RAF Wickenby's

War Over Europe

Written By Richard Hall

Airfield Code Letters - UI

"A movement drew my attention to the left. Lancaster PH-C for Charlie was lurching slowly out of dispersal, marshalled by an airman walking backwards, beckoning hands above his head. As the bomber swung on to the taxiway, the marshaller turned and ran for the grass, out of the aircraft's path. He stood holding up his thumbs, as Charlie lumbered past and then bent over, clasping his cap to his head, as the slipstream of the four propellers washed over him. The Lancaster moved warily along the taxiway, rudders swinging, brakes squealing and as it passed me I saw the mid-upper gunner's face behind his gun barrels. I put a thumb up and saw his gloved hand wave in reply".

(A first hand account taken from the book Lancaster Target by Jack Currie who described the above scene on his first evening at RAF Wickenby having just joined 12(B) Squadron, following his arrival from the Heavy Conversion Unit at RAF Lindholme).

"A movement drew my attention to the left. Lancaster PH-C for Charlie was lurching slowly out of dispersal, marshalled by an airman walking backwards, beckoning hands above his head. As the bomber swung on to the taxiway, the marshaller turned and ran for the grass, out of the aircraft's path. He stood holding up his thumbs, as Charlie lumbered past and then bent over, clasping his cap to his head, as the slipstream of the four propellers washed over him. The Lancaster moved warily along the taxiway, rudders swinging, brakes squealing and as it passed me I saw the mid-upper gunner's face behind his gun barrels. I put a thumb up and saw his gloved hand wave in reply".

(A first hand account taken from the book Lancaster Target by Jack Currie who described the above scene on his first evening at RAF Wickenby having just joined 12(B) Squadron, following his arrival from the Heavy Conversion Unit at RAF Lindholme).

Situated within sight of Lincoln Cathedral, although at a distance as the crow flies of just over 15 miles, land to build RAF Wickenby was first approved acquisition in May 1941. The airfield was one of many built during World War Two in Lincolnshire to facilitate Bomber Command's all-out effort to take the war to Germany, at the time the only branch of Britain's military that was capable of doing so.

|

In the winter of 1941 to 1942, the contractor McAlpine constructed Wickenby as a Class A airfield with three runways laid out as 09-27 at 2,000 yards, 04-22 and 16-34 at 1,400 yards. Construction took land from the villages of Holton and Snelland. There was also the necessity of closing the road between the two. Thirty-six hardstandings were connected to the perimeter track with the construction of a B.1 hangar near the end of the southwestern runway, a T.2 adjacent to the Technical Site to the northeast and a second T.2 on the northern extremity of the peri-track.

|

The domestic site consisted mainly of Nissen huts and, from contemporary accounts, were not the best of dwelling places to heat in the winter due to a constant lack of coke. The site was located on the eastern side of the B1399, with accommodation provided for 1,788 males and 287 females.

12(B) Squadron

In late September 1942,12(B) Squadron arrived at Wickenby from RAF Binbrook with their Vickers Wellington twin-engine bombers. Prior to flying Wellingtons, the unit had been equipped with Fairy Battles, an underpowered, poorly armed light bomber to which it had converted in February 1938 from Hawker Hinds.

On the day before war was declared, the squadron deployed to Berry-au-Bac in France as part of 76 Wing of the Advanced Air Striking Force. Their mission was to strike at the German Army should it start to advance west against Allied forces. For many months the Phoney War prevailed, in which time little activity was observed, apart from minor skirmishes. All this changed in May 1940 when the Wehrmacht launched their Blitzkrieg and drove the British, Belgium and French forces back towards the Channel coast. In a gallant attempt to stall the German advance, Fairey Battles launched low-level attacks against bridges, but due to their low speed and inadequate defensive armament, large numbers of the aircraft were shot down by flak and Luftwaffe fighters.

In late September 1942,12(B) Squadron arrived at Wickenby from RAF Binbrook with their Vickers Wellington twin-engine bombers. Prior to flying Wellingtons, the unit had been equipped with Fairy Battles, an underpowered, poorly armed light bomber to which it had converted in February 1938 from Hawker Hinds.

On the day before war was declared, the squadron deployed to Berry-au-Bac in France as part of 76 Wing of the Advanced Air Striking Force. Their mission was to strike at the German Army should it start to advance west against Allied forces. For many months the Phoney War prevailed, in which time little activity was observed, apart from minor skirmishes. All this changed in May 1940 when the Wehrmacht launched their Blitzkrieg and drove the British, Belgium and French forces back towards the Channel coast. In a gallant attempt to stall the German advance, Fairey Battles launched low-level attacks against bridges, but due to their low speed and inadequate defensive armament, large numbers of the aircraft were shot down by flak and Luftwaffe fighters.

|

The Wehrmacht was using the bridge at Veldwezelt that spanned the Albert Canal in Belgium to further their advance, and orders were given on the 12 May 1940 for 12(B) Squadron crews to attack the river crossing to deny its use. Three Battles struck the Veldwezelt bridge and were met with a hail of anti-aircraft fire, resulting in all being shot down. The lead Battle, P2204 PH-K, was flown by Flg Off D.E. Garland, with his observer Sgt T. Gray and rear gunner LAC Lawrence Reynolds.

