RAF Ludford Magna

Airfield Code Letters - LM

Those driving south-east down the B1225 road soon after leaving Ludford in all likelihood will give no real thought to the patch of open farmland on their left. Why should they, as there is no particular evidence now to suggest that this land once housed some of the RAF's most important and secretive Lancasters. All is calm now at former RAF Ludford Magna, but at the height of Bomber Command's offensive against occupied Europe, the airfield would have been a hive of activity.

Many Lancasters and crew left Ludford Magna never to return, a higher proportion than was typical for a Bomber Command station. Their mission was not only to carry bombs but also to confound the Luftwaffe night fighters and German ground defences as the world of electronic warfare evolved.

Those driving south-east down the B1225 road soon after leaving Ludford in all likelihood will give no real thought to the patch of open farmland on their left. Why should they, as there is no particular evidence now to suggest that this land once housed some of the RAF's most important and secretive Lancasters. All is calm now at former RAF Ludford Magna, but at the height of Bomber Command's offensive against occupied Europe, the airfield would have been a hive of activity.

Many Lancasters and crew left Ludford Magna never to return, a higher proportion than was typical for a Bomber Command station. Their mission was not only to carry bombs but also to confound the Luftwaffe night fighters and German ground defences as the world of electronic warfare evolved.

The Airfield and the Squadrons

|

In June 1942, the contractor George Wimpey commenced construction of a Class A airfield at Ludford Magna. Three runways were laid 02-20 at 1,950 yards, 11-29 at 1,430 yards and 15-33 at 1,400 yards. Thirty-six hardstandings were connected to the perimeter track. Hangars were provided in the form of four T2s off the southern perimeter, a single T2 to the east and a T2 and B1 on the station technical site near the village. Domestic, communal, mess and sick quarter sites were dispersed in farmland to the north of the airfield, with accommodation provided for 1,953 males and 305 females. Ludford Magna was an airfield built on a very temporary basis, as were many Bomber Command fields of the day. Being farmland in a previous life, the site soon became known as Mudford Magna.

|

At 430ft above sea level, Ludford Magna was the highest airfield in Lincolnshire, giving it a very exposed position in the Wolds. The main runway was aligned north to south which caused problems for aircraft of the day, especially Lancasters which could be a handful on take-off and landing in a crosswind.

The airfield was opened under the command of 1 Group on 15 June 1943, with Lancasters of 101 Squadron arriving from their former Yorkshire base of Holme-on-Spalding Moor.

In October 1943, changes took place at the station when it took over RAF Wickenby as a satellite. December of the same year saw Ludford Magna become headquarters of 14 Base, adding RAF Faldingworth to its control. Later in the year, in November, it was proposed a second flying unit be created at the airfield. 576 Squadron was to be formed using a nucleus of four crews from 101 and others from 103 Squadron, at the time based at RAF Elsham Wolds. However, the conditions at Ludford Magna were so atrocious and the facilities limited, 576 Squadron went on to be formed at 103 Squadron's home base.

Between April and July 1944, 1682 Bomber Defence Training Flight were stationed at the airfield. The Flight used its Hurricanes to carry out simulated attacks on Bomber Command aircraft to give gunners and crew training to tackle live fighter aircraft.

The airfield was opened under the command of 1 Group on 15 June 1943, with Lancasters of 101 Squadron arriving from their former Yorkshire base of Holme-on-Spalding Moor.

In October 1943, changes took place at the station when it took over RAF Wickenby as a satellite. December of the same year saw Ludford Magna become headquarters of 14 Base, adding RAF Faldingworth to its control. Later in the year, in November, it was proposed a second flying unit be created at the airfield. 576 Squadron was to be formed using a nucleus of four crews from 101 and others from 103 Squadron, at the time based at RAF Elsham Wolds. However, the conditions at Ludford Magna were so atrocious and the facilities limited, 576 Squadron went on to be formed at 103 Squadron's home base.

