many former Belgium, French, Dutch and other National pilots made their way to Britain to continue the war against the Nazi invaders. To facilitate acceptance into RAF service, 1 Fighter Training School was formed at Odiham for Free French pilot training on 30 July 1940. A number of French aircraft that had escaped the German advance and had made it to Odiham were used for training. These included Farmar 222, Cauldron Goelands, Potez 63/11, Block 151 and Dewoitine 520s. In November 1940, the Fighter Training School became the Franco-Belgium Flying Training School and used Miles Magisters, Blenheims and Lysanders until June 1941, when the School disbanded.

An interesting account relating to the flight to Britain of No. 838, as pictured above written by Lawrence Hayward Air Britain Historians Member, can be read by following this link: Escape To Britain in a Potez 63/11

The Battle of Britain

Southern England during the summer of 1940 was a location of concern, anxiety and a place where the church bells didn't ring unless it was to signal an invasion. Personnel at Odiham would have seen overhead their airfield contrails and smoke trails from the numerous dogfights that took place during those momentous summer months.

One man who must take full credit for the RAF being able to mount a strong defence against the upcoming Luftwaffe onslaught was Air Chief Marshall Sir Hugh Dowding, Commanding Officer of Fighter Command. He had been instrumental in stopping his fighter squadrons from being wasted in the Battle of France. Furthermore, Dowding refused to continue to send reinforcements to the Continent even when requested by Churchill. He knew the battle was lost, and the fighters would be needed for home defence. This decision, to all intents and purposes, saved Britain.

To strike a decisive blow against the RAF, Hitler ordered Adlerangriff (Operation Eagle Attack), the purpose being for the Luftwaffe to gain air superiority over southern England, which would be required if any potential invasion was to be a success. The day the attack was planned, 13 August 1940, known as Adler Tag (Eagle Day), was chosen thanks to a ridge of high pressure over Britain at the time, which indicated favourable weather. However, the vagaries of mother nature intervened, and the weather on the morning of the attack dictated it be postponed until later in the day. Unfortunately, the Dornier Do 17Z crews of KG2s, II and III Gruppe led by Oberst Johannes Fink did not hear the stand-down message, something to do with the wrong radio crystals being fitted. As a result, they took off to commence their raids against southern England, with very little in the way of fighter protection. The escorting Messerschmitt Bf 110s of ZG26 led by the one-legged First World War veteran pilot Oberstleutnant Joachim Huth did hear the recall and tried to warn the bombers but radio communication was not possible due to the fighters being tuned to different frequency to the bombers. Huth resorted to flying in a wild way in front of them, but the bomber pilots considered the antics to be just high spirits and were soon left to their own devices by the escorts. The Luftwaffe raids were planned to destroy radar installations and RAF airfields, although some of the targets chosen were of dubious value due to inaccurate Luftwaffe intelligence. On the list over the coming days were Worthy Down (Fleet Air Arm), Eastchurch, Detling (Coastal Command), Odiham (Army Co-operation) and Upavon (Training), none of which were operated by Fighter Command, attacks on which would do little to help with gaining air superiority. Despite the lack of escort, the bombers continued and dropped ordnance over Eastchurch airfield, Leysdown and the Isle of Sheppey, but were intercepted by Nos. 74, 111 and 151 Squadron who shot down five Dorniers and damaged six more.

One man who must take full credit for the RAF being able to mount a strong defence against the upcoming Luftwaffe onslaught was Air Chief Marshall Sir Hugh Dowding, Commanding Officer of Fighter Command. He had been instrumental in stopping his fighter squadrons from being wasted in the Battle of France. Furthermore, Dowding refused to continue to send reinforcements to the Continent even when requested by Churchill. He knew the battle was lost, and the fighters would be needed for home defence. This decision, to all intents and purposes, saved Britain.

To strike a decisive blow against the RAF, Hitler ordered Adlerangriff (Operation Eagle Attack), the purpose being for the Luftwaffe to gain air superiority over southern England, which would be required if any potential invasion was to be a success. The day the attack was planned, 13 August 1940, known as Adler Tag (Eagle Day), was chosen thanks to a ridge of high pressure over Britain at the time, which indicated favourable weather. However, the vagaries of mother nature intervened, and the weather on the morning of the attack dictated it be postponed until later in the day. Unfortunately, the Dornier Do 17Z crews of KG2s, II and III Gruppe led by Oberst Johannes Fink did not hear the stand-down message, something to do with the wrong radio crystals being fitted. As a result, they took off to commence their raids against southern England, with very little in the way of fighter protection. The escorting Messerschmitt Bf 110s of ZG26 led by the one-legged First World War veteran pilot Oberstleutnant Joachim Huth did hear the recall and tried to warn the bombers but radio communication was not possible due to the fighters being tuned to different frequency to the bombers. Huth resorted to flying in a wild way in front of them, but the bomber pilots considered the antics to be just high spirits and were soon left to their own devices by the escorts. The Luftwaffe raids were planned to destroy radar installations and RAF airfields, although some of the targets chosen were of dubious value due to inaccurate Luftwaffe intelligence. On the list over the coming days were Worthy Down (Fleet Air Arm), Eastchurch, Detling (Coastal Command), Odiham (Army Co-operation) and Upavon (Training), none of which were operated by Fighter Command, attacks on which would do little to help with gaining air superiority. Despite the lack of escort, the bombers continued and dropped ordnance over Eastchurch airfield, Leysdown and the Isle of Sheppey, but were intercepted by Nos. 74, 111 and 151 Squadron who shot down five Dorniers and damaged six more.

|

Also not hearing the recall were the Ju 88A-1s of I and II/KG54, who had also taken off and headed towards the south coast. Twenty bombers from I/KG54 were briefed to attack RAE Farnborough while eighteen from II/KG54 were sent to Odiham. Neither raid reached their targets thanks to the efforts of Nos. 43, 64, 87, 238, 257 and 601 Squadrons. The bombers without effective fighter escort were hampered by the cloud conditions and became increasingly frustrated by the attentions of RAF fighters. Venturing no more than 10 miles inland, the order was given for the bombers to turn back and therefore, on this occasion, Odiham was spared.

|

As the weather improved the Luftwaffe continued to launch attacks throughout the day, and once the hostile plots had dried up from Dowding's Group operations tables, the Luftwaffe had lost 47 aircraft and the RAF 13, three of whose pilots had been killed. During the day, six airfields were attacked, with 47 aircraft destroyed, only one of which was a fighter.

