Ashley Walk Bombing Range

Words and photos (unless otherwise specified) by Richard Hall.

The New Forest, located in the South of England, is one of Britain's best known National Parks. It is famous for its ponies and areas of tranquil beauty. With vast areas of tracks and trails, it is a very popular area for those who love the outdoors. Now, if you were told that among all this area of outstanding beauty, there exist the remains of a site that once tested the then most destructive forces known to man, you would quite probably think it was a bit of an old wives tale, well it's all true. Today the former bombing range at Ashley Walk is now back to its former self, where the skylarks ascend to sing their hearts out, and the ponies graze happily. However, if you went back 80 years, it was a far noisier place and not somewhere to go for a casual stroll. The New Forest was an area that contributed much to the Second World War. At one time, there was no less than twelve airfields and advanced landing grounds located within its region, including such well-known names as Hurn, Stoney Cross, Ibsley, Holmsley and Lymington.

On December 4 1939, the New Forest Verderers considered a proposal submitted by the Air Ministry for a bombing range to be built on a temporary basis near Godshill. There was no objection in principle to the proposal for the duration of the war. However, the Verderers asked that the proposed area be fenced off and that it would be made man and pig proof. In due course, a chain-link fence of some 6ft high was erected. There were 13 access points to the range, with the main entrance located on Snake Road. Here there was a small guardroom located adjacent to the main gate. Although pig proof, the area did not deter small boys from entering, and there are tales of the range being a much-used playground during the wartime years by local lads.

The site came into use in mid-1940 and covered some 5,000 acres. It was controlled by the Armaments Squadron of the Aeroplane and Armament Experimental Establishment (A&AEE). Being in a fairly remote area, the personnel who operated the range were billeted in purpose-built huts opposite the Fighting Cocks pub in Godshill. Ashley Walk was an impressive site and had a vast range of facilities. This was just as well as practically every type of air-dropped ordnance used by the RAF (except incendiary weapons) were tested here between 1940 and 1946. Along with this, guns and rockets were also evaluated. The types of bombs dropped ranged from small anti-personnel weapons to the ultimate in air ordnance, the 22,000lb Grand Slam medium-capacity bomb.

The range was divided into two parts, one of which was used for practice. This area had a diameter of 2,000 yards and was used for dropping inert bombs up to a height of 14,000ft. It could be operated by either day or night, and if night bombing was required, the targets could be illuminated with lighting powered by a diesel generator. The area was controlled by a tower located at Hampton Ridge, known as the Main Practice Tower.

The second part was known as the High Explosive Range (HER), and had a diameter of 4,000 yards controlled by the North Tower, located near the road running between Fordingbridge and Cadnam. This area of the range could be used to a height of 20,000ft for the dropping of ordnance. The towers at both locations were approximately 30ft high with large windows, which gave a good view of events out on the ground. The entire site was under the control of the Range Office. In addition, there were two observation huts, one at Amberwood, which still exists to this day and the other, a filming shelter adjoining No 2 Target Wall.

Transport links to the range were by road, but in addition to this, two airstrips were built, both 400 yards long for use by small Auster or Piper type liaison aircraft. The strips ran south and south-west from the southern edge of what is now Godshill cricket pitch.

Targeting Facilities

At the start of the Second World War, the bombs available to the RAF ranged in size from 250 to 2000Ibs. In February 1942, Acting Air Marshal Sir Arthur Harris was appointed as Commander-in-Chief of Bomber Command. Up until that time, the results from the effort expended by the Command in bombing Germany were not reaping the results that had been expected. Harris was brought in to make the Command a more efficient force, something that he did, not without a little (unjust) controversy until the war's end. In his view, the way to defeat Germany was by strategic bombing not only to weaken the country's industrial output but also to reduce civilian morale. Harris was convinced the war could be won from the air without the need for land operations that would be costly in lives to the allied armies. As he put his plans into action, there was a need for ever-larger air-dropped ordnance, as targeting evolved and the need for greater destructive power became apparent. Ashley Walk was at the forefront of aiding the A&AEE in bomb development, delivery methods and techniques. To cater for this, the facilities at the range were required to keep pace with testing needs and a host of targets were built.

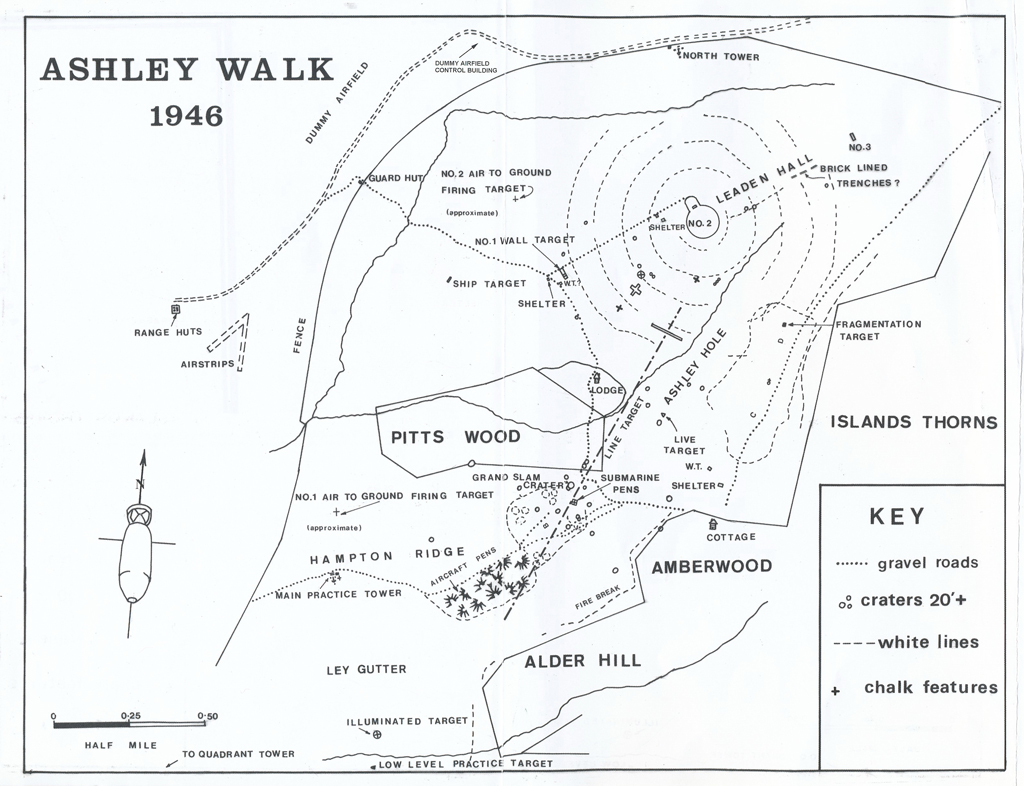

Evidence of many of these targets can still be found on the ground today (more about this later). This is in part due to the fact that the targets were marked by chalk which is alien to the New Forest. The chalk was imported to the range and, when placed, stopped future vegetation from growing back, hence why marked targets can still be clearly seen. Below is a map as the range was in 1946.