Between April and July 1944, 1682 Bomber Defence Training Flight were stationed at the airfield. The Flight used its Hurricanes to carry out simulated attacks on Bomber Command aircraft to give gunners and crew training to tackle live fighter aircraft.

|

In connection with Ludford Magna's FIDO installation, an Airspeed Oxford of 1546 Beam Approach Training Flight was detached to the field and used for trials and communications work. A post-war re-organisation of Bomber Command saw 101 Squadron move to nearby RAF Binbrook on 1 October 1945. After this, the airfield was placed on Care and Maintenance, and all flying ceased, although the runways remained intact for emergency use. The site was then handed over to the Ministry of Agriculture, with cultivation taking place between the runways.

|

In 1958 part of the airfield was reactivated for use with Thor ICBM (Inter-Continental Ballistic Missile). 104 Squadron was formed in July 1959 to operate three ICBMs under the RAF Hemswell Missile Wing. Thor facilities stayed at the airfield until May 1963, when the missiles were withdrawn and the squadron disbanded.

In 1965-66 the 780-acre site was sold off with the runways removed, and the airfield returned to agriculture. Some of the hardcore from the runways found its way into the Humber Bridge construction works.

In 1965-66 the 780-acre site was sold off with the runways removed, and the airfield returned to agriculture. Some of the hardcore from the runways found its way into the Humber Bridge construction works.

FIDO

|

Due to its location high in the Lincolnshire Wolds, Ludford Magna made it probably one of the worst airfields that RAF personnel could be posted. As a result, not was only 101 Squadron fighting German night fighters and ground defences, but also the weather.

Given the importance Bomber Command placed on 101 Squadron's operations, Ludford Magna was one of the first of Lincolnshire's airfields to be equipped with FIDO (Fog Investigation and Dispersal Operation). The installation took place in 1944. |

The system consisted of pipelines being installed along the length of the main runway through which fuel was pumped and then ignited at burners. The result was a wall of flame from which the heat would disperse any fog, thus allowing aircraft to locate the airfield and land. One interesting effect from FIDO was the difficulty of landing four-engine bombers when it was lit. The aircraft tended to float on the thermals created by the heat. This necessitated aircraft having to be flown onto the ground rather than using the usual method of flaring. The cost of running FIDO was colossal, but this was offset in the saving of aircrew lives when weather conditions on return to base were challenging to say the least.

101 Squadron and Ludford Magna

To all intents and purposes, 101 Squadron was the only squadron to operate from Ludford Magna during World War Two. The squadron's role was of a specialist nature, and it's only right to explain and expand on their exploits here.

Following their arrival at the airfield from Holme, the squadron was soon in action. On 21/22 June 1943, an operation to Krefeld resulted in 101 Squadron's first loss while flying from their new home base. Lancaster I ED650 SR-L crashed near Monchengladbach with the loss of all crew. This was the first of many losses that the squadron suffered in the coming months and years.

Over the night of 17/18 August 1943, 101 Squadron took part in one of the most important raids of the war. The Allies had become aware that a new form of weapon was being developed by the Nazis. This was the V-1 flying bomb and the V-2 ballistic missile. Bomber Command was tasked to attack the research facility at Peenemunde and destroy the site, or at least delay production.

Forty aircraft were lost on this raid, but on this occasion, all of the squadron's Lancasters returned safely, with 20 taking off from Ludford Magna and 17 reaching the target to bomb. It is estimated that the attack delayed V-2 production by two months.

The Peenemunde raid saw the first use of Schräge Musik armed night-fighters by the Luftwaffe. These aircraft were fitted with upward-firing cannons, allowing the fighters to sneak up under the bombers without being seen by the defending gunners. Once under the bomber, the fighter would open fire with devastating results for the target.

To all intents and purposes, 101 Squadron was the only squadron to operate from Ludford Magna during World War Two. The squadron's role was of a specialist nature, and it's only right to explain and expand on their exploits here.

Following their arrival at the airfield from Holme, the squadron was soon in action. On 21/22 June 1943, an operation to Krefeld resulted in 101 Squadron's first loss while flying from their new home base. Lancaster I ED650 SR-L crashed near Monchengladbach with the loss of all crew. This was the first of many losses that the squadron suffered in the coming months and years.

Over the night of 17/18 August 1943, 101 Squadron took part in one of the most important raids of the war. The Allies had become aware that a new form of weapon was being developed by the Nazis. This was the V-1 flying bomb and the V-2 ballistic missile. Bomber Command was tasked to attack the research facility at Peenemunde and destroy the site, or at least delay production.