On 15 August 1940, large scale attacks were made by Luftflotte 5 based in Norway and Denmark on northern England during the morning and early afternoon. At the time, the Luftwaffe considered that there would be few RAF fighters left to defend the north due to combat in the south. However, their intelligence was wrong as the RAF were rotating fighter squadrons between the north and south. Losses for the Luftwaffe were high due to the lack of single-engine fighter protection that could not cross the North Sea because the range was too great.

During the day, attacks were also made on Croydon (mistaken for Kenley), Eastchurch, Hawkinge, Lympne, Martlesham Heath, Portland, Manston, West Malling and the Short Brothers factory at Rochester.

As the Luftwaffe operations in the north declined during the afternoon, at 17.00hrs, Sussex and Hampshire's coastal radars plotted the track of two raids headed towards Southern England. These consisted of a number of Junkers Ju 88A-1s of I/LG1 and II/LG1 escorted by Messerschmitt Bf 110s of II/ZG76. The formations were set upon by Nos. 43, 249, 601 and 609 Squadrons, but despite determined attack by the defenders, the bombers got through. On the receiving end were the airfields at Middle Wallop, Worthy Down and Odiham.

It was a case of mistaken identity for Odiham as the Luftwaffe crews reported they had bombed RAF Andover. Luckily for the airfield, the bombing was ineffectual, most landing around the perimeter with no damage to the runways or buildings. Nevertheless, the day for the Luftwaffe was to become known as Black Thursday and was one of heavy loss with 75 aircraft failing to return to the RAF's 34. A lesson not learnt on this day by Goring was that vast effort was being expended on airfields of little value to weakening the RAF's fighter force, a clear sign of inferior intelligence.

The battle raged over the coming months, with both sides continuing a war of attrition. Tactical errors by Hitler and Goring ensured that the RAF was able to rebuild its strength, as, at one point, there was a distinct chance Britain would not prevail. Thankfully, the Germans could not gain air superiority over Southern England, and Operation Sea Lion was postponed. With the coming of 1941, Hitler decided to attack Russia, which was a big mistake as by his own words he stated, "a war should not be fought on two fronts". However, the mass of men and equipment that went to the Eastern Front took the pressure off the British and slowly, thoughts of taking to the offensive began to gather pace.

On 15 August 1940, large scale attacks were made by Luftflotte 5 based in Norway and Denmark on northern England during the morning and early afternoon. At the time, the Luftwaffe considered that there would be few RAF fighters left to defend the north due to combat in the south. However, their intelligence was wrong as the RAF were rotating fighter squadrons between the north and south. Losses for the Luftwaffe were high due to the lack of single-engine fighter protection that could not cross the North Sea because the range was too great.

During the day, attacks were also made on Croydon (mistaken for Kenley), Eastchurch, Hawkinge, Lympne, Martlesham Heath, Portland, Manston, West Malling and the Short Brothers factory at Rochester.

As the Luftwaffe operations in the north declined during the afternoon, at 17.00hrs, Sussex and Hampshire's coastal radars plotted the track of two raids headed towards Southern England. These consisted of a number of Junkers Ju 88A-1s of I/LG1 and II/LG1 escorted by Messerschmitt Bf 110s of II/ZG76. The formations were set upon by Nos. 43, 249, 601 and 609 Squadrons, but despite determined attack by the defenders, the bombers got through. On the receiving end were the airfields at Middle Wallop, Worthy Down and Odiham.

It was a case of mistaken identity for Odiham as the Luftwaffe crews reported they had bombed RAF Andover. Luckily for the airfield, the bombing was ineffectual, most landing around the perimeter with no damage to the runways or buildings. Nevertheless, the day for the Luftwaffe was to become known as Black Thursday and was one of heavy loss with 75 aircraft failing to return to the RAF's 34. A lesson not learnt on this day by Goring was that vast effort was being expended on airfields of little value to weakening the RAF's fighter force, a clear sign of inferior intelligence.

The battle raged over the coming months, with both sides continuing a war of attrition. Tactical errors by Hitler and Goring ensured that the RAF was able to rebuild its strength, as, at one point, there was a distinct chance Britain would not prevail. Thankfully, the Germans could not gain air superiority over Southern England, and Operation Sea Lion was postponed. With the coming of 1941, Hitler decided to attack Russia, which was a big mistake as by his own words he stated, "a war should not be fought on two fronts". However, the mass of men and equipment that went to the Eastern Front took the pressure off the British and slowly, thoughts of taking to the offensive began to gather pace.

|

After the Battle

At the tail end of 1940, the RAF reviewed its Army Co-operation role, and in December, the new Army Co-operation Command was formed with its headquarters based at Bracknell. There was a need to upgrade the Command's Lysanders to an aircraft of a more modern nature, which could at least have a chance of competing with modern Luftwaffe fighters. |

It was decided that Curtis P-40 Tomahawks would fit the role with the type also capable of photo-reconnaissance duties. In line with the Army Co-operation role changes, Odiham was upgraded with new runways, and a tarmac perimeter track was laid to connect hard-standings. On 1 March 1941, No. 400 (City Of Toronto) RCAF Squadron was renumbered from No. 110 Squadron, initially with Lysanders and then with conversion onto the Tomahawk. The aircraft did not excel as a fighter in the European theatre, but it was far superior to the Lysander and was a good platform for low-level reconnaissance, which was put to very good use by 400 Squadron.