(Map - By kind permission of The New Forest Research & Publication Trust)

The New Forest, located in the South of England, is one of Britain's best known National Parks. It is famous for its ponies and areas of tranquil beauty. With vast areas of tracks and trails, it is a very popular area for those who love the outdoors. Now, if you were told that among all this area of outstanding beauty, there exist the remains of a site that once tested the then most destructive forces known to man, you would quite probably think it was a bit of an old wives tale, well it's all true. Today the former bombing range at Ashley Walk is now back to its former self, where the skylarks ascend to sing their hearts out, and the ponies graze happily. However, if you went back 80 years, it was a far noisier place and not somewhere to go for a casual stroll. The New Forest was an area that contributed much to the Second World War. At one time, there was no less than twelve airfields and advanced landing grounds located within its region, including such well-known names as Hurn, Stoney Cross, Ibsley, Holmsley and Lymington.

On December 4 1939, the New Forest Verderers considered a proposal submitted by the Air Ministry for a bombing range to be built on a temporary basis near Godshill. There was no objection in principle to the proposal for the duration of the war. However, the Verderers asked that the proposed area be fenced off and that it would be made man and pig proof. In due course, a chain-link fence of some 6ft high was erected. There were 13 access points to the range, with the main entrance located on Snake Road. Here there was a small guardroom located adjacent to the main gate. Although pig proof, the area did not deter small boys from entering, and there are tales of the range being a much-used playground during the wartime years by local lads.

The site came into use in mid-1940 and covered some 5,000 acres. It was controlled by the Armaments Squadron of the Aeroplane and Armament Experimental Establishment (A&AEE). Being in a fairly remote area, the personnel who operated the range were billeted in purpose-built huts opposite the Fighting Cocks pub in Godshill. Ashley Walk was an impressive site and had a vast range of facilities. This was just as well as practically every type of air-dropped ordnance used by the RAF (except incendiary weapons) were tested here between 1940 and 1946. Along with this, guns and rockets were also evaluated. The types of bombs dropped ranged from small anti-personnel weapons to the ultimate in air ordnance, the 22,000lb Grand Slam medium-capacity bomb.

The range was divided into two parts, one of which was used for practice. This area had a diameter of 2,000 yards and was used for dropping inert bombs up to a height of 14,000ft. It could be operated by either day or night, and if night bombing was required, the targets could be illuminated with lighting powered by a diesel generator. The area was controlled by a tower located at Hampton Ridge, known as the Main Practice Tower.

The second part was known as the High Explosive Range (HER), and had a diameter of 4,000 yards controlled by the North Tower, located near the road running between Fordingbridge and Cadnam. This area of the range could be used to a height of 20,000ft for the dropping of ordnance. The towers at both locations were approximately 30ft high with large windows, which gave a good view of events out on the ground. The entire site was under the control of the Range Office. In addition, there were two observation huts, one at Amberwood, which still exists to this day and the other, a filming shelter adjoining No 2 Target Wall.

Transport links to the range were by road, but in addition to this, two airstrips were built, both 400 yards long for use by small Auster or Piper type liaison aircraft. The strips ran south and south-west from the southern edge of what is now Godshill cricket pitch.

Targeting Facilities

At the start of the Second World War, the bombs available to the RAF ranged in size from 250 to 2000Ibs. In February 1942, Acting Air Marshal Sir Arthur Harris was appointed as Commander-in-Chief of Bomber Command. Up until that time, the results from the effort expended by the Command in bombing Germany were not reaping the results that had been expected. Harris was brought in to make the Command a more efficient force, something that he did, not without a little (unjust) controversy until the war's end. In his view, the way to defeat Germany was by strategic bombing not only to weaken the country's industrial output but also to reduce civilian morale. Harris was convinced the war could be won from the air without the need for land operations that would be costly in lives to the allied armies. As he put his plans into action, there was a need for ever-larger air-dropped ordnance, as targeting evolved and the need for greater destructive power became apparent. Ashley Walk was at the forefront of aiding the A&AEE in bomb development, delivery methods and techniques. To cater for this, the facilities at the range were required to keep pace with testing needs and a host of targets were built.

Evidence of many of these targets can still be found on the ground today (more about this later). This is in part due to the fact that the targets were marked by chalk which is alien to the New Forest. The chalk was imported to the range and, when placed, stopped future vegetation from growing back, hence why marked targets can still be clearly seen. Below is a map as the range was in 1946.

(Map - By kind permission of The New Forest Research & Publication Trust)

Air to Ground Targets: There was two air to ground targets built near the western edge of the High Explosive Range. The targets consisted of yellow and black squares and were used for guns up to 40mm and rockets of 3" diameter.

The Line Target: This consisted of a 10ft wide line of some 2,000 yards in length, terminating with a white marked cross, with arms of 100 yards. The target was created using chalk; its purpose was to simulate a railway line or road and was used to develop ground attack techniques using rockets or bombs.

Wall Targets

No 1 Wall Target: Measuring 40ft wide by 40ft high and constructed of 9in reinforced concrete.

No 2 Wall Target: The same size as above, built on a 9in concrete base 200 yards in diameter. From an aerial view, the target is surrounded by a series of concentric circles formed by bulldozing away the topsoil to reveal the bleached gravel. The circles were used to provide a guide to impact distances.

No 3 Wall Target: Very different to the other two, this was constructed to test bouncing bombs as designed by Dr Barnes Wallis. The wall was 8ft 10in high, 6ft thick, and 20ft long, faced with 2in of armour plate. Initially, the 'Highball' mine was tested, which was carried by a De Havilland Mosquito. In August 1943, the wall was extended in length by 90ft to allow the testing of 'Upkeep'. This was the mine initially used during the famous Dams Raid in May 1943, carried by specially modified Avro Lancasters.

Ship Target: As the name suggests, the target was designed to represent a ship and was located on flat ground at Cockley Plain. The target was constructed from steel plates and heavy angle iron girders. It was used to test the effectiveness and penetrating powers of 20, 40mm cannons, air to ground rockets and the 6 pounder gun used in the Mosquito.

Fragmentation Targets: Two areas on the range were set aside for the testing of fragmentation bombs. The areas were A, B, C and D and marked in chalk with their designated letters, so they were visible from the air.

Fragmentation Targets: Two areas on the range were set aside for the testing of fragmentation bombs. The areas were known as A, B, C and D, and were marked in chalk with their designated letters, so they were visible from the air. Sites A and B were located near Alderman Bottom. A number of aircraft pens were constructed here in line with the design used by the Luftwaffe. The pens themselves would contain time-expired or redundant aircraft, their purpose to show the effects of the various types of ordnance and the protection offered by the enclosure.