Forty aircraft were lost on this raid, but on this occasion, all of the squadron's Lancasters returned safely, with 20 taking off from Ludford Magna and 17 reaching the target to bomb. It is estimated that the attack delayed V-2 production by two months.

The Peenemunde raid saw the first use of Schräge Musik armed night-fighters by the Luftwaffe. These aircraft were fitted with upward-firing cannons, allowing the fighters to sneak up under the bombers without being seen by the defending gunners. Once under the bomber, the fighter would open fire with devastating results for the target.

Ludford's first commander was Group Captain Bobby Blucke, a man well suited to the task of electronic warfare. Blucke as a pilot had previously been involved in the development of radar and, when war broke out, work with Blind Approach Training and Wireless Investigation Development.

As Bomber Command's offensive over occupied Europe increased, the German defences duly responded, and a game of cat and mouse developed between the two sides. Radar guided Luftwaffe night-fighters started to take an increasing toll on the RAF bombers. Consequently, there was a need within Bomber Command for electronic countermeasures to be further implemented to thwart the growing German defences. First came Window, strips of aluminium foil designed to confuse radar, followed by Airborne Cigar (ABC).

As Bomber Command's offensive over occupied Europe increased, the German defences duly responded, and a game of cat and mouse developed between the two sides. Radar guided Luftwaffe night-fighters started to take an increasing toll on the RAF bombers. Consequently, there was a need within Bomber Command for electronic countermeasures to be further implemented to thwart the growing German defences. First came Window, strips of aluminium foil designed to confuse radar, followed by Airborne Cigar (ABC).

|

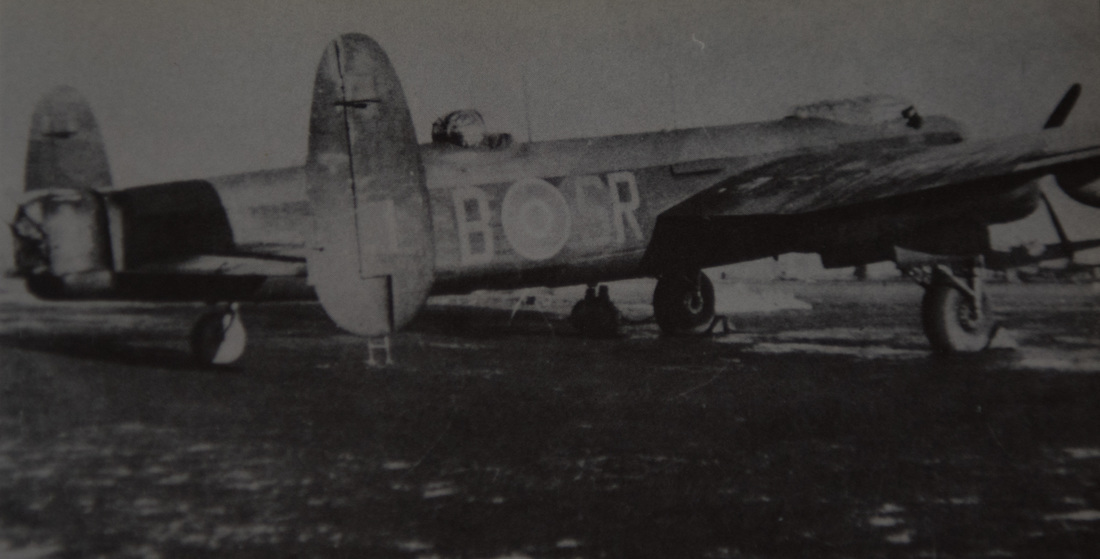

After their arrival at Ludford, 101 Squadron were chosen to be equipped with the RAF's most secretive of Lancasters. In the evolving world of electronic warfare, the squadron's aircraft were fitted with the equipment known as ABC.

The only external difference with these Lancasters was the fitting of two aerials on the top of the aircraft's fuselage and one on the starboard of the bomber's nose. The H2S radar was also omitted. |

The Lancasters of 101 Squadron carried an eighth crew member to operate the special equipment. While on the ground, the aircraft would always be under armed guard, which again shows just how concerned the RAF was in ensuring the aircraft remained secret.