Odiham had been lucky during the Battle of Britain in sustaining no damage from the attention of the Luftwaffe, however in a twist of fate, on 23 March 1941, a lone Ju 88 appeared over the airfield pursued by a Hurricane. To try and hasten his escape, the Ju 88 pilot decided to jettison the aircraft's bomb load just as it happened to be over Odiham. This was not a deliberate attack, but 12 bombs fell within the vicinity of the accommodation blocks with little damage being sustained. Odiham's charmed existence continued when again, on 26 March, another Ju 88 flew low over the airfield, this time without releasing any bombs. However, it did receive attention from the airfield's defences.

Further work began in May 1941 with the lengthening of runways and a transfer to No. 71 Group. Once completed by the Airfield Construction Unit, Odiham's runways were the main running east to west at 5,100ft, the south-west to northeast strip at 4,200ft and the south-east to north-west, which had been abandoned and was in use as an access track.

A former resident returned in the form of No. 13 Squadron from RAF Hooton Park, equipped with Lysanders with conversion to Blenheim IVs following shortly after. Their role was still of cooperation but with additional tasks of low-level bombing, gas spraying and the laying of smoke screens.

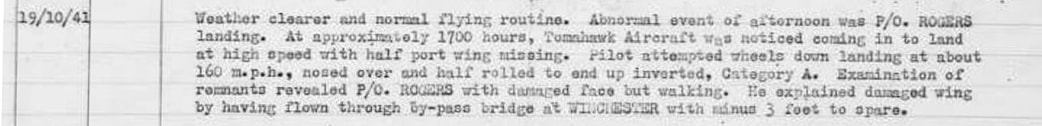

On 19 October 1941, an interesting event was witnessed at the airfield when a No. 400 Squadron Tomahawk flown by Plt Off. Rogers was seen attempting to land with part of its wing missing. The landing was unsuccessful and resulted in Category A damage to the aircraft and some injuries to the pilot. It transpired Rogers had attempted to fly through the bridge located on the Winchester bypass road but had left 3ft of his wing behind when he struck it. From then on, the structure was known as Spitfire Bridge, as it was felt that only the iconic fighter could have attempted such a feat. Rogers was charged over his exploits, but the squadron ORB shows he continued to fly and remained part of the unit.

Odiham had been lucky during the Battle of Britain in sustaining no damage from the attention of the Luftwaffe, however in a twist of fate, on 23 March 1941, a lone Ju 88 appeared over the airfield pursued by a Hurricane. To try and hasten his escape, the Ju 88 pilot decided to jettison the aircraft's bomb load just as it happened to be over Odiham. This was not a deliberate attack, but 12 bombs fell within the vicinity of the accommodation blocks with little damage being sustained. Odiham's charmed existence continued when again, on 26 March, another Ju 88 flew low over the airfield, this time without releasing any bombs. However, it did receive attention from the airfield's defences.

Further work began in May 1941 with the lengthening of runways and a transfer to No. 71 Group. Once completed by the Airfield Construction Unit, Odiham's runways were the main running east to west at 5,100ft, the south-west to northeast strip at 4,200ft and the south-east to north-west, which had been abandoned and was in use as an access track.

A former resident returned in the form of No. 13 Squadron from RAF Hooton Park, equipped with Lysanders with conversion to Blenheim IVs following shortly after. Their role was still of cooperation but with additional tasks of low-level bombing, gas spraying and the laying of smoke screens.

On 19 October 1941, an interesting event was witnessed at the airfield when a No. 400 Squadron Tomahawk flown by Plt Off. Rogers was seen attempting to land with part of its wing missing. The landing was unsuccessful and resulted in Category A damage to the aircraft and some injuries to the pilot. It transpired Rogers had attempted to fly through the bridge located on the Winchester bypass road but had left 3ft of his wing behind when he struck it. From then on, the structure was known as Spitfire Bridge, as it was felt that only the iconic fighter could have attempted such a feat. Rogers was charged over his exploits, but the squadron ORB shows he continued to fly and remained part of the unit.

On 6 November 1941, No. 400 Squadron began operations over France with two Tomahawks carrying out a reconnaissance mission which was hampered by the lack of cloud cover. The squadron continued to hone its skills into 1942, ready for taking the offensive back to the Germans in the coming months and years.

Taking the Offensive

During 1942 the only way the British could take the fight back to Germany was by using the aircraft of Bomber Command. In the early years of the war, Britain's bombing campaign against the Axis forces was somewhat haphazard with no clear plan and inaccurate bombing. The Bomber Command crews were not short of courage or determination, but their equipment was lacking. Something had to be done to make operations more effective for the expended effort and the losses suffered. In February 1942, Arthur T. Harris was appointed to Commander In Chief Bomber Command and was tasked with undertaking the strategic bombing of German industries and cities.

In the early months of Harris's command, bombing accuracy, navigation, and the limited numbers of aircraft continued to hamper his efforts. However, slowly improved navigation aids (GEE) and target marking came into operation along with larger, more capable aircraft, such as the Short Stirling, Handley Page Halifax and Avro Lancaster, that were capable of more extended range and increased bomb-carrying capacity.

During 1942 the only way the British could take the fight back to Germany was by using the aircraft of Bomber Command. In the early years of the war, Britain's bombing campaign against the Axis forces was somewhat haphazard with no clear plan and inaccurate bombing. The Bomber Command crews were not short of courage or determination, but their equipment was lacking. Something had to be done to make operations more effective for the expended effort and the losses suffered. In February 1942, Arthur T. Harris was appointed to Commander In Chief Bomber Command and was tasked with undertaking the strategic bombing of German industries and cities.