Sites C and D were located to the east of Coopers Hill. This area was used to test fragmentation bombs against surface targets such as trenches and command posts. Within the trenches, dummies would be placed, and the results of the ordnance used against these evaluated to gauge its effectiveness.

Ministry of Home Security Target (Submarine Pen): This target presents something of a mystery. Some say it was built to represent a U-Boat pen as located on the French Atlantic coast. However, recently released records also give credence to the target structure being designed to test the effects of explosives with a view to developing more resilient public air raid shelters.

The theory of it being a mock submarine pen does hold water (excuse the pun), though. When it became evident that the Germans were building substantial concrete structures on the French Coast to house their U-Boats, the RAF were keen to destroy them but needed to evaluate how they could be best penetrated. To simulate the structures, a replica was built at Ashley Walk in September 1941 at the cost of £250,000. A vast concrete raft 6ft thick and measuring 79ft by 70ft was constructed. Supported on five walls, 6ft high, the structure was built on a foundation 20in thick. The outer walls were 3ft in thick with inner walls of 1ft 9in.

The RAF tried many times to destroy the pen but were not successful, as the bombs used at the time, were in reality, relatively small to make an impression on such a massively constructed structure. As a result, it would not be until later in the war that the RAF managed to penetrate the submarine pens in France. To do this, 12,000Ib Tallboy and 22,000lb Grand Slam bombs were used.

Improving Accuracy

Throughout the tests conducted at Ashley, bombing accuracy was constantly improving. An anecdote from the time goes as follows. A film of an inert bomb approaching a target was required. It was considered that the safest place to put the camera was the target centre. This cynical approach cost the Ministry one cine camera after the bomb hit the target centre fair and square.

Testing of Highball and Upkeep

The story of the Wallis designed Upkeep mine as used by the Dambusters in May 1943 (Operation Chastise) is well known, but that of its smaller sibling, Highball, is not. On 2 April 1943, a directive was issued from the Headquarters of Coastal Command entitled Operation Highball. This was the name given to a special mining weapon, together with the training and the exercises that accompanied the project. The unit responsible for the testing and development of the munition was 618 Squadron equipped with De Havilland Mosquito IVs, which formed at RAF Skitten (satellite to RAF Wick) as part of 18 Group, under the command of Wg Cdr G H B Hutchinson.

The unit's ORB states the following: 'The squadron was formed for the purpose of attacking the German Fleet in Norway, with a weapon that is still in its final stages of development. To coincide the operational employment of the weapon Highball with that of a Bomber Command Squadron equipped with a somewhat similar weapon, a target date of 15 May 1943, was agreed upon. Intensive training had to be undertaken on a type of aircraft familiar to a percentage only of the squadron and the crews had to become proficient in the handling of the weapon. In order to direct the operation against the main prize of the German Fleet, the Tirpitz, which was lying safe and unscathed in Alten Fjord in Norway, Sumburgh was chosen as the base from which the attack would commence and preparations to that end proceeded apace'. (Note: the proposed attack on the Tirpitz was known as Operation Servant)

'The weapon itself consists of a spherical depth charge, spun backwards at nearly 1,000 rpm and released from the wall in the fuselage of the aircraft at sea level. The spin causes the sphere (or store) to bounce on impact with the water and to continue bouncing for distances of up to 1,500 yards or so, thus avoiding any attempt to hinder its progress by anti-mine booms and netting. On striking the target, the store rebounds, falls into the water still spinning, curves underwater underneath the ship and is exploded by hydrostatic pistols at preselected depths. From the fact that the charge consists of 600Ibs of Torpex and that the explosion is liable to take place under the belly of the ship behind the outer armoured belt, incredible prospects lay ahead of the invention'.

Initial testing was planned to take place on Loch Striven in Scotland, but poor weather prevailed, so it was decided to use Ashley Walk, where the steel-faced No 3 Wall Target was erected to facilitate the trials. Contemporary footage from April 1943 shows the low-level approach of a Mosquito across the range and the release of the inert mine, which is seen skipping across the land until making a rather spectacular contact with a small hut-like structure. It is somewhat alarming to see how near range personnel were standing to the point of impact when the Highball hits its intended target. Also shown is the evasive action the Mosquito had to take to avoid the earth thrown up when the mine impacted the ground just after release.

The ORB goes on to state: 'Trials were undertaken at Ashley Walk against the armoured wall testing ground with the store in a new case and with an aerated resin filling. The stores stood up to the impact more successfully and appeared generally stronger'.

Consideration was given to utilising Highball for attacks on canals, dry docks, submarine pens and railway tunnels, but due to development problems, the mine was never deployed operationally. It was decided to use the munitions manufactured as depth charges, but this too did not come to fruition as 618 Squadron were grounded on 13 September 1943. The plan was for the unit to await the time when Highball was satisfactorily developed to be used in service, but that day never came. Crews from 618 went on to fly with other Coastal Command squadrons, where they took part in operations against U-Boats and shipping. In July 1944, 618 came back together for operations in the Far East, but as with Highball, they did not see any operational service.

Contemporary film footage of the testing at Ashley Walk can be found by accessing the following link - www.youtube.com

The Line Target: This consisted of a 10ft wide line of some 2,000 yards in length, terminating with a white marked cross, with arms of 100 yards. The target was created using chalk; its purpose was to simulate a railway line or road and was used to develop ground attack techniques using rockets or bombs.

Wall Targets

No 1 Wall Target: Measuring 40ft wide by 40ft high and constructed of 9in reinforced concrete.

No 2 Wall Target: The same size as above, built on a 9in concrete base 200 yards in diameter. From an aerial view, the target is surrounded by a series of concentric circles formed by bulldozing away the topsoil to reveal the bleached gravel. The circles were used to provide a guide to impact distances.

No 3 Wall Target: Very different to the other two, this was constructed to test bouncing bombs as designed by Dr Barnes Wallis. The wall was 8ft 10in high, 6ft thick, and 20ft long, faced with 2in of armour plate. Initially, the 'Highball' mine was tested, which was carried by a De Havilland Mosquito. In August 1943, the wall was extended in length by 90ft to allow the testing of 'Upkeep'. This was the mine initially used during the famous Dams Raid in May 1943, carried by specially modified Avro Lancasters.

Ship Target: As the name suggests, the target was designed to represent a ship and was located on flat ground at Cockley Plain. The target was constructed from steel plates and heavy angle iron girders. It was used to test the effectiveness and penetrating powers of 20, 40mm cannons, air to ground rockets and the 6 pounder gun used in the Mosquito.

Fragmentation Targets: Two areas on the range were set aside for the testing of fragmentation bombs. The areas were A, B, C and D and marked in chalk with their designated letters, so they were visible from the air.