The equipment within the aircraft consisted of a panoramic receiver and three 50-watt transmitters, each capable of sending out frequency-modulated jamming signals. The transmitters were tuned to the wavebands of 30-33 MHz, 38.3-42.5MHz and 48-52 MHz as used by German radios. The black boxes, which weighed in at over 600Ibs, were located in the Lancaster's mid-section. This extra weight would dictate that 101 Squadron's Lancasters carried 1,000Ib less in bomb load. The additional crew member, known as a Special Operator, would locate and lock on to Luftwaffe night-fighter controller transmissions and then use transmitters to jam the signals through the Lancaster's aerials.

The squadron's aircraft operated as part of the main bomber force. The additional crew member often was a fluent German speaker, who was used to intrude on enemy voice transmissions. Many of the Special Operators were those who had fled from Nazi Germany before the war or after their countries had been invaded. Some were Jewish refugees who were given English sounding names to protect them, should they bail out over occupied Europe.

The equipment within the aircraft consisted of a panoramic receiver and three 50-watt transmitters, each capable of sending out frequency-modulated jamming signals. The transmitters were tuned to the wavebands of 30-33 MHz, 38.3-42.5MHz and 48-52 MHz as used by German radios. The black boxes, which weighed in at over 600Ibs, were located in the Lancaster's mid-section. This extra weight would dictate that 101 Squadron's Lancasters carried 1,000Ib less in bomb load. The additional crew member, known as a Special Operator, would locate and lock on to Luftwaffe night-fighter controller transmissions and then use transmitters to jam the signals through the Lancaster's aerials.

The squadron's aircraft operated as part of the main bomber force. The additional crew member often was a fluent German speaker, who was used to intrude on enemy voice transmissions. Many of the Special Operators were those who had fled from Nazi Germany before the war or after their countries had been invaded. Some were Jewish refugees who were given English sounding names to protect them, should they bail out over occupied Europe.

Crewing up of bombers took place at Operational Training Units where, through a strange ritual, individual aircrew mingled and eventually came together as a fully formed crew. This process led to a tightly knit bond between the crew members. It often resulted in the Special Operators, 'specialists' being classed as 'outsiders' as they were not part of the initial crewing up process. The specialists often formed their own group within the squadron and were billeted in their own quarters away from others. It is sometimes stated that the reason for this was should they talk in their sleep, no one else would hear them give away their secrets!

ABC Operations Begin

|

On 22/23 September 1943, the first extended trial using ABC Lancasters took place when two aircraft took part in a raid on Hanover. On this raid, the first German words were heard by an ABC Operator, "Achtung English bastards coming", a phrase which has gone down in 101 Squadron legend.

The following night three ABC Lancasters were sent to Mannheim, where one, JA977 SR-J, flown by Fg Off Don Turner, was damaged by enemy action, which resulted in the Lancaster exploding shortly afterwards. Two crew survived to become prisoners of war. |

By 6 October 1943, half of the squadron's Lancasters then on strength had been converted to carry ABC. The first full-scale operation for the ABC Lancasters took place on 7/8 October, when 343 Lancasters raided Stuttgart with no loss to the squadron.

So began operations for the squadron, which saw them taking part in all Main Force raids. This shows the importance placed upon their capabilities in taking on the Luftwaffe's ground and air defences. At least eight ABC Lancasters were expected to fly spaced at eight-mile intervals in the bomber stream to give maximum jamming coverage. Moreover, even on nights when 1 Group was stood down, 101 Squadron were still expected to contribute their aircraft to support other Groups, making the unit one of the busiest in Bomber Command, with little rest for the crews.

So began operations for the squadron, which saw them taking part in all Main Force raids. This shows the importance placed upon their capabilities in taking on the Luftwaffe's ground and air defences. At least eight ABC Lancasters were expected to fly spaced at eight-mile intervals in the bomber stream to give maximum jamming coverage. Moreover, even on nights when 1 Group was stood down, 101 Squadron were still expected to contribute their aircraft to support other Groups, making the unit one of the busiest in Bomber Command, with little rest for the crews.

|

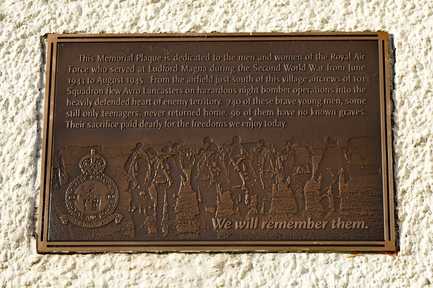

Consequently, with such a high number of operations taking place, 2,477 sorties to be precise, 101 Squadron lost 171 Lancasters while flying from Ludford, resulting in the loss of 740 killed, 96 of them with no known grave. Thus, it can easily be seen why the unit suffered one of the highest loss rates in Bomber Command throughout the war, with 1,040 men killed.

