RAF Bardney and Bomber Command

Over Europe

Written By Richard Hall

The airfield at Bardney was located ten miles east of Lincoln and four miles south of Wragby. As the bombing campaign over occupied Europe developed and became more intense, Bomber Command required more airfields to sustain its ever-strengthening power

|

Bardney was first surveyed in 1941, and with the land being flat and workable, it was decided to construct an airfield as a satellite to nearby RAF Waddington, under the control of 5 Group.

In 1942 construction commenced of a Class A airfield with opening delayed until April 1943 due to a shortage of materials. Three runways were laid 07-25 at 2,000 yards, 02-20 and 12-30 at 1,400 yards. Originally thirty-six hardstandings were connected to the perimeter track, with one lost due to the construction of a B.1 hangar at the head of runway 30. Two T.2 hangars were also erected with the bomb dump located to the northeast side between runway heads 07 and 12. Seven domestic, two WAAF, two communal sites, and sick quarters were dispersed to the south between New Park Wood and Birt Hill, with accommodation provided for 1,947 male and 401 female service personnel. |

In April 1943, 9 Squadron arrived at Bardney from RAF Waddington to begin the units association with the airfield that was to last until the end of hostilities. The squadron had long been at war by the time it took up residence at its new home. From the earliest days of the conflict, the unit had been in action and suffered some of the first losses of the war. Flying from RAF Honington on 4 September 1939, Vickers Wellington Is L4268 and L4275 were shot down while taking part in a raid on two German battleships anchored in Brunsbuttel with the loss of 10 crew members.

In August 1942, 9 Squadron transferred to 5 Group and moved to Waddington, where the unit converted on to the Avro Lancaster. Leaving Waddington on the evening of 13 April 1943, the Squadron took part in a raid on the port of La Spezia in Northern Italy. Returning to England on 14 April, the unit landed at Bardney to be greeted by their ground crews who had moved overnight from Waddington. In this instance, all the aircrew that left to take part in the operation returned safely.

In August 1942, 9 Squadron transferred to 5 Group and moved to Waddington, where the unit converted on to the Avro Lancaster. Leaving Waddington on the evening of 13 April 1943, the Squadron took part in a raid on the port of La Spezia in Northern Italy. Returning to England on 14 April, the unit landed at Bardney to be greeted by their ground crews who had moved overnight from Waddington. In this instance, all the aircrew that left to take part in the operation returned safely.

The Battle of the Ruhr

By March 1943, Bomber Command's Commander in Chief Sir Arthur Harris had built up his forces to the extent that he felt the time was now right to launch sustained major attacks on German industry in the Ruhr Valley. Although he did not solely concentrate on the Ruhr during this time, to have done so would have given the Luftwaffe's night fighters, flak defences and searchlights the chance to focus their efforts on defeating the attacking bombers.

Roughly two-thirds of the Command's efforts were targeted on the Ruhr, with the remainder scattered all over Europe, which helped disperse the defences. The Ruhr was also in range of Mosquitos that carried the blind bombing device known as Oboe. This electronic aid gave a better target marking accuracy and made the Command's raids more effective and efficient.

The Battle of the Ruhr commenced on 5/6 March 1943 with a raid on Essen. It continued until 31 July 1943 with an operation to Remscheid. 9 Squadron's arrival at Bardney coincided with Bomber Command's increasing attacks on Germany's industrial heartland. They were soon in action with an operation to Stuttgart on 14 April 1943. Five crews took part in the raid, which was a credit to the ground crews who had only arrived from Waddington overnight. Twenty-five aircraft either failed to return or were lost for operational reasons, but on this date, all 9 Squadron aircraft returned safely.

The first operational loss sustained by 9 Squadron flying from Bardney occurred on 30 April/1 May 1943. Lancaster III ED838 WS-R was tasked to take part in a raid on Essen. The aircraft piloted by Flg Off Nunez, who came from St Joseph Trinidad, was lost without a trace with the crew commemorated on the Runnymede Memorial.

By March 1943, Bomber Command's Commander in Chief Sir Arthur Harris had built up his forces to the extent that he felt the time was now right to launch sustained major attacks on German industry in the Ruhr Valley. Although he did not solely concentrate on the Ruhr during this time, to have done so would have given the Luftwaffe's night fighters, flak defences and searchlights the chance to focus their efforts on defeating the attacking bombers.

Roughly two-thirds of the Command's efforts were targeted on the Ruhr, with the remainder scattered all over Europe, which helped disperse the defences. The Ruhr was also in range of Mosquitos that carried the blind bombing device known as Oboe. This electronic aid gave a better target marking accuracy and made the Command's raids more effective and efficient.

The Battle of the Ruhr commenced on 5/6 March 1943 with a raid on Essen. It continued until 31 July 1943 with an operation to Remscheid. 9 Squadron's arrival at Bardney coincided with Bomber Command's increasing attacks on Germany's industrial heartland. They were soon in action with an operation to Stuttgart on 14 April 1943. Five crews took part in the raid, which was a credit to the ground crews who had only arrived from Waddington overnight. Twenty-five aircraft either failed to return or were lost for operational reasons, but on this date, all 9 Squadron aircraft returned safely.

The first operational loss sustained by 9 Squadron flying from Bardney occurred on 30 April/1 May 1943. Lancaster III ED838 WS-R was tasked to take part in a raid on Essen. The aircraft piloted by Flg Off Nunez, who came from St Joseph Trinidad, was lost without a trace with the crew commemorated on the Runnymede Memorial.

|

The photo on the left has been obtained from the Imperial War Museum. It shows a crew and Lancaster involved in the Battle of the Ruhr while flying with 9 Squadron from Bardney.

In the photo, Lancaster III ED831 WS-H crew are seen boarding their aircraft on 20 June 1943 for an operation to the Zeppelin Works at Friedrichshafen. The bomber is captained by Sqn Ldr A M Hobbs DFC RNZAF and was one of 60 Lancasters to participate in the raid. The Zeppelin works made Wurzburg radars an integral link in the Luftwaffe's control of night fighters, which were causing continuing losses to Bomber Command. |

The raid itself was one of the first to use what became known as the Master Bomber (MB) technique. This was where the attack was controlled by the pilot of one of the Lancasters, in this instance from 97 Squadron. The MB acted as Pathfinder and dropped target markers at which the first bombs were aimed. The attack then proceeded with a time and distance run commenced on the shores of Lake Constance to the estimated position of the works. Post raid reconnaissance showed that ten per cent of the bombs hit the factory with substantial damage caused.

|

The raid was also the first of what was known as a 'Shuttle Raid' where instead of returning to their home bases, the bombers flew onto and landed at Blida in North Africa. This way of operating caused confusion to the Luftwaffe's night fighters, who were waiting for the bombers to return over France. On this raid, no aircraft were lost, and all reached North Africa safely.

The photo on the right shows Lancaster III ED831 departing Bardney for the raid on Friedrichshafen. Raiding Spezia in Italy on the return journey from North Africa, ED831 arrived back at its home airfield on 24 June 1943. |

The Loss of a Lancaster

Over the night of 24/25 June 1943, Lancaster III ED831 took part in an operation to Elberfeld, this time piloted by Sgt G E Hall. Arriving back at Bardney at 04.20 hrs, the aircraft was rostered for a further sortie to Gelsenkirchen over the night of 25/26 June.