Fragmentation Targets: Two areas on the range were set aside for the testing of fragmentation bombs. The areas were known as A, B, C and D, and were marked in chalk with their designated letters, so they were visible from the air. Sites A and B were located near Alderman Bottom. A number of aircraft pens were constructed here in line with the design used by the Luftwaffe. The pens themselves would contain time-expired or redundant aircraft, their purpose to show the effects of the various types of ordnance and the protection offered by the enclosure.

Sites C and D were located to the east of Coopers Hill. This area was used to test fragmentation bombs against surface targets such as trenches and command posts. Within the trenches, dummies would be placed, and the results of the ordnance used against these evaluated to gauge its effectiveness.

Ministry of Home Security Target (Submarine Pen): This target presents something of a mystery. Some say it was built to represent a U-Boat pen as located on the French Atlantic coast. However, recently released records also give credence to the target structure being designed to test the effects of explosives with a view to developing more resilient public air raid shelters.

The theory of it being a mock submarine pen does hold water (excuse the pun), though. When it became evident that the Germans were building substantial concrete structures on the French Coast to house their U-Boats, the RAF were keen to destroy them but needed to evaluate how they could be best penetrated. To simulate the structures, a replica was built at Ashley Walk in September 1941 at the cost of £250,000. A vast concrete raft 6ft thick and measuring 79ft by 70ft was constructed. Supported on five walls, 6ft high, the structure was built on a foundation 20in thick. The outer walls were 3ft in thick with inner walls of 1ft 9in.

The RAF tried many times to destroy the pen but were not successful, as the bombs used at the time, were in reality, relatively small to make an impression on such a massively constructed structure. As a result, it would not be until later in the war that the RAF managed to penetrate the submarine pens in France. To do this, 12,000Ib Tallboy and 22,000lb Grand Slam bombs were used.

Improving Accuracy

Throughout the tests conducted at Ashley, bombing accuracy was constantly improving. An anecdote from the time goes as follows. A film of an inert bomb approaching a target was required. It was considered that the safest place to put the camera was the target centre. This cynical approach cost the Ministry one cine camera after the bomb hit the target centre fair and square.

Testing of Highball and Upkeep

The story of the Wallis designed Upkeep mine as used by the Dambusters in May 1943 (Operation Chastise) is well known, but that of its smaller sibling, Highball, is not. On 2 April 1943, a directive was issued from the Headquarters of Coastal Command entitled Operation Highball. This was the name given to a special mining weapon, together with the training and the exercises that accompanied the project. The unit responsible for the testing and development of the munition was 618 Squadron equipped with De Havilland Mosquito IVs, which formed at RAF Skitten (satellite to RAF Wick) as part of 18 Group, under the command of Wg Cdr G H B Hutchinson.

The unit's ORB states the following: 'The squadron was formed for the purpose of attacking the German Fleet in Norway, with a weapon that is still in its final stages of development. To coincide the operational employment of the weapon Highball with that of a Bomber Command Squadron equipped with a somewhat similar weapon, a target date of 15 May 1943, was agreed upon. Intensive training had to be undertaken on a type of aircraft familiar to a percentage only of the squadron and the crews had to become proficient in the handling of the weapon. In order to direct the operation against the main prize of the German Fleet, the Tirpitz, which was lying safe and unscathed in Alten Fjord in Norway, Sumburgh was chosen as the base from which the attack would commence and preparations to that end proceeded apace'. (Note: the proposed attack on the Tirpitz was known as Operation Servant)

'The weapon itself consists of a spherical depth charge, spun backwards at nearly 1,000 rpm and released from the wall in the fuselage of the aircraft at sea level. The spin causes the sphere (or store) to bounce on impact with the water and to continue bouncing for distances of up to 1,500 yards or so, thus avoiding any attempt to hinder its progress by anti-mine booms and netting. On striking the target, the store rebounds, falls into the water still spinning, curves underwater underneath the ship and is exploded by hydrostatic pistols at preselected depths. From the fact that the charge consists of 600Ibs of Torpex and that the explosion is liable to take place under the belly of the ship behind the outer armoured belt, incredible prospects lay ahead of the invention'.

Initial testing was planned to take place on Loch Striven in Scotland, but poor weather prevailed, so it was decided to use Ashley Walk, where the steel-faced No 3 Wall Target was erected to facilitate the trials. Contemporary footage from April 1943 shows the low-level approach of a Mosquito across the range and the release of the inert mine, which is seen skipping across the land until making a rather spectacular contact with a small hut-like structure. It is somewhat alarming to see how near range personnel were standing to the point of impact when the Highball hits its intended target. Also shown is the evasive action the Mosquito had to take to avoid the earth thrown up when the mine impacted the ground just after release.

The ORB goes on to state: 'Trials were undertaken at Ashley Walk against the armoured wall testing ground with the store in a new case and with an aerated resin filling. The stores stood up to the impact more successfully and appeared generally stronger'.

Consideration was given to utilising Highball for attacks on canals, dry docks, submarine pens and railway tunnels, but due to development problems, the mine was never deployed operationally. It was decided to use the munitions manufactured as depth charges, but this too did not come to fruition as 618 Squadron were grounded on 13 September 1943. The plan was for the unit to await the time when Highball was satisfactorily developed to be used in service, but that day never came. Crews from 618 went on to fly with other Coastal Command squadrons, where they took part in operations against U-Boats and shipping. In July 1944, 618 came back together for operations in the Far East, but as with Highball, they did not see any operational service.

Contemporary film footage of the testing at Ashley Walk can be found by accessing the following link - www.youtube.com

|

Highball was not the last of Wallis's mines tested at Ashley Walk. In early August 1943, five 617 Squadron Lancasters flew from Scampton to Boscombe Down in readiness to undertake tests of forward rotating Upkeep mines at the range. This was to establish if the weapon could be used across ground as opposed to water.

It is of note that some of the aircraft that took part in Operation Chastise on 16/17 May 1943 would now be releasing their mines in the heart of the New Forest. |

The pilots for the initial trial from the best available evidence were Flt Lts D J Shannon, W H Kellaway, D J H Maltby, Flt Sgt K W Brown and Fg Off Clayton. Shannon and Maltby had flown in Wave 1 with Wg Cdr Guy Gibson during Chastise and had released their Upkeep mines against the Mohne and Eder Dams, which were successfully breached. Brown had taken part in Wave 3 and attacked the Sorpe Dam, which remained intact with slight damage to the crest.

Within the squadron Operations Record Book (ORB), the deployment to Boscombe is described as 'tactical exercises', but the true purpose was to establish if the mine could be used to breach defences on the French coast, in anticipation of its potential use in the forthcoming invasion of Europe. Note: There is also some indication thought had been given to use Upkeep against viaducts in the Ruhr.