In the early months of Harris's command, bombing accuracy, navigation, and the limited numbers of aircraft continued to hamper his efforts. However, slowly improved navigation aids (GEE) and target marking came into operation along with larger, more capable aircraft, such as the Short Stirling, Handley Page Halifax and Avro Lancaster, that were capable of more extended range and increased bomb-carrying capacity.

|

Harris pressed for ever more extensive raids, and the first of these was Operation Millennium, an attack on Cologne using 1,000 bombers over the night of 30/31 May. To achieve his goal of using 1,000 bombers, Harris had to cast his net far and wide. No. 13 Squadron's Blenheims based at Odiham were tasked to fly to RAF Wattisham to join 2 No. Group to participate in diversionary intruder operations. On this occasion, all the squadron's aircraft returned, and the raid itself was deemed a success, with considerable damage caused to apartment blocks, public utilities, industrial sites and many commercial properties.

|

It is estimated 135,000 to 150,000 of the cities populace packed their bags and left. This was the start of the area bombing of Germany that would continue until the end of the war in Europe and would cost tens of thousands of lives on both sides.

A second raid was planned for the night of 1/2 June, this time to Essen with 13 Squadron again carrying out intruder missions. On this occasion, the unit lost a Blenheim IV Z6186 and all crew, who are buried at Reichsweld Forest War Cemetery.

One further 1,000 raid took place again with the involvement of the squadron's Blenheims. On the night of 25/26 June, Harris directed his bombers against Bremen with 13's, along with other No. 2 Group aircraft tasked with intruder operations to Venlo and St Truiden. On this occasion, the squadron lost two Blenheim IVs, T2254 to flak and Z6084, both with the loss of all crew, who are buried in Schoonselhof and Houwaart Cemeteries, respectively.

A second raid was planned for the night of 1/2 June, this time to Essen with 13 Squadron again carrying out intruder missions. On this occasion, the unit lost a Blenheim IV Z6186 and all crew, who are buried at Reichsweld Forest War Cemetery.

One further 1,000 raid took place again with the involvement of the squadron's Blenheims. On the night of 25/26 June, Harris directed his bombers against Bremen with 13's, along with other No. 2 Group aircraft tasked with intruder operations to Venlo and St Truiden. On this occasion, the squadron lost two Blenheim IVs, T2254 to flak and Z6084, both with the loss of all crew, who are buried in Schoonselhof and Houwaart Cemeteries, respectively.

Operation Jubilee

As the summer of 1942 progressed, more squadrons arrived at Odiham with No. 171 flying in from Gatwick with its Tomahawks on 12 July and No. 614 (County Of Glamorgan) coming soon after with Blenheim IVs. Both Nos. 171 and 400 Squadrons flew 'Rhubarb' low-level strike missions from Odiham to France, where they began softening up German defences before a planned operation code-named Jubilee.

The year of 1942 had been bad for the Allies, with great pressure exerted on the Russians on the Eastern Front. In addition, with the earlier attack on Pearl Harbour, the Americans were reeling from material losses and Japanese advances in the Far East, the effects of which were also being felt by the British. There was also the situation in North Africa where Rommel and the Africa Corps were driving back British and Commonwealth troops, all in all, a pretty bleak picture.

For some time, Churchill and the British Chiefs of Staff had been under pressure from the Russians to open a front in the West to stop the Germans from moving further resources to the East. The Americans, whose resources were somewhat stretched, were also making noises that unless there was a second front in the West, they would concentrate their efforts against the Japanese. There was also agitation in Britain and the United States from the public to open a second front to assist the hard-pressed Russians. Rallies were held in both Trafalgar Square and Madison Square Gardens in support of these demands.

From all this and despite some cancellations due to training and weather, Operation Jubilee was planned and executed on 19 August 1942. It was hoped that the operation would either compel the Germans to move forces west to counter the threat of a renewed Allied offensive; and so relieve pressure on the Russians or to keep troops tied up in France and negate the threat of them moving east.

The plan for the operation was for British and Canadian troops, with a small number of US Rangers, to seize and hold the port of Dieppe for two tides, cause as much damage to enemy facilities and defences before withdrawing. This would be the first time the Allies had had a go at attacking Hitler's Atlantic Wall. It was hoped the raid would give valuable experience before any large scale attempt at liberating Europe was attempted.

Over 230 ships and craft made up the assault force, but due to a number of factors, not least running into a German convoy, the defenders were fully aware and prepared for the attack. As a result, the Allied troops went ashore in the face of withering machine gun and artillery fire and were cut down without reaching their pre-planned objectives. Nevertheless, there was success in some quarters with 4 Commando executing a flawless neutralisation of a gun battery on the western flank. A Victoria Cross was awarded to Captain Pat Porteous.

The year of 1942 had been bad for the Allies, with great pressure exerted on the Russians on the Eastern Front. In addition, with the earlier attack on Pearl Harbour, the Americans were reeling from material losses and Japanese advances in the Far East, the effects of which were also being felt by the British. There was also the situation in North Africa where Rommel and the Africa Corps were driving back British and Commonwealth troops, all in all, a pretty bleak picture.

For some time, Churchill and the British Chiefs of Staff had been under pressure from the Russians to open a front in the West to stop the Germans from moving further resources to the East. The Americans, whose resources were somewhat stretched, were also making noises that unless there was a second front in the West, they would concentrate their efforts against the Japanese. There was also agitation in Britain and the United States from the public to open a second front to assist the hard-pressed Russians. Rallies were held in both Trafalgar Square and Madison Square Gardens in support of these demands.