Taking off at 22.30 hrs, ED831 was again piloted by Sqn Ldr A M Hobbs, but this time with an eighth crew member. Fg Off John Hamilton Sams had been posted to Bardney from 1660 Heavy Conversion Unit on the same day as the operation to Gelsenkirchen. He was flying as 'Second Dickie' to gain experience on an operational sortie with the crew of ED831. Bardney's Operations Record Book shows ED831 as missing, no signals received. Thirty aircraft were lost on this raid to night fighters, including 13 Lancasters. ED831 was one of them, with none of the crew surviving.

Fg Off Sams, a graduate of Oxford University, would have gone through a rigorous selection process where only the best would succeed. He would have likely flown Tiger Moths in Britain, progressed to more advanced types such as the Boeing Stearman in the USA or maybe Cornells and Ansons in Canada, where he would have gained his wings. Then, finally, he would have returned to England to learn how to fly and convert to four-engine heavy bombers. Once this was completed successfully, he would have been posted to an operational squadron, in this case, 9 at Bardney.

To give him an idea of what to expect from operational flying, he would fly with an experienced crew over Germany on the night of 25/26 June 1943. Second Dickies were not always welcome as many bombers were lost while they were on board. Some considered them to be a jinx, with superstition high in the minds of a lot of bomber crew members. All the same, to go through the selection, training and the human emotions that would have gone with it, to be lost as a Second Dickie is a tragic waste of a young life.

Over the night of 24/25 June 1943, Lancaster III ED831 took part in an operation to Elberfeld, this time piloted by Sgt G E Hall. Arriving back at Bardney at 04.20 hrs, the aircraft was rostered for a further sortie to Gelsenkirchen over the night of 25/26 June.

Taking off at 22.30 hrs, ED831 was again piloted by Sqn Ldr A M Hobbs, but this time with an eighth crew member. Fg Off John Hamilton Sams had been posted to Bardney from 1660 Heavy Conversion Unit on the same day as the operation to Gelsenkirchen. He was flying as 'Second Dickie' to gain experience on an operational sortie with the crew of ED831. Bardney's Operations Record Book shows ED831 as missing, no signals received. Thirty aircraft were lost on this raid to night fighters, including 13 Lancasters. ED831 was one of them, with none of the crew surviving.

Fg Off Sams, a graduate of Oxford University, would have gone through a rigorous selection process where only the best would succeed. He would have likely flown Tiger Moths in Britain, progressed to more advanced types such as the Boeing Stearman in the USA or maybe Cornells and Ansons in Canada, where he would have gained his wings. Then, finally, he would have returned to England to learn how to fly and convert to four-engine heavy bombers. Once this was completed successfully, he would have been posted to an operational squadron, in this case, 9 at Bardney.

To give him an idea of what to expect from operational flying, he would fly with an experienced crew over Germany on the night of 25/26 June 1943. Second Dickies were not always welcome as many bombers were lost while they were on board. Some considered them to be a jinx, with superstition high in the minds of a lot of bomber crew members. All the same, to go through the selection, training and the human emotions that would have gone with it, to be lost as a Second Dickie is a tragic waste of a young life.

Operations Continue

|

The Battle of the Ruhr concluded on 24 July 1943. But there was no respite for the crews of Bomber Command or 9 Squadron as Harris launched Operation Gomorrah, the code name given to the bombing of Hamburg, Europe's largest port and Germany's second-largest city, which opened on 24/25 July 1943.

The attack on the city began using Pathfinder and Main Force squadrons, also for the first time, 'Window' was employed to jam Luftwaffe radars. It proved a success with 12 bombers failing to return out of a force of 791 that took part in the raid, a loss rate of 1.5%. |

Hamburg was not just to suffer by night but also by day as the USAAF 8th Air Force carried out raids, hampered by smoke caused by Bomber Command's efforts the night before. A return to Hamburg was made on 27/28 July. A warm summer night and dry conditions saw a phenomenon never before witnessed during the four years of war. A rain of high explosives and incendiaries caused a firestorm estimated to have killed between 35,000 to 45,000 people, with most of them being suffocated. Bomber crews reported seeing smoke rise to 20,000ft into the air, and it is said winds reached 120 mph at ground level.

Peenemunde

|

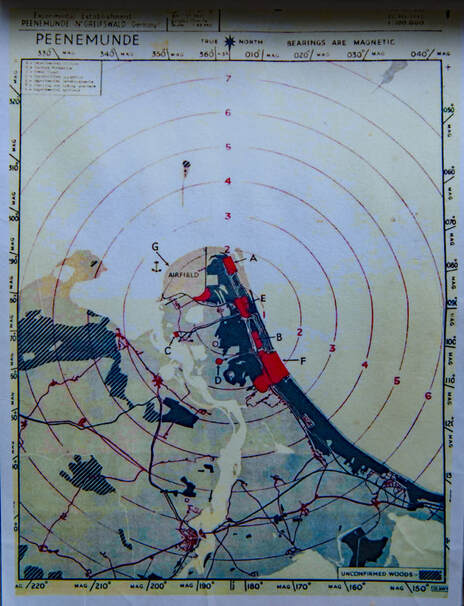

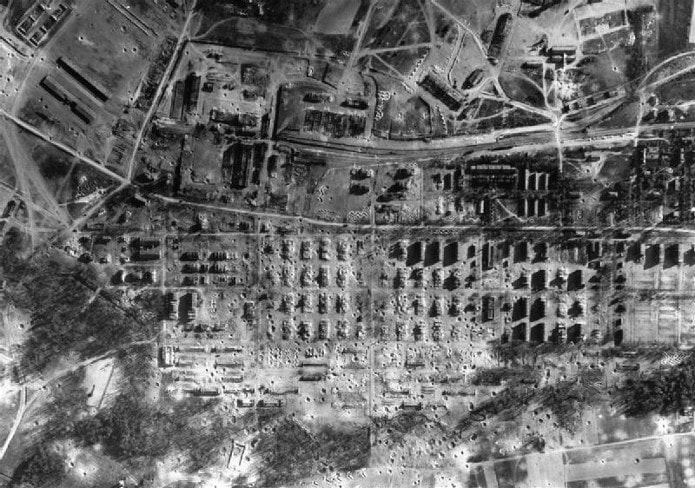

As early as May 1943, the Allies had become aware of the existence of construction sites in Northern France to launch V-1 flying bombs and V-2 rockets. The plans Hitler had to use these weapons became a priority for the Allies to defeat, and a number of operations were put into place.