The Squadron took part in many notable operations, including the Battle of Berlin and the disastrous attack on Nuremberg over the night of 30/31 March 1944. |

On this night, Bomber Command lost 94 bombers making this the highest loss on a single raid of the war. Seven 101 Lancasters failed to return from Nuremberg, a considerable loss to the close-knit squadron. Another operation with a significant loss occurred on 3/4 May 1944 to Mailly-le-Camp, 42 bombers failed to return, 4 from 101 Squadron. On the night of 5/6 June 1944, D-Day, 21 of the squadron's Lancasters were over the Channel to stop any Luftwaffe night fighters attacking the troop laden transport aircraft engaged in the operation to liberate Europe.

In the dying days of the Luftwaffe, they were still able to make a nuisance of themselves. On 3 March 1945, an intruder shot up Ludford Magna airfield and village. Luckily very little in the way of damage was caused, and the intruder escaped unscathed. No 101 Squadrons final raid of the war was on 25 April 1945 when Hitler's Berchtesgaden was attacked, with no loss to the unit.

In the dying days of the Luftwaffe, they were still able to make a nuisance of themselves. On 3 March 1945, an intruder shot up Ludford Magna airfield and village. Luckily very little in the way of damage was caused, and the intruder escaped unscathed. No 101 Squadrons final raid of the war was on 25 April 1945 when Hitler's Berchtesgaden was attacked, with no loss to the unit.

The Rose Turret

|

It became apparent in the early days of World War Two that bombers armed with .303" Browning machine guns could not defend themselves against modern cannon-armed fighters. Not only were the bombers' guns out-ranged, but they also lacked the hitting power to cause serious damage to the fighters armour plate, especially night fighters later in the bombing campaign. One person who knew this was Sir Arthur Harris. When he was appointed Commander In Chief of Bomber Command in February 1942, he set about trying to improve his bombers defensive armament.

|

Frustrated by the slowness of the usual design and procurement processes for equipment, he approached the Gainsborough engineering company, Rose Brothers, to develop a turret design that would house more powerful guns. The Rose Turret, as it was christened, was duly designed and delivered by the company ready for installation into Bomber Command Lancasters.

The design consisted of two 0.5" Browning machine guns that offered a greater range and, with a bigger bullet, more destructive power and penetration. It also allowed the gunner to sit on his parachute and escape out of the front of the turret in the event of a bailout. Teething troubles with vibration when firing saw the turrets introduction further delayed. However, by May 1944, the turret was ready to be used operationally.

The first squadron to receive the new turret was 101 when two of their Lancasters were fitted with the new installation. However, the turret was not a complete success as the guns suffered from stoppages and were not as reliable as their .303" counterparts.

The new turrets did have a much better field of view and coverage of fire which may account for why Lancasters fitted with the installation suffered fewer attacks. However, it again shows the importance put on 101 Squadron's operations that they were chosen to be equipped with a weapon designed to defend themselves better.

The design consisted of two 0.5" Browning machine guns that offered a greater range and, with a bigger bullet, more destructive power and penetration. It also allowed the gunner to sit on his parachute and escape out of the front of the turret in the event of a bailout. Teething troubles with vibration when firing saw the turrets introduction further delayed. However, by May 1944, the turret was ready to be used operationally.

The first squadron to receive the new turret was 101 when two of their Lancasters were fitted with the new installation. However, the turret was not a complete success as the guns suffered from stoppages and were not as reliable as their .303" counterparts.

The new turrets did have a much better field of view and coverage of fire which may account for why Lancasters fitted with the installation suffered fewer attacks. However, it again shows the importance put on 101 Squadron's operations that they were chosen to be equipped with a weapon designed to defend themselves better.