On 5 August 1943, the five Lancasters flew in line astern across the range to release their mines at low level, but the air became turbulent. This disturbance was to have a negative impact on one of their number. Lancaster III Type 464 Provisioning ED765 AJ-M had been the first to be modified to carry Upkeep and was flown by 617 Squadron for trial work. On the day of the test, Kellaway piloting the Lancaster was the last in line to run into the target. As he did so, the aircraft was caught in the slipstream of the one proceeding. In a steep turn over Deadman's Bottom, Kellaway fought for control which put him on course to collide with pylons on Turf Hill. He tried to fly under them, but in doing so, the bomber's port wingtip clipped the ground, and a crash ensued. Although there were injuries to the crew, they were all extremely fortunate to survive. The wrecked Lancaster caused a problem for the range personnel as being marked with the suffix 'G' denoted it as secret and that it was to be guarded at all times. Until salvage could be undertaken, the wreck was watched over by members of the RAF Regiment who came from nearby RAF Stoney Cross.

The tests continued on 12 August 1943 without further incident, with Plt Off W G Divall and Flt Lt R A P Allsebrook participating in place of Kellaway and Clayton. However, it is unclear if Maltby took part in the trial as his logbook states on the day that, although he was flying from Boscombe Down, he was piloting Lancaster EE131, which was not modified to carry Upkeep.

It is sad to reflect Maltby, Allsebrook and Divall were lost with their crews on 15 September 1943, when 617 Squadron carried out an operation to the Dortmund-Ems Canal. As with Highball, Upkeep was not to see any further use during the war. The remaining mines were disposed of in Operation Guzzle after the conclusion of the conflict.

Within the squadron Operations Record Book (ORB), the deployment to Boscombe is described as 'tactical exercises', but the true purpose was to establish if the mine could be used to breach defences on the French coast, in anticipation of its potential use in the forthcoming invasion of Europe. Note: There is also some indication thought had been given to use Upkeep against viaducts in the Ruhr.

On 5 August 1943, the five Lancasters flew in line astern across the range to release their mines at low level, but the air became turbulent. This disturbance was to have a negative impact on one of their number. Lancaster III Type 464 Provisioning ED765 AJ-M had been the first to be modified to carry Upkeep and was flown by 617 Squadron for trial work. On the day of the test, Kellaway piloting the Lancaster was the last in line to run into the target. As he did so, the aircraft was caught in the slipstream of the one proceeding. In a steep turn over Deadman's Bottom, Kellaway fought for control which put him on course to collide with pylons on Turf Hill. He tried to fly under them, but in doing so, the bomber's port wingtip clipped the ground, and a crash ensued. Although there were injuries to the crew, they were all extremely fortunate to survive. The wrecked Lancaster caused a problem for the range personnel as being marked with the suffix 'G' denoted it as secret and that it was to be guarded at all times. Until salvage could be undertaken, the wreck was watched over by members of the RAF Regiment who came from nearby RAF Stoney Cross.

The tests continued on 12 August 1943 without further incident, with Plt Off W G Divall and Flt Lt R A P Allsebrook participating in place of Kellaway and Clayton. However, it is unclear if Maltby took part in the trial as his logbook states on the day that, although he was flying from Boscombe Down, he was piloting Lancaster EE131, which was not modified to carry Upkeep.

It is sad to reflect Maltby, Allsebrook and Divall were lost with their crews on 15 September 1943, when 617 Squadron carried out an operation to the Dortmund-Ems Canal. As with Highball, Upkeep was not to see any further use during the war. The remaining mines were disposed of in Operation Guzzle after the conclusion of the conflict.

|

For many years after the testing of Upkeep, parts of the mines were left where they fell. In the early 1970s, permission was given to members of 14 Group (Winchester) Royal Observer Corps (ROC) to retrieve some of the remaining pieces from the range. The parts obtained allowed for the restoration by ROC officer Norman Parker of one complete Upkeep. On 18 May 1975, at a ceremony held at Middle Wallop with Barnes Wallis and Dambuster pilots Dave Shannon and Geoff Rice in attendance, the restored Upkeep was presented at a special ROC event to OC 617 Squadron Wg Cdr V Warrington.

|

The mine was then taken to Scampton, where contemporary photos show it on display with two of Wallis's other designs, Tallboy and Grand Slam, near to then gate guardian Lancaster VII NX611. This aircraft now resides at the Lincolnshire Aviation Heritage Centre, East Kirkby. The three munitions continue at this time to remain onsite at 617's Squadron's former home.

Testing of the Earthquake Bombs

|

The largest air dropped conventional ordnance used during the war were the 12,000lb Tallboy and the 22,000Ib Grand Slam bombs. Both were designed by Barnes Wallis and were known as 'earthquake' bombs. There is a good reason for the name, as when they landed and detonated, they caused a condition similar to an earthquake. Both types of bomb were tested at Ashley Walk.

The Tallboy and Grand Slams were deep penetration bombs with streamlined casings made from high-quality steel with specially hardened nose sections. |

The Tallboy was stabilised in flight by four fins inclined at an angle of 5 degrees, which caused the bomb to spin about its axis as it fell. Initially, inert examples were dropped into the range, but five later drops used ordnance filled with 5,200Ib of Torpex. The bombs were delivered by Avro Lancasters of 617 Squadron, the design of the aircraft allowing the dropping of such large weapons.

The first live trial of a Tallboy took place at the range on 18 April 1944. Scheduled for the morning, the test was delayed due to poor weather and went ahead at 18.00hrs. Four small practice bombs were dropped by a Lancaster to check for accuracy, followed by two dummy runs. Finally, on the third run at a speed of 169 mph and at a height of 18,000ft, the first live Tallboy was released. The bomb landed 100 yards from the target, with the sound of the munition falling, reaching observers seconds after the impact. After a short delay, earth and flame were thrown up as the bomb detonated. It had taken 37 seconds from release to impact, with a terminal velocity of 1,000ft per second reached.

The crater created by the Tallboy was 92ft in diameter and was almost perfectly circular. The crater's depth was between 20ft to 30ft deep, and it is estimated the bomb penetrated to a depth of 60ft. On the same day, a second Tallboy was dropped with results similar to that of the first. The trials were thought a success, and it was considered that the Tallboy would be a good weapon to use against rigid targets due to its ability to create a localised earthquake sufficient to weaken structures.

Further tests took place on 24 and 25 April; six Tallboys were dropped by a Lancaster with Flt Lt Asbury DFC (RAAF) in the nose acting as bomb aimer. The bomb's designer Wallis considered that a direct hit would penetrate the target, while a near miss would cause severe disruption.