Operation Hydra took place over the night of 17/18 August 1943 with Bomber Command attacking the Peenemunde Army Research Centre, with the aim of destroying the research facilities and killing the scientists. This attack was the opening of Operation Crossbow, the Allies strategic bombing campaign against the Nazi V weapon programme. The raid on Peenemunde resulted in a seven-week delay in V weapon production but came at a loss of 40 Bomber Command aircraft, 215 crew and many foreign workers in a nearby concentration camp. Crews from 9 Squadron took part in the raid with all aircraft returning safely. |

As the Summer turned to Autumn in 1943, the war for the Axis powers was not going well. Italy was near to surrendering, the Battle of the Atlantic was turning against the U-Boats, and the Russians had won a decisive victory at Kursk. At the tail end of August, Harris decided to again mount raids against Berlin, as the nights were drawing in and the cover of darkness was needed to attack this most well-defended of cities. On 23/24 August, a raid to Berlin was undertaken with all 9 Squadron Lancasters returning safely. The unit had been lucky as a total of 56 bombers were lost on this night, with the Halifax and Stirling squadrons being particularly hard hit. A loss rate of 7.9% made this the most costly raid for Bomber Command so far in the war, although the worst was yet to come.

Over the coming month's raids were mounted on Nuremberg, Monchengladbach, Berlin, Mannheim, Munich, Boulogne, Montlucon, Modane, Hannover, Bochum, Hagen, Kassel, Frankfurt, Stuttgart, Bremen, Leipzig, Dusseldorf, Cologne, Cannes and Ludwigshafen as well as minor operations to a variety of targets, a period of very intense operations for Bomber Command.

Over the coming month's raids were mounted on Nuremberg, Monchengladbach, Berlin, Mannheim, Munich, Boulogne, Montlucon, Modane, Hannover, Bochum, Hagen, Kassel, Frankfurt, Stuttgart, Bremen, Leipzig, Dusseldorf, Cologne, Cannes and Ludwigshafen as well as minor operations to a variety of targets, a period of very intense operations for Bomber Command.

The Battle of Berlin

|

The most important test of the war for Bomber Command commenced on 18/19 November 1943 when an attack on the German capital Berlin was undertaken. Harris had decided that Berlin should be reduced to a wasteland, and in his mind, its destruction would bring about the end of the war.

For the next four and a half months, Harris more or less had a free hand in pursuing his aim of bringing about Berlin's demise. Thirty-two missions were launched during the period, sixteen to Berlin and sixteen to other large cities. Crews not only had to contend with poor winter weather and long flight distances but also a reinvigorated Luftwaffe night fighter force, who had found ways of counteracting the advantages of Window and were taking an ever-increasing toll of the Command's aircraft. From a technical perspective, new models of the navigation aid H2S were being fitted to Pathfinder aircraft, which was fortunate as the use of Oboe was out of the question due to the distance of the targets rendering it ineffective. |

|

In the period from August to the third week in November, heavy losses forced Harris to withdraw the Stirling from the main force. This entailed Bomber Command losing 11 squadrons of aircraft, which could be ill afforded. Furthermore, Harris's aim of destroying the German capital was becoming somewhat more difficult. With the withdrawal of the Stirlings, losses among Halifax II and Vs began to rise, entailing a further number of squadrons being retired from the main force. Harris had lost approximately 250 aircraft and nigh on 20% of his bomb-carrying capacity due to the removal of the Stirling and the reduction of Halifax bombers from the theatre of war.

|

The withdrawal of the two aircraft types put additional strain on the remaining Lancaster squadrons, who stepped up to the mark to fill the void. The main offensive of the Battle of Berlin ran from 18/19 November to the end of January 1944, with the Command's effectiveness slowly deteriorating in the face of mounting losses and a decline in crew morale.

In February and March 1944, raids were made on lesser German cities, with two more taking place to Berlin before the month's end. Harris's vision of destroying the capital city had not come to fruition, with the Germans no nearer surrendering than they were at the beginning of the bombing operations. The Battle of Berlin ended on the night of 24/25 March 1944. There is no question that Bomber Command had just completed its toughest test yet to date with heavy losses in aircraft and crews. A game of cat and mouse had developed between the two sides with regards to each trying to get the technological advantage in night fighting techniques, countermeasures and tactics.

Nuremburg

Again there was to be no respite for the Bomber Command crews following the Battle of Berlin. Operations took place on 25/26 and 26/27 March to Aulnoye and Essen, respectively. On 30/31 March, Nuremberg was the target, and this raid would go down in the history of Bomber Command for all the wrong reasons. Another stamp in the record book would be made, which would make bleak reading for future historians.

The Main Force was sent on the 8 hour round trip to Nuremberg, despite reports that weather conditions were not favourable for the raid. In total, 795 bombers were dispatched, and, in bright moonlight, the Luftwaffe's night fighters were met, which accounted for 82 of the Command's aircraft on the flight to the target. Conditions on the night also led to contrails forming, making it easier for the night fighters to see and intercept their quarry. In total, 94 aircraft were lost on the raid, Bomber Command's most significant loss on one operation of the war.

A further 10 aircraft crashed in England, and 1 was written off due to severe battle damage. The bombing of Nuremberg was ineffective, and at least 120 bombers dropped their loads on Schweinfurt, the cause of this being poor navigation brought on by poorly forecast winds. 9 Squadron dispatched 16 Lancasters to Nuremberg, resulting in 1 lost, W5006 WS-X, to a Bf 110 night fighter. Although in light of the night's events, 9 Squadron had fared well, the crews, upon learning of the scale of the losses, must have breathed a sigh of relief at Bardney as they settled in for a well-earned sleep at the end of their debriefs. When looking at Bardney's losses, it should be considered that this was emulated across many Bomber Command airfields in Britain. Multiply the losses up, and it is not hard to see how the final count of bomber crews who did not live to fight another day reached 55,573 by the war's end.

D-Day Preparations

The first three months of 1944 had been a torrid time for Bomber Command with heavy losses among aircraft and crews, the sad outcome of this was there was little to show in the way of results for the effort expended. With D-Day in the planning stage, on 14 April, Bomber Command came under the control of Supreme Headquarters Allied Expeditionary Force (SHAEF). Bombing operations were changing from strategic to tactical. Raids were switched to targets in Occupied Europe and the transportation system in Western Germany. Harris was not all pleased that the efforts of Bomber Command were being used in such a way, but he gave his full support to the Directive he had been given. He was, however, allowed a bit of leeway as the Directive also stated, "Bomber Command will continue to be employed in accordance with their main aim of disorganizing German industry".

From 1 April to 6 June 1944 Bomber Command undertook raids to targets throughout Occupied Europe, Germany, and mine laying and operations in support of the Special Operations Executive (SOE).

In February and March 1944, raids were made on lesser German cities, with two more taking place to Berlin before the month's end. Harris's vision of destroying the capital city had not come to fruition, with the Germans no nearer surrendering than they were at the beginning of the bombing operations. The Battle of Berlin ended on the night of 24/25 March 1944. There is no question that Bomber Command had just completed its toughest test yet to date with heavy losses in aircraft and crews. A game of cat and mouse had developed between the two sides with regards to each trying to get the technological advantage in night fighting techniques, countermeasures and tactics.