Centurian Lancasters

While many Lancasters were lucky to see even a small number of operations before being lost, two from 101 Squadron achieved over 100 missions while flying from Ludford Magna. Lancaster III DV245 SR-S, affectionately known as 'The Saint', clocked up one hundred and eighteen operations, including nine trips to Berlin and the raid on Nuremberg. DV245 commenced operations on 7/8 October 1943 with a raid on Stuttgart. On 23/24 February 1945, the Lancaster took part in a raid to Pforzheim when a Me262 jet fighter was spotted by the Air Bomber Fg Off John R Drewery. He promptly manned the front .303 Browning machine guns and fired three bursts at the Luftwaffe fighter. His bullets were seen to hit the Me262, which caught fire and dived towards the ground, where it exploded upon impact. DV245 was lost on its 119th mission, a raid to Bremen on 23 March 1945, which saw the aircraft being the last 101 Squadron Lancaster lost during the war. Despite conflicting accounts, it seems likely the crew were all lost.

The Squadron's second high scoring Lancaster was B.I DV302 SR-H, 'Harry', which undertook 121 operations. Surviving the war, the aircraft was scrapped in January 1947.

While many Lancasters were lucky to see even a small number of operations before being lost, two from 101 Squadron achieved over 100 missions while flying from Ludford Magna. Lancaster III DV245 SR-S, affectionately known as 'The Saint', clocked up one hundred and eighteen operations, including nine trips to Berlin and the raid on Nuremberg. DV245 commenced operations on 7/8 October 1943 with a raid on Stuttgart. On 23/24 February 1945, the Lancaster took part in a raid to Pforzheim when a Me262 jet fighter was spotted by the Air Bomber Fg Off John R Drewery. He promptly manned the front .303 Browning machine guns and fired three bursts at the Luftwaffe fighter. His bullets were seen to hit the Me262, which caught fire and dived towards the ground, where it exploded upon impact. DV245 was lost on its 119th mission, a raid to Bremen on 23 March 1945, which saw the aircraft being the last 101 Squadron Lancaster lost during the war. Despite conflicting accounts, it seems likely the crew were all lost.

The Squadron's second high scoring Lancaster was B.I DV302 SR-H, 'Harry', which undertook 121 operations. Surviving the war, the aircraft was scrapped in January 1947.

The Airfield Today

Today very little remains at RAF Ludford Magna to show what would once have been a hive of activity at one of Lincolnshire's most important Bomber Command airfields. The runways have all but gone, but parts of the perimeter track remain. Small areas of the dispersed site are still in existence, most now in use for purposes very different for which they were designed.

The Thor sites are still in existence but not accessible to the public.

A memorial in the village now stands as a silent witness to 101 Squadron and the sacrifices made by its gallant crews and personnel.

For anyone who wants to know more about what life was like in 101 Squadron while flying from Ludford Magna, the book Carried On The Wind by Sean Feast is a must-read. The book recounts the memories of Flt Lt Ted Manners, who was a Special Operator with 101 and took part in many of the squadron's most daring raids.

Click on images to enlarge.

All images by Richard Hall

The Thor sites are still in existence but not accessible to the public.

A memorial in the village now stands as a silent witness to 101 Squadron and the sacrifices made by its gallant crews and personnel.

For anyone who wants to know more about what life was like in 101 Squadron while flying from Ludford Magna, the book Carried On The Wind by Sean Feast is a must-read. The book recounts the memories of Flt Lt Ted Manners, who was a Special Operator with 101 and took part in many of the squadron's most daring raids.

Click on images to enlarge.

All images by Richard Hall

The following photos show some of the remains that can be seen today.

Sources

- Action Stations 2 - Military Airfields Of Lincolnshire and the East Midlands - Bruce Barrymore Halpenny

- Airfields Of Lincolnshire Since 1912 - Ron Blake - Mike Hodgson - Bill Taylor

- Bomber Command Airfields Of Lincolnshire - Peter Jacobs

- Bases Of Bomber Command Then And Now - Roger A Freeman

- The Source Book Of The RAF - Ken Delve

- Lancaster - The Story Of A Famous Bomber - Bruce Robertson

- 1 Group Swift To Attack - Bomber Command's Unsung Heroes - Patrick Otter

- Royal Air Force Bomber Command Losses Of The Second World War 1943, 1944 & 1945 - W R Chorley