The bombs were dropped from 18,000ft in clear weather, with the following results being achieved –

1. Crater 80ft (sand) Depth 11ft 8in Distance from Aiming Point 106 yards

2. Crater 75ft (clay) Depth 10ft 8in Distance from Aiming Point 302 yards

3. Crater 66ft (clay) Depth 21ft Distance from Aiming Point 150 yards

4. Crater 84ft (sand) Depth 19ft 3in Distance from Aiming Point 107 yards

5. Crater 89ft (sand) Depth 18ft Distance from Aiming Point 84 yards

6. Crater 80ft (clay) Depth 17ft Distance from Aiming Point 83 yards

Continued testing of Tallboy took place at Ashley Walk on 11 May 1944 when two more were dropped to provide fuzing data. The first operational use of Tallboy occurred on 8/9 June 1944, when 617 Squadron Lancasters successfully bombed and blocked the railway tunnel at Saumur, France. The operation also included the use of four Lancasters from 83 Squadron who provided clusters of flares (and their own bomb loads) to aid Wg Cdr L Cheshire (flying Mosquito VI MS993) in locating the tunnel mouth so that he could use spot flares to mark it for the attacking force. The blocking of the tunnel was crucial in aiding the recent invasion of Normandy, as it denied the Germans the use of a railway that was vital in transporting men and equipment from south-western France to the new front.

Tallboy was a valuable asset to the RAF's weapons inventory, and a second unit, 9 Squadron based at RAF Bardney, were also equipped to carry the munition. Both 9 and 617 Squadrons went on to attack a number of high-value targets, including U-Boat pens, canals, viaducts, the battleship Tirpitz and even Hitler's Berghof. By the war's end, 854 of Wallis's deep penetration bomb had been dropped.

The crater created by the Tallboy was 92ft in diameter and was almost perfectly circular. The crater's depth was between 20ft to 30ft deep, and it is estimated the bomb penetrated to a depth of 60ft. On the same day, a second Tallboy was dropped with results similar to that of the first. The trials were thought a success, and it was considered that the Tallboy would be a good weapon to use against rigid targets due to its ability to create a localised earthquake sufficient to weaken structures.

Further tests took place on 24 and 25 April; six Tallboys were dropped by a Lancaster with Flt Lt Asbury DFC (RAAF) in the nose acting as bomb aimer. The bomb's designer Wallis considered that a direct hit would penetrate the target, while a near miss would cause severe disruption.

The bombs were dropped from 18,000ft in clear weather, with the following results being achieved –

1. Crater 80ft (sand) Depth 11ft 8in Distance from Aiming Point 106 yards

2. Crater 75ft (clay) Depth 10ft 8in Distance from Aiming Point 302 yards

3. Crater 66ft (clay) Depth 21ft Distance from Aiming Point 150 yards

4. Crater 84ft (sand) Depth 19ft 3in Distance from Aiming Point 107 yards

5. Crater 89ft (sand) Depth 18ft Distance from Aiming Point 84 yards

6. Crater 80ft (clay) Depth 17ft Distance from Aiming Point 83 yards

Continued testing of Tallboy took place at Ashley Walk on 11 May 1944 when two more were dropped to provide fuzing data. The first operational use of Tallboy occurred on 8/9 June 1944, when 617 Squadron Lancasters successfully bombed and blocked the railway tunnel at Saumur, France. The operation also included the use of four Lancasters from 83 Squadron who provided clusters of flares (and their own bomb loads) to aid Wg Cdr L Cheshire (flying Mosquito VI MS993) in locating the tunnel mouth so that he could use spot flares to mark it for the attacking force. The blocking of the tunnel was crucial in aiding the recent invasion of Normandy, as it denied the Germans the use of a railway that was vital in transporting men and equipment from south-western France to the new front.

Tallboy was a valuable asset to the RAF's weapons inventory, and a second unit, 9 Squadron based at RAF Bardney, were also equipped to carry the munition. Both 9 and 617 Squadrons went on to attack a number of high-value targets, including U-Boat pens, canals, viaducts, the battleship Tirpitz and even Hitler's Berghof. By the war's end, 854 of Wallis's deep penetration bomb had been dropped.

|

Following on from the Tallboy, things got even bigger with the introduction of the Grand Slam (known initially as Tallboy Large). The bomb's development had been stopped in September 1944 as it was considered that the war would be over by Christmas.

However, after the failure of Operation Market Garden, development was resumed. It was also felt that although the Tallboy was a very effective weapon, some shortcomings had come to light, and a still bigger bomb was required. |

Grand Slam was the largest non-nuclear air-dropped weapon used in the war and was the culmination of five years of Wallis's work. Weighing in at 22,000Ib, this bomb was essentially the same as the Tallboy and carried 9,135Ib of Torpex and was so large that specially designed Lancasters were required to carry the weapon. Known as the B.1 Special, the first two examples came off Woodford's production line in February 1945 with serials PB995 and PB592/G. The two aircraft were sent to A&AEE, where they commenced testing. To save weight, the machines were devoid of front and mid-upper turrets and many other items of equipment usually found on a Lancaster, including bomb doors.

To prove the effectiveness of the new bomb, it was decided, like its smaller brother Tallboy, to test Grand Slam against the concrete target at Ashley Walk. Bad weather during early March 1945 curtailed the first drop, but on 13 March 1945, Lancaster B.1 Special PB592/G from A&AEE flying at 18,000ft above Sandy Balls, released a live Grand Slam, which impacted near Pitts Wood. On the ground, the event was watched by a large group of people, including its designer Wallis. The bomb buried itself deep into the ground and, after a delay of nine seconds, exploded, producing a crater of 34ft deep by 124ft in diameter. There is some evidence that the inhabitants of local villages did not have prior warning of the live test. If this were the case, on this particular Tuesday, the earth would undoubtedly have moved. Only one Grand Slam was evaluated at Ashley Walk as its high cost of production precluded further testing. In reality, there was no need to anyway as it was shown what the bomb could do. A call to Woodhall Spa was made, and a message passed that the weapon had worked perfectly. Official clearance to use Grand Slam did not come until 22 March 1945, but it would appear that C Flight of 617 Squadron couldn't wait to try out its new ordnance.

On the same day as the test Gp Capt J E Fauquier and Sqn Ldr C C Calder piloting PD112 YZ-S and PD119 YZ-J respectively, took off from Woodhall Spa with Grand Slams aboard and flew to Bielefeld, near Munster, intending to take down the railway viaduct. The structure to date had led a charmed life and had defied all efforts to bring about its destruction. Accompanying the B.1 Specials were Tallboy carrying Lancasters, but the operation was frustrated by poor weather, and bombing was impossible. The raiding force brought back their precious cargos with Fauquier and Calder landing with the war's heaviest bomb onboard at Carnaby, an alternate airfield chosen for its long runway. Of note, the squadron's ORB states all aircraft carried Tallboys on this operation. Also, on this day, 9 Squadron attacked the Arnsberg Viaduct in the North Rhine – Westphalia region of Germany, but again the weather was unfavourable, and only two Lancasters released their loads.

The next day the operation was back on. Although hazy, this time, the weather allowed Lancasters of 9 and 617 Squadrons to complete their attacks on the two viaducts. The B.1 Specials were still at Carnaby, and it was from here that Calder took off, leaving Fauquier (PD119) behind as his Stabilised Automatic Bombsight went unserviceable. Calder had noted his boss's predicament, and sensing he would try and requisition his Lancaster, he ignored the C/O's gesticulations and took off, much to the senior officer's anger.