Nuremburg

Again there was to be no respite for the Bomber Command crews following the Battle of Berlin. Operations took place on 25/26 and 26/27 March to Aulnoye and Essen, respectively. On 30/31 March, Nuremberg was the target, and this raid would go down in the history of Bomber Command for all the wrong reasons. Another stamp in the record book would be made, which would make bleak reading for future historians.

The Main Force was sent on the 8 hour round trip to Nuremberg, despite reports that weather conditions were not favourable for the raid. In total, 795 bombers were dispatched, and, in bright moonlight, the Luftwaffe's night fighters were met, which accounted for 82 of the Command's aircraft on the flight to the target. Conditions on the night also led to contrails forming, making it easier for the night fighters to see and intercept their quarry. In total, 94 aircraft were lost on the raid, Bomber Command's most significant loss on one operation of the war.

A further 10 aircraft crashed in England, and 1 was written off due to severe battle damage. The bombing of Nuremberg was ineffective, and at least 120 bombers dropped their loads on Schweinfurt, the cause of this being poor navigation brought on by poorly forecast winds. 9 Squadron dispatched 16 Lancasters to Nuremberg, resulting in 1 lost, W5006 WS-X, to a Bf 110 night fighter. Although in light of the night's events, 9 Squadron had fared well, the crews, upon learning of the scale of the losses, must have breathed a sigh of relief at Bardney as they settled in for a well-earned sleep at the end of their debriefs. When looking at Bardney's losses, it should be considered that this was emulated across many Bomber Command airfields in Britain. Multiply the losses up, and it is not hard to see how the final count of bomber crews who did not live to fight another day reached 55,573 by the war's end.

D-Day Preparations

The first three months of 1944 had been a torrid time for Bomber Command with heavy losses among aircraft and crews, the sad outcome of this was there was little to show in the way of results for the effort expended. With D-Day in the planning stage, on 14 April, Bomber Command came under the control of Supreme Headquarters Allied Expeditionary Force (SHAEF). Bombing operations were changing from strategic to tactical. Raids were switched to targets in Occupied Europe and the transportation system in Western Germany. Harris was not all pleased that the efforts of Bomber Command were being used in such a way, but he gave his full support to the Directive he had been given. He was, however, allowed a bit of leeway as the Directive also stated, "Bomber Command will continue to be employed in accordance with their main aim of disorganizing German industry".

From 1 April to 6 June 1944 Bomber Command undertook raids to targets throughout Occupied Europe, Germany, and mine laying and operations in support of the Special Operations Executive (SOE).

|

One raid on 3/4 May led to 42 Lancasters being lost, including 1 that had flown from Bardney. The operation was to Mailly-Le-Camp in France, where a German military camp was situated. A combination of delays caused by issues with radio communications resulted in bombers circling, waiting for the order to attack. The delay allowed Luftwaffe night fighters to arrive and to wreak havoc amongst the bombers. The attack resulted in 1,500 tons of bombs falling on the camp, which destroyed barrack buildings, transport sheds, ammunition stores, vehicles and tanks.

|

After D-Day

D-Day went ahead on 6 June 1944 and allowed the Allies to obtain a foothold in Europe, which was in due course to enable its liberation. Bomber Command continued supporting operations, prioritised as attacks on V-weapon sites, road and rail communications, fuel depots, troop and armour concentrations/battlefield targets. The first week after the invasion saw Bomber Command fly 2,700 sorties at night to support the landings.

On 14 June, the first daylight raid for over a year took place when elements of 1, 3, 5 and 8 Groups attacked German naval assets threatening Allied shipping off the Normandy beaches. The raid including participation from 617 Squadron, who utilised 12,000-lb Tallboy bombs to attack concrete E-boat pens at Le Harve. Fighter cover from Spitfires of 11 Group helped ensure only one Lancaster from 15 Squadron was lost during the raid.

D-Day went ahead on 6 June 1944 and allowed the Allies to obtain a foothold in Europe, which was in due course to enable its liberation. Bomber Command continued supporting operations, prioritised as attacks on V-weapon sites, road and rail communications, fuel depots, troop and armour concentrations/battlefield targets. The first week after the invasion saw Bomber Command fly 2,700 sorties at night to support the landings.

On 14 June, the first daylight raid for over a year took place when elements of 1, 3, 5 and 8 Groups attacked German naval assets threatening Allied shipping off the Normandy beaches. The raid including participation from 617 Squadron, who utilised 12,000-lb Tallboy bombs to attack concrete E-boat pens at Le Harve. Fighter cover from Spitfires of 11 Group helped ensure only one Lancaster from 15 Squadron was lost during the raid.

|

The British 2nd Army's breakout from the Normandy beachhead was code-named Operation Goodwood, which commenced in July.

Two major raids were undertaken on 7 and 18 July to support Goodwood by Bomber Command to attack fortified villages in the Caen area. The raids resulted in the Germans being driven out, but considerable damage was caused to the local infrastructure. A force of nearly 700 bombers was tasked to the Normandy area to support American ground operations. |

Advances were quickly made through Northern France by Allied forces, stopping the Germans from mounting an effective counter-attack. Some raids were made into Germany but not to the extent that had been previously seen.

During August, further raids were undertaken in support of ground operations in the Normandy Battle Area. On the 7/8, 1,019 Lancasters, Halifaxes and Mosquitos attacked aiming points in front of Allied positions. A similar raid took place on 14 August, but on this occasion, bombs landed among Canadian troops killing 13 and injuring 53. This shows the difficulty of precision bombing with the tools then available to Bomber Command, who was more of a strategic rather than a tactical force.

Turning Point

The Allies made quick progress after they broke through the German defences in Normandy, Paris was liberated on 24 August, and Belgium entered in September, yielding the vital port of Antwerp shortly after. On 14 September, Harris was released from his control by SHAEF. His Command reverted back to the Air Ministry, with the caveat it was to remain ready to answer any calls for assistance from ground forces as they moved towards Germany.

During August, further raids were undertaken in support of ground operations in the Normandy Battle Area. On the 7/8, 1,019 Lancasters, Halifaxes and Mosquitos attacked aiming points in front of Allied positions. A similar raid took place on 14 August, but on this occasion, bombs landed among Canadian troops killing 13 and injuring 53. This shows the difficulty of precision bombing with the tools then available to Bomber Command, who was more of a strategic rather than a tactical force.

Turning Point

The Allies made quick progress after they broke through the German defences in Normandy, Paris was liberated on 24 August, and Belgium entered in September, yielding the vital port of Antwerp shortly after. On 14 September, Harris was released from his control by SHAEF. His Command reverted back to the Air Ministry, with the caveat it was to remain ready to answer any calls for assistance from ground forces as they moved towards Germany.

|

On the 16/17 September Bomber Command's operations were in support of British and American airborne forces at Arnhem and Nijmegen, which was part of an operation known as Market Garden. The Operation ultimately failed due to the Allies overextending themselves and with stiffer resistance than anticipated being met, any chance of the war being over by Christmas had now evaporated.