From all this and despite some cancellations due to training and weather, Operation Jubilee was planned and executed on 19 August 1942. It was hoped that the operation would either compel the Germans to move forces west to counter the threat of a renewed Allied offensive; and so relieve pressure on the Russians or to keep troops tied up in France and negate the threat of them moving east.

The plan for the operation was for British and Canadian troops, with a small number of US Rangers, to seize and hold the port of Dieppe for two tides, cause as much damage to enemy facilities and defences before withdrawing. This would be the first time the Allies had had a go at attacking Hitler's Atlantic Wall. It was hoped the raid would give valuable experience before any large scale attempt at liberating Europe was attempted.

Over 230 ships and craft made up the assault force, but due to a number of factors, not least running into a German convoy, the defenders were fully aware and prepared for the attack. As a result, the Allied troops went ashore in the face of withering machine gun and artillery fire and were cut down without reaching their pre-planned objectives. Nevertheless, there was success in some quarters with 4 Commando executing a flawless neutralisation of a gun battery on the western flank. A Victoria Cross was awarded to Captain Pat Porteous.

|

With the first assault wave effectively defeated, the next waves were dealt with in a similar manner by the Germans, and the invaders made little in the way of gain. It took a while for commanders to realise the situation was so dire, and further forces were sent into the ensuing carnage. Finally, at 9.40 am, the signal was given to withdraw, with further losses incurred to naval personnel and the surviving assault troops as they retreated to their landing craft.

|

The raid was, in all essence, a failure that resulted in 4,000 Canadian and British forces being either killed, wounded or taken prisoner. However, the operation gave a valuable insight into what was to be expected in a full assault on occupied Europe. How many Allied military personnel were saved through the sacrifices of those at Dieppe?

|

In July 1942, Odiham's No. 400 Squadron had converted to the North American Mustang Is and, along with No. 13 Squadron's Blenheims, had taken part in the air battle above Dieppe.

Flying on detachment from Gatwick, the Mustangs flew 20 reconnaissance missions monitoring German troop movements in the rear of the battle area, losing one of their number in the process. No. 13 Squadron's Blenheims detached to Thruxton, where they flew to Dieppe to carry out smoke laying duties. |

After Dieppe

After the Squadrons returned from Dieppe, No. 171 moved back to Gatwick and No. 13 converted to Blenheim Vs in preparation to leave with 614 Squadron in November 1942 for the planned Operation Torch, the invasion of North Africa.

After the Squadrons returned from Dieppe, No. 171 moved back to Gatwick and No. 13 converted to Blenheim Vs in preparation to leave with 614 Squadron in November 1942 for the planned Operation Torch, the invasion of North Africa.

|

Joining No. 400 Squadron in the Army Co-operation role at Odiham were Nos. 168 and 239 Squadrons, both flying Mustangs. In early December, No. 400 Squadron moved to Dunsfold, with No. 239 going to Hurn.

The Mustangs of No. 168 Squadron busied themselves on attacking Channel shipping and coastal targets and were soon joined by Nos. 174 and 175 Squadrons flying Hawker Hurricane IIBs in December and January 1943, respectively. |

The opening of 1943 saw the Allies in conference at Casablanca with Churchill, Roosevelt and their advisers discussing the way forwards regarding the War's course. At the meeting, it was decided that 'unconditional surrender' was the Allies stated aim for the conflict's conclusion against the Axis powers, and nothing less would suffice. On the Eastern Front, the German 6th Army surrendered at Stalingrad, and Montgomery was taking on Rommel in Libya and was winning. Things were looking up for the Allies.

In Lincolnshire, one of the War's most outstanding feats was launched from RAF Scampton. On the night of 16/17 May, No. 617 Squadron led by Guy Gibson attacked German Dams, breaching two of them, the Mohne and the Eder. Once again, Bomber Command was taking the war to the enemies heartland, a trend that continued until the conflict's end.

The two Hurricane squadrons recently arrived at Odiham stayed but for a brief time, and more Mustangs came, with those of Nos. 170, 268 and elements of No. 2 Squadron arriving during May/June 1943. Odiham became an all Mustang airfield and transferred to Fighter Command with 123 Airfield Headquarters established in tented accommodation within the old bomb dump. The Mustangs ranged far and wide over Northern France, carrying out the task of tactical reconnaissance, seeking out radar stations, enemy HQs and supply bases.

The Allies military planners were now considering their options for an invasion of Europe, which was expected to take place sometime in 1944. As part of the plans, Allied air power was reorganised, with the Army Co-operation Command being disbanded and the formation of the Second Tactical Air Force (2nd TAF). The TAF also took units from Fighter and Bomber Command and began training to support the Allied Armies in the field. Fighter Command itself was renamed the Air Defence of Great Britain, a title it kept until reverting back later in 1943.

In Lincolnshire, one of the War's most outstanding feats was launched from RAF Scampton. On the night of 16/17 May, No. 617 Squadron led by Guy Gibson attacked German Dams, breaching two of them, the Mohne and the Eder. Once again, Bomber Command was taking the war to the enemies heartland, a trend that continued until the conflict's end.

The two Hurricane squadrons recently arrived at Odiham stayed but for a brief time, and more Mustangs came, with those of Nos. 170, 268 and elements of No. 2 Squadron arriving during May/June 1943. Odiham became an all Mustang airfield and transferred to Fighter Command with 123 Airfield Headquarters established in tented accommodation within the old bomb dump. The Mustangs ranged far and wide over Northern France, carrying out the task of tactical reconnaissance, seeking out radar stations, enemy HQs and supply bases.

The Allies military planners were now considering their options for an invasion of Europe, which was expected to take place sometime in 1944. As part of the plans, Allied air power was reorganised, with the Army Co-operation Command being disbanded and the formation of the Second Tactical Air Force (2nd TAF). The TAF also took units from Fighter and Bomber Command and began training to support the Allied Armies in the field. Fighter Command itself was renamed the Air Defence of Great Britain, a title it kept until reverting back later in 1943.

|

Changes continued at Odiham with the arrival of No. 4 Squadron in August and No. 268 Squadron leaving for Funtington in Sussex on 15 September. Also departing the same month were Nos. 168 and 170 Squadrons, with Nos. 2 and 4 Squadrons on 15 November.