At 16.28hrs, from 11,965ft, Flt Lt C Crafer, the bomb aimer onboard Lancaster B.I (Special), PD112, piloted by Calder dropped his Grand Slam at Bielefeld. The result, 100 yards of the viaduct collapsing due to the earthquake effect of the ordnance. Within the unit's ORB, the munition is detailed as a 'Special Store'. The Arnsberg viaduct was later found to be undamaged.

The Arnsberg viaduct's luck ran out on 19 March 1945, when 617 Squadron attacked with six Grand Slams, which sealed its fate with a 40ft gap blown in the structure. In total, 41 of the weapons were dropped by 617 Squadron Lancasters before the war ended.

To prove the effectiveness of the new bomb, it was decided, like its smaller brother Tallboy, to test Grand Slam against the concrete target at Ashley Walk. Bad weather during early March 1945 curtailed the first drop, but on 13 March 1945, Lancaster B.1 Special PB592/G from A&AEE flying at 18,000ft above Sandy Balls, released a live Grand Slam, which impacted near Pitts Wood. On the ground, the event was watched by a large group of people, including its designer Wallis. The bomb buried itself deep into the ground and, after a delay of nine seconds, exploded, producing a crater of 34ft deep by 124ft in diameter. There is some evidence that the inhabitants of local villages did not have prior warning of the live test. If this were the case, on this particular Tuesday, the earth would undoubtedly have moved. Only one Grand Slam was evaluated at Ashley Walk as its high cost of production precluded further testing. In reality, there was no need to anyway as it was shown what the bomb could do. A call to Woodhall Spa was made, and a message passed that the weapon had worked perfectly. Official clearance to use Grand Slam did not come until 22 March 1945, but it would appear that C Flight of 617 Squadron couldn't wait to try out its new ordnance.

On the same day as the test Gp Capt J E Fauquier and Sqn Ldr C C Calder piloting PD112 YZ-S and PD119 YZ-J respectively, took off from Woodhall Spa with Grand Slams aboard and flew to Bielefeld, near Munster, intending to take down the railway viaduct. The structure to date had led a charmed life and had defied all efforts to bring about its destruction. Accompanying the B.1 Specials were Tallboy carrying Lancasters, but the operation was frustrated by poor weather, and bombing was impossible. The raiding force brought back their precious cargos with Fauquier and Calder landing with the war's heaviest bomb onboard at Carnaby, an alternate airfield chosen for its long runway. Of note, the squadron's ORB states all aircraft carried Tallboys on this operation. Also, on this day, 9 Squadron attacked the Arnsberg Viaduct in the North Rhine – Westphalia region of Germany, but again the weather was unfavourable, and only two Lancasters released their loads.

The next day the operation was back on. Although hazy, this time, the weather allowed Lancasters of 9 and 617 Squadrons to complete their attacks on the two viaducts. The B.1 Specials were still at Carnaby, and it was from here that Calder took off, leaving Fauquier (PD119) behind as his Stabilised Automatic Bombsight went unserviceable. Calder had noted his boss's predicament, and sensing he would try and requisition his Lancaster, he ignored the C/O's gesticulations and took off, much to the senior officer's anger.

At 16.28hrs, from 11,965ft, Flt Lt C Crafer, the bomb aimer onboard Lancaster B.I (Special), PD112, piloted by Calder dropped his Grand Slam at Bielefeld. The result, 100 yards of the viaduct collapsing due to the earthquake effect of the ordnance. Within the unit's ORB, the munition is detailed as a 'Special Store'. The Arnsberg viaduct was later found to be undamaged.

The Arnsberg viaduct's luck ran out on 19 March 1945, when 617 Squadron attacked with six Grand Slams, which sealed its fate with a 40ft gap blown in the structure. In total, 41 of the weapons were dropped by 617 Squadron Lancasters before the war ended.

Recently some tests have been undertaken at Ashley Walk, where the Grand Slam was dropped. This link gives some further information:

Grand Slam Ashley Walk Investigation

With the end of the war coming in August 1945, Ashley Walk closed in the following year. However, before the range could be handed back, there was a need to clear the area of live ordnance. It would appear that this took some time to achieve, as the Verderers were not informed until 24 July 1948 that it was free from explosives.

Grand Slam Ashley Walk Investigation

With the end of the war coming in August 1945, Ashley Walk closed in the following year. However, before the range could be handed back, there was a need to clear the area of live ordnance. It would appear that this took some time to achieve, as the Verderers were not informed until 24 July 1948 that it was free from explosives.

What Remains on the Ground Today

Map - OS Explorer OL22 New Forest

Note : OS Grid References are given where known to mark the location of remains.

Ashley Walk today is a quiet place with acres of beautiful Hampshire countryside just waiting to be explored by anyone who enjoys a good walk and wants to find a piece of local history. The sounds of the Rolls-Royce Merlin and Bristol Hercules are long gone. However, evidence of the wartime activities is easy to find, although some remains are less obvious. The following should give the reader a good idea of what is to be discovered on the ground. Anyone going to the range is advised to look at Google Earth (GE) as an aerial view shows up what sometimes can be challenging to find on the ground. For example, if you type - 50 56 23 26 N 1 42 32 75 W into the GE search box, it will take you to No 2 Target Wall. The rest of what can be seen is quite evident from this viewpoint. Visitors should be aware that occasionally live ordnance is still unearthed on the range, and care should be exercised if anything suspicious does come to the surface.

Map - OS Explorer OL22 New Forest

Note : OS Grid References are given where known to mark the location of remains.

Ashley Walk today is a quiet place with acres of beautiful Hampshire countryside just waiting to be explored by anyone who enjoys a good walk and wants to find a piece of local history. The sounds of the Rolls-Royce Merlin and Bristol Hercules are long gone. However, evidence of the wartime activities is easy to find, although some remains are less obvious. The following should give the reader a good idea of what is to be discovered on the ground. Anyone going to the range is advised to look at Google Earth (GE) as an aerial view shows up what sometimes can be challenging to find on the ground. For example, if you type - 50 56 23 26 N 1 42 32 75 W into the GE search box, it will take you to No 2 Target Wall. The rest of what can be seen is quite evident from this viewpoint. Visitors should be aware that occasionally live ordnance is still unearthed on the range, and care should be exercised if anything suspicious does come to the surface.

Bomb Craters

Bomb craters are still very evident today and parts of the range resemble a lunar landscape. The main area is littered with these, many resembling small ponds full of water, some provide a habitat where Damselflies now flourish.

Grid Reference SU 2019 1550

Bomb craters are still very evident today and parts of the range resemble a lunar landscape. The main area is littered with these, many resembling small ponds full of water, some provide a habitat where Damselflies now flourish.