Harris had no problem with providing this kind of support and remained ready to respond as required, but this only committed a small part of his now considerable force, so what was the best way now to employ Bomber Command and make the best use of this valuable resource? |

Three schools of thought were prevailing at the time, which was attacks on synthetic oil production, the German transportation system and a less favoured option of a return to the strategic bombing of German industrial cities. However, a directive issued on 25 September to both Bomber Command and the American 8th Air Force made it clear that the oil option had won with a secondary objective to attack the German rail, waterway transport system and also tank and vehicle production. Later in the Directive, it stated that when weather or tactical conditions precluded operations on the primary targets, German cities were cited for general attack. This gave Harris all he needed to continue with his raids on the cities as he did not feel attacks on the oil industry were the best use of the force at his disposal. However, many of the areas targeted were associated with oil production.

During this time, Bomber Command's strength continued to grow, bombing aids improved, and electronic measures were further implemented to outwit the Germans. Even cloud cover now failed to protect their cities. The Luftwaffe night fighter force was in decline, and bomber casualties were reducing. The scene was set that was to lead to the ultimate victory.

Bomber Command ranged far and wide to targets that included Brunswick, Nuremberg, the Ruhr, Darmstadt, Bremerhaven, Bonn, Freiburg, Heilbronn and Ulm. Crews flew by day and night, their logbooks showing attacks on a variety of targets which encompassed gun batteries in France, the Dortmund Ems Canal, obscure German rail yards and even the Tirpitz, which was ultimately sunk in a Norwegian Fjord. The extent of the raids can be seen in that 46% of the total tonnage of bombs dropped by the Command would be in the last nine months of the war.

Since opening, Bardney had been home to one squadron, but this changed on 7 October 1944 when 227 Squadron partially reformed at the airfield from 9 Squadron's A Flight before moving out to RAF Balderton a couple of weeks later. On 15 October 1944, 189 Squadron formed at Bardney, staying until 2 November before moving to RAF Fulbeck.

During this time, Bomber Command's strength continued to grow, bombing aids improved, and electronic measures were further implemented to outwit the Germans. Even cloud cover now failed to protect their cities. The Luftwaffe night fighter force was in decline, and bomber casualties were reducing. The scene was set that was to lead to the ultimate victory.

Bomber Command ranged far and wide to targets that included Brunswick, Nuremberg, the Ruhr, Darmstadt, Bremerhaven, Bonn, Freiburg, Heilbronn and Ulm. Crews flew by day and night, their logbooks showing attacks on a variety of targets which encompassed gun batteries in France, the Dortmund Ems Canal, obscure German rail yards and even the Tirpitz, which was ultimately sunk in a Norwegian Fjord. The extent of the raids can be seen in that 46% of the total tonnage of bombs dropped by the Command would be in the last nine months of the war.

Since opening, Bardney had been home to one squadron, but this changed on 7 October 1944 when 227 Squadron partially reformed at the airfield from 9 Squadron's A Flight before moving out to RAF Balderton a couple of weeks later. On 15 October 1944, 189 Squadron formed at Bardney, staying until 2 November before moving to RAF Fulbeck.

Tallboy Operations

|

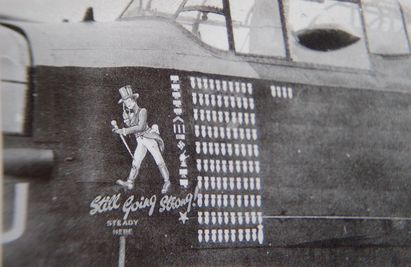

Avro Lancaster I W4964 left the A V Roe factory on 12 April 1943 and, in due course, was assigned to 9 Squadron. The average survival expectancy of a Lancaster in service was three weeks, but some lasted a lot longer. W4964 was one such aircraft. Following arrival at Bardney, W4964 was given the squadron code WS-J (J-Johnny), which lead to nose art being applied between the pilot's port side window and the front gun turret, depicting the Johnny Walker whiskey symbol and the motto 'Still Going Strong'.

|

W4964 commenced operations on 20/21 April 1943 and slowly began notching up missions. By the time of its 100th, 9 Squadron had been given the important task of attacking the 45,000-ton battleship Tirpitz in Kafjord Norway, an attack where its Lancasters would carry 12,000Ib Tallboy bombs, designed by Barnes Wallis

|

The Tirpitz had long been a thorn in the side of the British. Even with the ship holed up in Norway and not at sea, it was still seen as a threat that required elimination. There was concern that the vessel was about to leave Kafjord and therefore pose a risk to the Royal Navy's Arctic convoys supplying the Russians. Operations were planned that would see 9 and 617 Squadrons attack the Tirpitz with Tallboys under the code name Paravane. The Lancaster did not have the range to reach the ship when carrying a Tallboy from Britain, dictating that the two squadrons deploying to operate from an airfield closer to the beast's lair.

|

The Russians provided an airfield at Yagodnik near Archangel, some 600 miles from the Tirpitz, which entailed the planned raids were feasible. Accordingly, on 11 September 1944, 18 Lancasters from 9 Squadron led by Wg Cdr James Bazin and 20 from 617 Squadron commanded by Wg Cdr Willie Tait flying from RAF Woodhall Spa, flew to RAF Lossiemouth in Scotland before departing to Yagodnik. One Lancaster turned back over the North Sea with the remainder pressing on to be met with fog over their destination airfield. Six aircraft crashed in Russia, with all crews surviving. Of the 38 Lancasters that departed Lossiemouth, 27 and a camera ship were available to take part in the raid planned for 15 September. Twenty aircraft were loaded with Tallboys, with the remainder carrying 500Ib Johnny Walker mines, a weapon designed to attack capital ships in shallow water.

|

As the Lancasters ran into the attack, a small amount of cloud drifted across the Fjord, which, together with the ship's smokescreen, prevented the crews from observing the results of their bombing. One Tallboy had hit the battleship near the bow causing considerable damage. The ship's engines were also damaged either from the hit or near misses. The Germans decided it was impractical to make the Tirpitz fully seaworthy, so they moved her to an anchorage near Tromso. Here she would act as a semi-static heavy artillery battery to protect northern flanks against a feared Allied invasion. The British were unaware that the Tirpitz was no longer a threat to other shipping and planned further operations to put the ship out of commission. No Lancasters were lost during the first operation, although one from 617 Squadron crashed in Norway while returning to Lossiemouth two days later.

Moving the Tirpitz put her within range of Lancasters flying from Scotland. Operation Obviate took place on 29 October 1944 with 18 Lancasters each from 9 and 617 Squadrons together with an aircraft from a film unit. The Lancasters taking part in the raid had their mid-upper turret and other equipment removed to enable additional fuel to be carried to complete the 2,250-mile round trip.

|

An earlier weather sortie by a Mosquito showed the target area to be clear of cloud. Unfortunately, when the Lancasters arrived to commence their attack, the Tirpitz was covered. Thirty-two Lancasters released their Tallboys on the estimated position of the ship, but no hits were recorded. One 617 Squadron Lancaster was hit by flak and crash-landed in Sweden, its crew later returning to Britain.