The departure of Odiham's Squadrons left the airfield deserted until the arrival of No. 511 Forward Repair Unit (FRU) in December, which brought a number of aircraft that required maintenance and repair. |

Vengeance Weapons

|

The end of 1943 saw Italy declaring War on Germany, the Anzio landings and the arrival at Odiham of two Hawker Typhoon squadrons. In early 1944, Nos. 181 and 274 carried out attacks on 'Noball' sites, which was the name given to Hitler's V weapon launch locations in France. As early as May 1943, the Allies had become aware of the existence of construction sites in Northern France to launch V1 flying bombs and V2 rockets. The plans Hitler had to use these weapons became a priority for the Allies to defeat, and a number of operations were put in place.

|

Operation Hydra took place over the night of 17/18 August 1943 with Bomber Command attacking the Peenemunde Army Research Centre, with the aim of destroying the research facilities and killing the scientists. This was the opening of Crossbow, the Allies strategic bombing campaign against the Nazi V weapon programme. The raid on Peenemunde resulted in a seven-week delay in V weapon production but came at a loss of 40 Bomber Command aircraft, 215 crew and many foreign workers in a nearby concentration camp.

The Noball attacks by Odiham's Typhoons, who had flown in from Merston in Sussex, were part of an intensive assault on the V1 launch sites, and their contribution lasted for two weeks before they departed back to their home airfield. The Typhoon was intended to be a high altitude interceptor and successor to the Hurricane. However, the aircraft never excelled in its intended role but became a formidable low-level fighter bomber; its strengths exploited to the full in the invasion of Europe.

The Noball attacks by Odiham's Typhoons, who had flown in from Merston in Sussex, were part of an intensive assault on the V1 launch sites, and their contribution lasted for two weeks before they departed back to their home airfield. The Typhoon was intended to be a high altitude interceptor and successor to the Hurricane. However, the aircraft never excelled in its intended role but became a formidable low-level fighter bomber; its strengths exploited to the full in the invasion of Europe.

The Build-Up to D-Day

|

With their sights firmly set on liberating Europe, the Allies stepped up their aerial campaign. The south of England became a land-based aircraft carrier to launch operations, designed to soften up the Nazi Occupiers, especially for fighters, tactical support and transport. As a result, airfields sprung up all over the south, many of a very temporary nature.

On 18 February 1944, No. 400 Squadron returned to Odiham with their Spitfire PR MK.IXs and Mosquito PR XVIs, they were then joined briefly by No. 184 Squadron, flying Typhoons. |

The build-up continued at Odiham with the arrival of Nos. 168, 414 (Swordfish) and 430 (City Of Sudbury) Squadrons, flying a mix of Spitfires, Typhoons and Mustangs, the two Canadian squadrons forming 128 Airfield, of 128 (Fighter) RCAF Wing, No. 83 Group, 2nd TAF. Operations were undertaken both day and night with Odiham and the surrounding area, resounding to the sound of Rolls Royce Merlin, Napier Sabre and Allison V-1710 aero engines.

D-Day

The role of No. 511 FRU increased during 1944 with detachments of personnel working off-site in readiness for D-Day. The airfield was filled with aircraft, and two additional T.2 hangars were built to give a measure of protection to the maintenance crews. Odiham's location was high on a plateau, even in summer the weather could be inclement, which did not afford the best working conditions for those tasked with aircraft repairs. As D-Day approached, the airfield was sealed off from outside contact, and all guessed that the invasion was imminent.

The role of No. 511 FRU increased during 1944 with detachments of personnel working off-site in readiness for D-Day. The airfield was filled with aircraft, and two additional T.2 hangars were built to give a measure of protection to the maintenance crews. Odiham's location was high on a plateau, even in summer the weather could be inclement, which did not afford the best working conditions for those tasked with aircraft repairs. As D-Day approached, the airfield was sealed off from outside contact, and all guessed that the invasion was imminent.

|

The date originally set for D-Day (Operation Overlord) was 4 June 1944, but as ever, bad weather in the Channel brought a 24-hour postponement.

A series of deceptions had fooled the Germans into thinking that the assault would occur in the Pas-de-Calais area, so when the invasion came on the 6th June in Normandy, the enemy was unprepared and caught off guard. |

|

A period of being brought to readiness only to be stood down was causing frustration at Odiham. Finally, however, the signal was given that the invasion was on and 128 Wing was ready and waiting to fly in support of those on the ground. No. 168 Squadron flew 36 tactical reconnaissance missions on the day, with the loss of one Mustang I, AM225 flown by Fg Off. S H Barnard, hit by gunfire from Allied shipping with the pilot's loss. No. 430 Squadron lost a Mustang I AG465 flown by Fg Off. L R Allman when it was shot down by an FW190 near Evreux, again with the loss of the pilot who is buried in Bretteville-sur-Laize Canadian War Cemetery.

|

A further No. 168 Squadron Mustang was lost on 7 June when AM128 flown by Fg Off. J C Low was shot down by JG26 east of Argentan with the loss of the pilot, who is buried in Evreux Cemetery. However, No. 414 Squadron appeared to have been very lucky during the invasion air war and did not lose an aircraft until 14 June, when Mustang I AP205 flown by Fg Off. R C Brown was hit by flak near Le Beny-Bocage, with the pilot bailing out and becoming a POW.