Grid Reference SU 2019 1550

Chalk

Chalk is still much in evidence even after all these years of closure. Today where the chalk was used native plants will not grow, this helped to ensure the target markers have not become overgrown. Grid Reference SU 1977 1525

Chalk is still much in evidence even after all these years of closure. Today where the chalk was used native plants will not grow, this helped to ensure the target markers have not become overgrown. Grid Reference SU 1977 1525

The Line Target

The Line Target is still very much in evidence although it does get a little difficult to trace after it has passed over the Ministry of Home Security Target. The target’s termination is easily identifiable as a large white cross again marked by chalk. In its early stages the target resembles a long straight footpath cutting across the range.

Grid Reference SU 1995 1396

The Line Target is still very much in evidence although it does get a little difficult to trace after it has passed over the Ministry of Home Security Target. The target’s termination is easily identifiable as a large white cross again marked by chalk. In its early stages the target resembles a long straight footpath cutting across the range.

Grid Reference SU 1995 1396

The cross centre at the termination of the Line Target - Grid Reference SU 2041 1505

Wall Targets

With all the Wall Targets there is no effective way to photograph the remains in a way that gives much meaning. Therefore, I have listed the Grid References and explained what can be seen on the ground.

No 1 Wall Target

Not much evidence can be seen of this target at ground level, however, from GE its base impression can still be discerned on the ground. Grid Reference SU 1983 1532

No 2 Wall Target

This now appears on the ground as a large circle that looks out of place to its surroundings. Again GE shows the target very clearly as a large sand coloured disk. The target is very large and there is no effective way to photograph it from ground level. Grid Reference SU 2052 1565

No 3 Wall Target

This now appears only as a long low mound of earth. There are thorn bushes growing on it and evidence of rubble. It is understood that the wall was undermined along its length and then simply pushed over and buried.

Ship Target

The remains of this target are visible in the form of a concrete base and foundations with metal bolts still in place.

Grid Reference SU 1927 1522

With all the Wall Targets there is no effective way to photograph the remains in a way that gives much meaning. Therefore, I have listed the Grid References and explained what can be seen on the ground.

No 1 Wall Target

Not much evidence can be seen of this target at ground level, however, from GE its base impression can still be discerned on the ground. Grid Reference SU 1983 1532

No 2 Wall Target

This now appears on the ground as a large circle that looks out of place to its surroundings. Again GE shows the target very clearly as a large sand coloured disk. The target is very large and there is no effective way to photograph it from ground level. Grid Reference SU 2052 1565

No 3 Wall Target

This now appears only as a long low mound of earth. There are thorn bushes growing on it and evidence of rubble. It is understood that the wall was undermined along its length and then simply pushed over and buried.

Ship Target

The remains of this target are visible in the form of a concrete base and foundations with metal bolts still in place.

Grid Reference SU 1927 1522

On my visit the odd piece of metal plate was also visible on the ground.

Fragmentation Targets

Grid Reference A and B Target Area - SU 1964 1136

Grid Reference C and D Target Area - SU 2085 1467

All of the letters A, B, C and D can still be seen on the ground although you need a GPS device to effectively find some of them. The photo below shows Target C

Grid Reference A and B Target Area - SU 1964 1136

Grid Reference C and D Target Area - SU 2085 1467

All of the letters A, B, C and D can still be seen on the ground although you need a GPS device to effectively find some of them. The photo below shows Target C

Ministry of Home Security Target

The remains of this are still very much in evidence as a large mound of earth that covers the concrete structure. It was massively built, and demolition was not considered an option after the war, therefore the target was simply covered over with earth. Concrete is starting to show through where erosion of its covering is taking place. Many people walk past this mound and have no idea what its former use would have been. Grid Reference SU 2002 1412

The remains of this are still very much in evidence as a large mound of earth that covers the concrete structure. It was massively built, and demolition was not considered an option after the war, therefore the target was simply covered over with earth. Concrete is starting to show through where erosion of its covering is taking place. Many people walk past this mound and have no idea what its former use would have been. Grid Reference SU 2002 1412

Tallboy Crater

This crater was created by a 12,000Ib bomb and today resembles a small open expanse of water. It is often now used by New Forest ponies as a watering hole. This is the most obvious crater of its type. Incidentally the one and only live test Grand Slam crater was filled in after the war. Grid Reference SU 1995 1407

This crater was created by a 12,000Ib bomb and today resembles a small open expanse of water. It is often now used by New Forest ponies as a watering hole. This is the most obvious crater of its type. Incidentally the one and only live test Grand Slam crater was filled in after the war. Grid Reference SU 1995 1407

Other Remains

Observation Hut

This is located near Amberwood and is one of the few remaining structures on the range. If you look carefully at the end wall of the hut you can see where an enterprising bricklayer has formed the letter V, presumably for Victory.

Grid Reference SU 2194 1640

Observation Hut

This is located near Amberwood and is one of the few remaining structures on the range. If you look carefully at the end wall of the hut you can see where an enterprising bricklayer has formed the letter V, presumably for Victory.

Grid Reference SU 2194 1640

Detail display panels at the remains of The Main Practice Tower located on Hampton Ridge. Grid Reference SU 1882 1360

Located next to the Main Practice Tower is this large white concrete direction arrow which points towards Ley Gutter where an illuminated target was positioned. Grid Reference SU 1883 1359

The remains of cast concrete light boxes at the Illuminated Target location below Ley Gutter.

Grid Reference SU 1913 1279

Grid Reference SU 1913 1279

Detail of an individual light box.

Pieces of shrapnel can still be found on the surface.

North Observation Tower Direction Arrow. Grid Reference SU 2031 1651

North Observation Tower Detail Display Panels.

So in conclusion, Ashley Walk has gone from one extreme to another and then back again. Today all is quiet and nature has reclaimed its land back from the days of noise, explosions and flying shrapnel, as can be seen in the photograph below, which is one of the access paths to the range.

It is hard now to consider what went on at the range, but if you know where to look and you don’t mind doing a bit of walking, you can still find the evidence.

Sources -

Ashley Walk - Its Bombing Range Landscape And History - Anthony Pasmore and Norman Parker

Lancaster At War 2 - Mike Garbett and Brian Goulding

Bomber Command 1936 - 1968 - Ken Delve

One Hell Of A Bomb - Stephen Flower

The Bomber Command Handbook 1939 - 1945 - Jonathan Falconer

Frank Pleszak

Tony Dowland

Neville Cullingford

Dr Robert Owen

Sources -

Ashley Walk - Its Bombing Range Landscape And History - Anthony Pasmore and Norman Parker

Lancaster At War 2 - Mike Garbett and Brian Goulding

Bomber Command 1936 - 1968 - Ken Delve

One Hell Of A Bomb - Stephen Flower

The Bomber Command Handbook 1939 - 1945 - Jonathan Falconer

Frank Pleszak

Tony Dowland

Neville Cullingford

Dr Robert Owen