A third raid was planned to the Tirpitz named Operation Catechism, and this took place on 12 November 1944. Thirty Lancasters from 9 and 617 Squadrons with a camera ship from 463 Squadron (RAAF) took off from Lossiemouth and flew to Tromso, where they found the battleship in clear conditions. Tirpitz was hit by at least two Tallboys which caused a violent internal explosion. The ship capsized and was a total loss, approximately 1,000 of her 1,900 crew were killed. Nearby Luftwaffe fighters stationed to protect the vessel did not take off in time, resulting in one 9 Lancaster being hit by flak and landing in Sweden, its crew unhurt.

9 Squadron had become known as a specialist bombing unit within Bomber Command and were tasked on further occasions to use Tallboys as and when the need arose.

Re-organisation and the Battle of the Bulge

Bomber Command's rapid expansion during the war put a strain on organisational administration, resulting in an intermediate level of command being put in place between Group HQs and individual stations. This was known as the Base System, which consisted of a Base station with either one or two substations. An Air Commodore commanded the Base station, with each Base being identified by a two-digit number. The first identified the Group, the second the number of that Base within the Group. Thus, on 14 November 1944, RAF Bardney (9 Squadron) and RAF Skellingthorpe (50 and 61 Squadrons) joined RAF Waddington (463 and 467 Squadrons) in becoming 53 Base - Waddington.

A third raid was planned to the Tirpitz named Operation Catechism, and this took place on 12 November 1944. Thirty Lancasters from 9 and 617 Squadrons with a camera ship from 463 Squadron (RAAF) took off from Lossiemouth and flew to Tromso, where they found the battleship in clear conditions. Tirpitz was hit by at least two Tallboys which caused a violent internal explosion. The ship capsized and was a total loss, approximately 1,000 of her 1,900 crew were killed. Nearby Luftwaffe fighters stationed to protect the vessel did not take off in time, resulting in one 9 Lancaster being hit by flak and landing in Sweden, its crew unhurt.

9 Squadron had become known as a specialist bombing unit within Bomber Command and were tasked on further occasions to use Tallboys as and when the need arose.

Re-organisation and the Battle of the Bulge

Bomber Command's rapid expansion during the war put a strain on organisational administration, resulting in an intermediate level of command being put in place between Group HQs and individual stations. This was known as the Base System, which consisted of a Base station with either one or two substations. An Air Commodore commanded the Base station, with each Base being identified by a two-digit number. The first identified the Group, the second the number of that Base within the Group. Thus, on 14 November 1944, RAF Bardney (9 Squadron) and RAF Skellingthorpe (50 and 61 Squadrons) joined RAF Waddington (463 and 467 Squadrons) in becoming 53 Base - Waddington.

|

The war was drawing near to ending, but Hitler still had some surprises up his sleeve. In December 1944, the Germans launched their last offensive in the west with an attack through the Ardennes, which caught the Allies completely off guard.

The plan was to drive an attack through to the port of Antwerp, thus cutting off the Allied supply route. Bad weather hampered Allied air operations, and in what was to become known as the Battle of the Bulge, initial advances were made, but the Allies prevailed and pushed the offensive back. |

As the end of the year approached, most of Germany's major cities lay in ruins, the Ruhr continued to be attacked, the Allies and the Russians were advancing. However, Hitler and his henchmen showed no signs of surrendering, despite the suffering of the German people.

Towards Victory

Official History HMSO 1961 - In the last year of the war Bomber Command played a major part in the complete destruction of whole vital segments of German oil production, in the virtual dislocation of her communications system and in the elimination of other important activities.

The last major attack by the Luftwaffe took place on 1 January 1945 and supported the Battle of the Bulge. Operation Bodenplatt was planned to catch the Allied air forces off guard and so gain air superiority to allow the stalled advance of the German Army and Waffen SS on the battlefield to continue. The attack was a surprise, and many Allied aircraft were lost on the ground. However, the operation was ultimately a failure, with the Luftwaffe losing many machines and, more crucially, pilots, which could not be replaced at this stage of the war.

Towards Victory

Official History HMSO 1961 - In the last year of the war Bomber Command played a major part in the complete destruction of whole vital segments of German oil production, in the virtual dislocation of her communications system and in the elimination of other important activities.

The last major attack by the Luftwaffe took place on 1 January 1945 and supported the Battle of the Bulge. Operation Bodenplatt was planned to catch the Allied air forces off guard and so gain air superiority to allow the stalled advance of the German Army and Waffen SS on the battlefield to continue. The attack was a surprise, and many Allied aircraft were lost on the ground. However, the operation was ultimately a failure, with the Luftwaffe losing many machines and, more crucially, pilots, which could not be replaced at this stage of the war.

|

On the same day as Operation Bodenplatt, Lancaster PD377 of 9 Squadron took off from Bardney on an operation to the Dortmund-Ems Canal. Approaching the target and just at the point of bomb release, a heavy anti-aircraft shell hit the Lancaster just forward of the mid-upper gun turret. The resulting explosion took out the aircraft's control lines, inter-communications circuit and hydraulic pipes. A second shell hit the bomber's nose section causing the pilot Fg Off Harry Denton to lose consciousness momentarily. A fire that had broken out was fanned by the air rushing through the hole in the nose. Denton regained consciousness and control of the Lancaster, the navigator, Ted Kneebone, and bomb aimer Ron Goebel survived the explosions and fire, and a course was set for home. Mid-upper gunner Sgt Ernie Watts was unconscious in his turret, a fact noted by wireless operator Flt Sgt George Thompson. Without concern for his own welfare, Thompson braved fire and exploding ammunition and proceeded to rescue Watts, bringing him to safety and extinguishing the gunner's burning clothing with his bare hands.

|

Thompson received severe burns to his hands, legs and face, but he noticed rear gunner Sgt Haydn Price was also trapped in his turret. Once again, and despite his severe injuries, Thompson went to the rescue of Price and brought him to safety. The gunner's clothing was on fire, and Thompson again used his bare hands to extinguish the flames. Exhausted and in great pain, Thompson reported to Denton to appraise him of the situation, so burned was he Denton didn't recognise him.

Denton, with the help of Goebel and flight engineer, Wilf Hartshorn flew the Lancaster back to friendly lines and crash-landed near a Dutch village. On 23 January 1945, Thompson succumbed to his injuries, as did Ernie Potts, who Thompson had fought so gallantly to save, Haydn Price survived. In recognition of this selfless act of bravery, an announcement came on 20 February 1945 that Thompson would be awarded the Victoria Cross.

Harris now had a strength of over 1,400 aircraft, which at its peak would reach 1,625 bombers, most of them Lancasters. Losses continued to fall due to the overwhelming air superiority held by Allied airpower. Over the coming months, Bomber Command, in conjunction with the American 8th Air Force, systematically reduced Germany's capacity to fight by pounding them by day and night.

Precision attacks on bridges and viaducts by 9 and 617 Squadrons utilised Bomber Command's latest weapon known as the Grand Slam, also designed by Barnes Wallis. This massive munition weighed in at 22,000-lb and required specially modified Lancasters, flown by 617 Squadron, to carry it. Main Force raids continued against rail centres, marshalling yards, canals and aqueducts, while Fighter Command and fighters of the American 8th Air Force shot up anything that moved on the ground or didn't move for that matter.