With progress being made in Normandy, airstrips were built to allow squadrons to operate closer to their support area. On 28 June, No. 430 Squadron left Odiham for B-8, a dusty strip near Sommervieu, Bayeaux, followed by Nos. 168 and 400 Squadron's Spitfire PR IXs. The Mosquitos of No. 400 Squadron stayed until 14 August before leaving with No. 414 Squadron to catch up with No. 39 (Reconnaissance) Wing as it was now known.

With progress being made in Normandy, airstrips were built to allow squadrons to operate closer to their support area. On 28 June, No. 430 Squadron left Odiham for B-8, a dusty strip near Sommervieu, Bayeaux, followed by Nos. 168 and 400 Squadron's Spitfire PR IXs. The Mosquitos of No. 400 Squadron stayed until 14 August before leaving with No. 414 Squadron to catch up with No. 39 (Reconnaissance) Wing as it was now known.

Activity at Odiham did not diminish with No. 511 FRU continuing to carry out works on an ever-increasing number of aircraft and with the arrival of No. 130 Wing from Gatwick on 27 June. Nos. 2 and 268 Squadrons operated their Mustang Ia aircraft in the tactical reconnaissance role, while No. 4 Squadron flew Spitfire PR IXs. The HQ unit was renamed No. 35 (Reconnaissance) Wing and was flying 50 to 60 sorties a day, searching for signs of enemy troop movements, bunkers and transport hubs.

|

At the end of July, No. 2 Squadron departed to B-10 Plumetot, with No. 268 Squadron following in August. Hot on their heels, No. 4 Squadron moved its Spitfires to the Continent along with part of No. 511 FRU.

Odiham was now somewhat deserted following the move of the squadrons to Europe, with No. 1516 Blind/Beam Approach/Radio Aids Training Flight (BAT) arriving on 17 September 1944, flying Airspeed Oxford aircraft. |

|

As the European bombing campaign was stepped up by Bomber Command and the US 8th Air Force, increasing numbers of aircraft were damaged by fighters, flak and maybe with wounded aboard, would be looking for a safe haven to land.

Many airfields in the south of England would have had unexpected visitors, not least Odiham. How many stood on the ground willing the pilots to get the aircraft down in one piece, we can only imagine. The relief of the crews to be back on terra firma, well only they can tell that story. |

A New Menace

|

In response to the invasion of Europe, Hitler retaliated by sending over scores of V1 flying bombs, with the first falling on London on 13 June 1944, one week after the start of Overlord. Hundreds were targeted at south-east England, with most crossing over Sussex and Kent, but with some entering Hampshire's airspace.

The weapon was a very unnerving as it had a unique sound created by its Argus pulse jet engine. Furthermore, it was highly inaccurate, indiscriminate and could do a lot of damage when it came to earth. |

The V1 would be launched from its sites in Northern France and fly on a predetermined course controlled by onboard gyros. The craft's sound gave it nicknames such as Doodlebug and Buzz Bomb and became feared by the populace of Southern England for its erratic and unpredictable nature. When the engine stopped, it would go into a terminal dive, after which the warhead would detonate upon impact.

|

To counter the threat, scores of anti-aircraft guns were used to shoot down the V1s as flying in a straight, predictable line, they could easily be tracked but were a very small target. Many were brought down, but some still got through.

Air interception was also implemented, and the day's fastest aircraft were sent up to bring the V-1s down. Tempests, Spitfires, Mosquitos and even Meteors all had a go at anti Diver operations, the name given to the air interception of V1s. Odiham participated in the operations with No. 96 Squadron equipped with Mosquito NF VIII aircraft moving to the airfield from Ford in mid-September 1944. |

Interception of the V1s was a hazardous occupation as attacking from the rear often resulted in the warhead detonating in the face of the attacking fighter. Another way to counter the bomb was to if you could catch it, fly alongside, slide your wing under the bomb's wing and tip it over where it would plummet to the ground. Unfortunately, trade was sparse for No. 96 Squadron, and they disbanded on 12 December 1944.

Another more sinister threat came to earth in Chiswick on 8 September 1944 with no warning or sound. The V2 rocket, the second of Hitler's Vengeance weapons, was the World's first intercontinental ballistic missile and would continue to fall on the UK until the end of March 1945.

Towards Wars End

The war was drawing near to ending, but Hitler still had some surprises up his sleeve. In December 1944, the Germans launched their last offensive in the west with an attack through the Ardennes, which caught the Allies completely off guard. The plan was to drive an attack through to the port of Antwerp, thus cutting off the Allied supply route. Bad weather hampered Allied air operations, and in what was to become known as the Battle of the Bulge, initial advances were made, but the Allies prevailed and pushed the offensive back. The Germans capacity to fight was now severely depleted, and they were unable to replace their losses.

The last major attack by the Luftwaffe took place on 1 January 1945 and was in support of the Battle of the Bulge. Operation Bodenplatt was planned to catch the Allies aircraft off guard and gain air superiority to allow the stalled advance of the German Army and Waffen SS on the battlefield. The attack was a surprise, and many Allied aircraft were lost on the ground. However, the operation was ultimately a failure, with the Luftwaffe losing many machines and, more crucially, pilots, which could not be replaced at this stage of the war.

Back at Odiham, No. 511 FRU had disbanded, and No. 604 Squadron, flying Mosquito NF XIIIs, arrived in December 1944 from Predannack in Cornwall. By mid-December, No. 147 Wing unit, No. 264 Squadron, flew in with their Mosquito NF VIIIs. Both Nos. 604 and 264 Squadrons had left by the year's end, leaving Odiham with only the Oxfords of No. 1516 BAT flight in residence.

|

In January 1945, Dunsfold was taken over as satellite to Odiham, with activity at the latter being very sparse.

This changed in April when scores of Douglas C-47 Dakotas started repatriating POWs from the Continent to the airfield for medical checkups, re-kitting and documentation before being sent on leave. The sight of a C-47 to many POWs would have been one of the most welcome. Some would have been in captivity since Dunkirk in May 1940, with others longer than that. |

On 7 June 1945, Odiham transferred from Fighter (No. 11 Group) to Transport Command (No. 46 Group) with station HQ staff arriving from RAF Blakehill Farm. Soon after, Dakotas of No. 233 Squadron arrived and began scheduled flights to the continent, joined in August by a detachment of C-47s from No. 437 Squadron RCAF. The Dakotas ferried fuel, medical supplies and food to the Continent, bringing back troops and rumour has it, William Joyce, the infamous Lord Haw-Haw, who kept the Allies entertained with his propaganda broadcasts from Germany throughout the war.

Wars End

The war in Europe ended on 8 May 1945 with Churchill broadcasting from the Cabinet Room that a ceasefire had been signed at the American Headquarters Rheims at 02.41 hrs. Huge celebrations took place to mark VE day as those of all nations danced, sang and drank to the end of the European War, a conflict that had cost the lives of millions, both military and civilian.

With the war in Europe won, there was still the question of Japan to settle. Tiger Force (Very Long Range Bomber Force) was planned as the Commonwealth air contribution to the invasion of mainland Japan. Tiger Force was proposed to be composed of Avro Lancasters, Lincolns, and Consolidated Liberators with escorts provided by Hawker Tempest IIs of Nos. 183 and 247 Squadrons who were at the time working up at RAF Chilbolton. However, the dropping of the two atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki brought the war in the East to an end, and the need for Tiger Force was negated.

Japan surrendered to the Allies on 15th August 1945 with an official signing of the documents on 2 September aboard the American battleship, USS Missouri bringing World War Two to its conclusion after six years of bitter fighting.

On 23 August, No. 233 Squadron left Odiham for the Far East, with No. 271 Squadron taking their place at the end of the month, with the scheduled flights continuing.

With the war in Europe won, there was still the question of Japan to settle. Tiger Force (Very Long Range Bomber Force) was planned as the Commonwealth air contribution to the invasion of mainland Japan. Tiger Force was proposed to be composed of Avro Lancasters, Lincolns, and Consolidated Liberators with escorts provided by Hawker Tempest IIs of Nos. 183 and 247 Squadrons who were at the time working up at RAF Chilbolton. However, the dropping of the two atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki brought the war in the East to an end, and the need for Tiger Force was negated.

Japan surrendered to the Allies on 15th August 1945 with an official signing of the documents on 2 September aboard the American battleship, USS Missouri bringing World War Two to its conclusion after six years of bitter fighting.

On 23 August, No. 233 Squadron left Odiham for the Far East, with No. 271 Squadron taking their place at the end of the month, with the scheduled flights continuing.

Post War

In October 1945, No. 271 Squadron left Odiham, which allowed the airfield to be transferred to the RCAF. Early November saw the arrival of 120 (RCAF) Wing, who took control of the site and also RAF Down Ampney. No. 437 Squadron RCAF arrived with their Dakotas on the 15 November, leaving a detachment at B56 Evere, with No. 436 Squadron RCAF, also with Dakotas, arriving on 4 April 1946. The scheduled flights continued until the two squadrons were, without much notice, disbanded on 28 June. The airfield was then handed back to the RAF, becoming part of No. 11 Group Southern Sector.

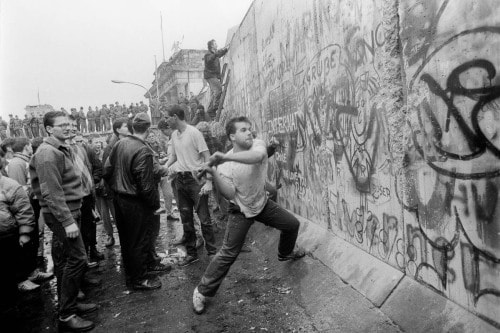

The war may be over, but a new type of hostility became apparent, the stand-off between East and West. This became known as the Cold War and continued well into the 1980s. Odiham was to play its part and also in other future conflicts. The two sides never came to blows militarily, but they did fight proxy wars, such as in Vietnam and Afghanistan, which again cost many lives, both military and civilian. The power of the atom bomb kept the two sides from attacking each other, as a nuclear war would have resulted in the destruction of both sides, something known as Mutually Assured Destruction, the acronym MAD being very apt.

In October 1945, No. 271 Squadron left Odiham, which allowed the airfield to be transferred to the RCAF. Early November saw the arrival of 120 (RCAF) Wing, who took control of the site and also RAF Down Ampney. No. 437 Squadron RCAF arrived with their Dakotas on the 15 November, leaving a detachment at B56 Evere, with No. 436 Squadron RCAF, also with Dakotas, arriving on 4 April 1946. The scheduled flights continued until the two squadrons were, without much notice, disbanded on 28 June. The airfield was then handed back to the RAF, becoming part of No. 11 Group Southern Sector.

The war may be over, but a new type of hostility became apparent, the stand-off between East and West. This became known as the Cold War and continued well into the 1980s. Odiham was to play its part and also in other future conflicts. The two sides never came to blows militarily, but they did fight proxy wars, such as in Vietnam and Afghanistan, which again cost many lives, both military and civilian. The power of the atom bomb kept the two sides from attacking each other, as a nuclear war would have resulted in the destruction of both sides, something known as Mutually Assured Destruction, the acronym MAD being very apt.

Into the Jet Age

As the war came to a close, jet aircraft began to be seen in the skies, the most successful of which was the Luftwaffe's Messerschmitt Me 262 in its combat record. The British had developed the Gloster Meteor, and although it had never met the 262 in combat, it is difficult to conclude which aircraft would have prevailed in a dogfight. The 262 was more advanced and faster than the Meteor, but its Junkers Jumo 004 B-1s turbojets were notoriously unreliable.