In February, Bomber Command was ordered to take part in Operation Thunderclap. A series of raids on major communication centres immediately behind the Eastern Front were planned, packed with refugees fleeing from the Russians and with wounded troops. It was envisaged such attacks would produce transport and communication problems on a massive scale and aid the advance of the Russians westward to hasten the war's end. Stalin put pressure on Churchill to assist the Russian forces, and the British Prime Minister was keen to use Allied heavy bombers to achieve this end. Opposition from his own ministers failed to deter Churchill, who ordered plans to be drawn up to attack Berlin, Chemnitz, Dresden and Leipzig.

On 3 February, the USAAF bombed Berlin, and on 13/14 February, Bomber Command raided Dresden in what was to become one of the most controversial attacks of the war, which still causes argument to this day. Dresden was attacked in two waves, the second of which caused a firestorm that consumed an estimated 25,000 people. It is considered that this raid unfairly turned opinion against Bomber Command, Harris and his crews. No medal was struck for the Command at the war's end, which caused resentment from the crews for many years until this was addressed, partially, by the awarding in 2013 of a Bomber Command clasp.

Veterans saw the clasp as an insult for their sacrifices, and many never claimed the award. Harris was following the orders he'd been given, but when the chips were down, and he needed the support of Churchill, this was denied and can be seen as a betrayal and the scapegoating of Bomber Command's Commander In Chief and his brave crews; a very sorry episode indeed. Further raids were carried in February leading into March, and it was on 16/17 during a raid to Nuremberg, the Luftwaffe night fighters still showed they could exact a heavy toll. During this raid, 24 Lancasters were brought down. Fortunately for 9 Squadron, they attacked Wurzburg on this night without loss. Even at this late stage of the war, misery and loss came to haunt Lincolnshire's airfields at a time when most crews considered they might just survive.

Operation Gisela

At this point of the war, there was not much of a threat expected from the Luftwaffe, especially over England. However, this idea was dispelled on 3/4 March 1945 when intruders (Luftwaffe night fighters) were in action over England as part of Operation Gisela.

Denton, with the help of Goebel and flight engineer, Wilf Hartshorn flew the Lancaster back to friendly lines and crash-landed near a Dutch village. On 23 January 1945, Thompson succumbed to his injuries, as did Ernie Potts, who Thompson had fought so gallantly to save, Haydn Price survived. In recognition of this selfless act of bravery, an announcement came on 20 February 1945 that Thompson would be awarded the Victoria Cross.

Harris now had a strength of over 1,400 aircraft, which at its peak would reach 1,625 bombers, most of them Lancasters. Losses continued to fall due to the overwhelming air superiority held by Allied airpower. Over the coming months, Bomber Command, in conjunction with the American 8th Air Force, systematically reduced Germany's capacity to fight by pounding them by day and night.

Precision attacks on bridges and viaducts by 9 and 617 Squadrons utilised Bomber Command's latest weapon known as the Grand Slam, also designed by Barnes Wallis. This massive munition weighed in at 22,000-lb and required specially modified Lancasters, flown by 617 Squadron, to carry it. Main Force raids continued against rail centres, marshalling yards, canals and aqueducts, while Fighter Command and fighters of the American 8th Air Force shot up anything that moved on the ground or didn't move for that matter.

In February, Bomber Command was ordered to take part in Operation Thunderclap. A series of raids on major communication centres immediately behind the Eastern Front were planned, packed with refugees fleeing from the Russians and with wounded troops. It was envisaged such attacks would produce transport and communication problems on a massive scale and aid the advance of the Russians westward to hasten the war's end. Stalin put pressure on Churchill to assist the Russian forces, and the British Prime Minister was keen to use Allied heavy bombers to achieve this end. Opposition from his own ministers failed to deter Churchill, who ordered plans to be drawn up to attack Berlin, Chemnitz, Dresden and Leipzig.

On 3 February, the USAAF bombed Berlin, and on 13/14 February, Bomber Command raided Dresden in what was to become one of the most controversial attacks of the war, which still causes argument to this day. Dresden was attacked in two waves, the second of which caused a firestorm that consumed an estimated 25,000 people. It is considered that this raid unfairly turned opinion against Bomber Command, Harris and his crews. No medal was struck for the Command at the war's end, which caused resentment from the crews for many years until this was addressed, partially, by the awarding in 2013 of a Bomber Command clasp.

Veterans saw the clasp as an insult for their sacrifices, and many never claimed the award. Harris was following the orders he'd been given, but when the chips were down, and he needed the support of Churchill, this was denied and can be seen as a betrayal and the scapegoating of Bomber Command's Commander In Chief and his brave crews; a very sorry episode indeed. Further raids were carried in February leading into March, and it was on 16/17 during a raid to Nuremberg, the Luftwaffe night fighters still showed they could exact a heavy toll. During this raid, 24 Lancasters were brought down. Fortunately for 9 Squadron, they attacked Wurzburg on this night without loss. Even at this late stage of the war, misery and loss came to haunt Lincolnshire's airfields at a time when most crews considered they might just survive.

Operation Gisela

At this point of the war, there was not much of a threat expected from the Luftwaffe, especially over England. However, this idea was dispelled on 3/4 March 1945 when intruders (Luftwaffe night fighters) were in action over England as part of Operation Gisela.

|

Over 140 Luftwaffe crews were briefed to carry out a mass intruder mission over England, with the aim of the operation being to attack RAF bombers as they were returning to their home airfields, a time when crews were likely to be relaxing and therefore off their guard following a long and arduous trip.

In total, 23 bombers and 1 Mosquito were brought down by the intruders, with a further 20 aircraft damaged. However, the Luftwaffe didn't have it all their own way, with 8 night fighters failing to return. |

This type of action by the Luftwaffe was highly effective and, had it been more consistent, could have had a significant effect on the RAF's operations. Luckily Hitler intervened and decreed that intruder operations over Britain should be limited as he wanted the German populace to see RAF bombers being shot down over the homeland. He considered this would help bolster morale. But, once again, Hitler's flawed thought processes ignored best military practice for the sake of his own views. Fortunately for 9 Squadron, no losses were suffered on the night of Operation Gisela.

The End in Sight

Raids in March continued to a variety of targets, including shipyards, U-boat pens, railway yards, bridges, and the few remaining oil plants. The last loss for 9 Squadron occurred on 8/9 April 1945. A raid was undertaken to an oil refinery in Lutzkendorf, during which Lancaster I NG235 WS-H was lost with all crew. Leaving RAF Fulbeck at 09.30 on 8 April 1945, 189 Squadron flew to Bardney to join 9 for the last few weeks of the war. 189 undertook their first operation from Bardney on 17/18 April 1945 to attack the railway yard at Pilsen with no losses.

Nuisance raids by Mosquito aircraft continued on Berlin, with the last major operation by 512 heavies taking place on Potsdam on 14/15 April. Much of Germany had been overrun by this time, but ports still needed to be captured. To facilitate this, Bomber Command attacked the Island of Heligoland on 18 April, which guarded the approach to Hamburg and the coastal batteries at Wangerooge, which defended the ports of Bremen and Wilhelmshaven.

9 Squadron flew their final mission on 25 April 1945 to Berchtesgaden, Hitler's Eagle's Nest and the local SS Guards barracks. Finally, 189 undertook their last operation of the war on 25/26 April and bombed the oil refinery at Tonsberg, with all aircraft returning safely. This was to be the last operation by Bomber Command heavy bombers in World War Two. Following this, Bomber Command went onto the more peaceful tasks of repatriation of prisoners of war and the dropping of food supplies (Operation Manna) to starving Dutch civilians.

The end of April 1945 saw some very significant events occurring. On the 12th, President Roosevelt died to be succeeded by Harry Truman. The 28th saw Benito Mussolini killed by Italian partisans, and two days later, Hitler, with his long term partner and now wife Eva Braun, committed suicide in his bunker in Berlin. Grand Admiral Karl Donitz succeeded him.

The very last operation flown by Bomber Command was on 2/3 May when Mosquitos of 8 Group and Halifax of 100 Group raided shipping at Kiel. Even at this late stage, losses continued, with one Mosquito and two Halifax failing to return. After just under six years, the war was finally over for Bomber Command.

The End in Sight

Raids in March continued to a variety of targets, including shipyards, U-boat pens, railway yards, bridges, and the few remaining oil plants. The last loss for 9 Squadron occurred on 8/9 April 1945. A raid was undertaken to an oil refinery in Lutzkendorf, during which Lancaster I NG235 WS-H was lost with all crew. Leaving RAF Fulbeck at 09.30 on 8 April 1945, 189 Squadron flew to Bardney to join 9 for the last few weeks of the war. 189 undertook their first operation from Bardney on 17/18 April 1945 to attack the railway yard at Pilsen with no losses.

Nuisance raids by Mosquito aircraft continued on Berlin, with the last major operation by 512 heavies taking place on Potsdam on 14/15 April. Much of Germany had been overrun by this time, but ports still needed to be captured. To facilitate this, Bomber Command attacked the Island of Heligoland on 18 April, which guarded the approach to Hamburg and the coastal batteries at Wangerooge, which defended the ports of Bremen and Wilhelmshaven.

9 Squadron flew their final mission on 25 April 1945 to Berchtesgaden, Hitler's Eagle's Nest and the local SS Guards barracks. Finally, 189 undertook their last operation of the war on 25/26 April and bombed the oil refinery at Tonsberg, with all aircraft returning safely. This was to be the last operation by Bomber Command heavy bombers in World War Two. Following this, Bomber Command went onto the more peaceful tasks of repatriation of prisoners of war and the dropping of food supplies (Operation Manna) to starving Dutch civilians.

The end of April 1945 saw some very significant events occurring. On the 12th, President Roosevelt died to be succeeded by Harry Truman. The 28th saw Benito Mussolini killed by Italian partisans, and two days later, Hitler, with his long term partner and now wife Eva Braun, committed suicide in his bunker in Berlin. Grand Admiral Karl Donitz succeeded him.

The very last operation flown by Bomber Command was on 2/3 May when Mosquitos of 8 Group and Halifax of 100 Group raided shipping at Kiel. Even at this late stage, losses continued, with one Mosquito and two Halifax failing to return. After just under six years, the war was finally over for Bomber Command.

|

On 8 May 1945, the war in Europe ended with the signing of a document entitled the German Instrument of Surrender. Its terms dictated the total unconditional surrender of Germany, and the day itself became known as Victory in Europe Day (VE Day).

RAF Bardney was just one airfield of the many that took part in Bomber Command's campaign over Europe. Nonetheless, it would have experienced the whole range of human emotions; fear, sorrow, anger, despair, hope, joy and sadness that goes with groups of people who did not know if they or their loved ones would live to see another day. |

Yet despite this, all those stationed at Bardney got on with their jobs and contributed to the defeat of the brutal regime that was Nazi Germany. It should also be remembered the impact on the lives of families, friends and those who knew, or even those who didn't know; the dead, missing, injured and maimed, had while in the service of their country. The effects of which spread out like ripples on a pond and are still felt to this day.

The European War was over. Attention now turned to Japan and the Far East. On 21 June 1945, 9 Squadron's Operations Record Book states a Tiger Force training syllabus had been implemented. Tiger Force would have been the RAF's contribution to the continuing bombing offensive against Japan had the atomic bomb not brought hostilities to an end in August 1945.

No 9 Squadrons long association with Bardney ended on 6 July 1945 when the squadron moved to RAF Waddington. No 189 Squadron left on 15 October and relocated to RAF Metheringham, where they disbanded on 25 November 1945. Following the departure of 189 Squadron, Bardney closed to flying but was retained for use by the Army, who used the runways to store vehicles.

Between 1959 and 1963, Bardney became a Thor Intercontinental Missile site, after which the airfield was once again closed and over the years has reverted to agriculture. Today a number of buildings, including the Watch Office, remain with model aircraft flying taking place regularly. A memorial to 9 Squadron has been erected within the village, which features a three-bladed propellor mounted on stone, which came from Kafjord in Norway.

The European War was over. Attention now turned to Japan and the Far East. On 21 June 1945, 9 Squadron's Operations Record Book states a Tiger Force training syllabus had been implemented. Tiger Force would have been the RAF's contribution to the continuing bombing offensive against Japan had the atomic bomb not brought hostilities to an end in August 1945.

No 9 Squadrons long association with Bardney ended on 6 July 1945 when the squadron moved to RAF Waddington. No 189 Squadron left on 15 October and relocated to RAF Metheringham, where they disbanded on 25 November 1945. Following the departure of 189 Squadron, Bardney closed to flying but was retained for use by the Army, who used the runways to store vehicles.

Between 1959 and 1963, Bardney became a Thor Intercontinental Missile site, after which the airfield was once again closed and over the years has reverted to agriculture. Today a number of buildings, including the Watch Office, remain with model aircraft flying taking place regularly. A memorial to 9 Squadron has been erected within the village, which features a three-bladed propellor mounted on stone, which came from Kafjord in Norway.

Bardney Today

Sources

- The Nuremberg Raid 30-31 March 1944 - Martin Middlebrook - Pen & Sword

- Royal Air Force Bomber Command Losses - 1941, 1942, 1943, 1944 and 1945 - W R Chorley - Midland Counties Publications

- Bomber Squadrons Of The RAF And Their Aircraft - Peter Moyes - Macdonald

- Bomber Command Airfields Of Lincolnshire - Peter Jacobs - Pen and Sword

- The Bomber Command War Diaries - Martin Middlebrook and Chris Everitt - Midland Publishing

- The Six Year Offensive - Ken Delve and Peter Jacobs - Arms and Armour

- An Illustrated Introduction to The Second World War - Henry Buckton - Amberley

- Lincolnshire Aviation Diary - Aviation Incidents 1930 - 1945 A P and R M Glover - Horsburgh Publishing

- Lancaster Squadrons In Focus Special Edition - Mark Postlethwaite - Red Kite

- No 9, 189 and 227 Squadron Operations Record Books - National Archives