|

The crew of P2204 were all killed in the attack. However, Garland and Gray received the Victoria Cross for their valour, the same valour as that displayed by Reynolds, but it was felt he was not part of the decision-making process, so he did not merit the award of the VC. Available evidence suggests that Garland's bombs were responsible for shattering the western truss of the bridge, so the attack was not in vain. The squadron withdrew back to RAF Finningley in mid-June 1940 and then moved to RAF Binbrook in July. Brief detachments were made by 12(B) to RAF Thorney Island and RAF Eastchurch, from where they began attacks on shipping in German-held Channel ports. Returning to RAF Binbrook in July. Brief detachments were made by 12(B) to RAF Thorney Island and RAF Eastchurch, from where they began attacks on shipping in German held Channel ports. Returning to Binbrook, the unit converted onto Wellingtons in November 1940, with training taking place during the winter months, ready for their first attack on Emden over the night of 9/10 April 1941.

|

In February 1942, Acting Air Marshall Sir Arthur Harris was appointed as Commander-in-Chief of Bomber Command. Up until that time, the results from the effort expended by the Command in bombing Germany were not reaping the results that had been expected. Harris was brought in to make the Command a more efficient force, something that he did, not without a little (unjust) controversy until the war's end. Harris was a very focused dogmatic commander and ruthlessly pursued the objectives given to him. Known as Butch Harris to his crews, he was a man who did not suffer fools and was not easily swayed in his opinions, even when ordered by his superiors to take alternative courses of action. Harris was the correct man to lead Bomber Command, and he did so with great gusto and determination, his single-mindedness often put him at odds with others, but this would certainly not have concerned Harris.

|

Soon after taking command, Harris was making plans to send a large force of bombers to Germany in what was to become known as the 1,000 Bomber Raids. He was determined to prove that his force could be a decisive weapon if suitably equipped and used in the correct way. To make his point, Harris planned to send 1,000 bombers on a single night to attack one target, the first of which was to be Cologne on 30/31 May 1942.

|

12(B) Squadron contributed 28 Wellingtons to the raid and lost 4, W5361, Z8376 and Z8643 over occupied Europe and Z8598 which crashed having exploded over Norfolk. Of the 21 crew members, only 4 survived to become POWs. The squadron remained at Binbrook, with a detachment by A and B Flights to RAF Thruxton in June/July 1942, before moving to RAF Wickenby on 25 September 1942. |

Wickenby Days

It was not long before 12(B) Squadron were in action at their new home, as on the night of 26/27 September, six Wellingtons carried out a mine laying operation (Gardening) near the Frisian Islands. Wellington III BJ776 PH-V departed at 19.30 hrs and was lost without trace. This was the first of many losses that were to be experienced at Wickenby.

Operations continued through October, with November's raids being primarily of a mine laying nature. One was flown to Hamburg on 9/10 November in which nine of the squadron's Wellingtons took part, with one aborting due to an oxygen problem, the others releasing their bombs through 10/10 cloud. The last raid in which 12(B) Squadron Wellingtons took part was on 21 November when a single aircraft, Z8407, carried out mine laying duties near Croix Island.

|

A new era in strategic bombing arrived at Wickenby on 8 November in the form of the Avro Lancaster, which gave 12(B) Squadron an increased bomb-carrying capability. Lancaster operations opened from Wickenby on 3/4 January 1943 in much the same way as the Wellingtons ended, with mine-laying sorties off Bordeaux. The Lancaster was to become the best bomber of the war, and its exploits were legendary, a far cry from its first incarnation, the Avro Manchester, which was something of a disappointment.

|

The Battle of the Ruhr

By March 1943, Harris had built up his forces to the extent that he felt the time was now right to launch sustained major attacks against German industry in the Ruhr Valley. Bomber Command did not solely concentrate on the Ruhr during this time. To have done so would have given the Luftwaffe's night fighters, flak defences and searchlights the chance to focus their efforts on defeating the attacking bombers. Instead, roughly two-thirds of the Command's efforts were targeted on the Ruhr, with the remainder scattered all over Europe, which helped disperse the defences and kept the Germans guessing.

|

The Ruhr was also in range of De Havilland Mosquitos that carried the blind bombing device known as Oboe. This electronic aid gave a better target marking accuracy and made the Command's raids more effective and efficient. The Battle of The Ruhr commenced on 5/6 March 1943 with an attack on Essen and continued until 31 July 1943 with an operation to Remscheid. At Wickenby, during this bleak time, a little enjoyment could be had by crews and ground personnel as on 1 April 1943, a dance was held to commemorate the 25th anniversary of the formation of the Royal Air Force.

|

During this time, the famous Dam Busters raid took place over the night of 16/17 May 1943. Flying from RAF Scampton 617 Squadron, commanded by Wg Cdr Guy Gibson, undertook a feat of remarkable airmanship and bravery that breached two German dams, albeit with heavy loss to the RAF crews. If you stand in the Watch Office at Wickenby, you can see aircraft in the circuit at Scampton. One wonders if those operating the tower on that night noted the Lancasters departing or their depleted return. They, of course, could not have known the raid's purpose as secrecy abounded at the time.

Throughout the Battle of the Ruhr, 12(B) Squadron, flying from Wickenby, were actively participating in the campaign and mine laying operations and sorties to Italy. During the period, the squadron lost 26 Lancasters, with 163 crew killed, 23 becoming POWs and 1 evading. These figures go to show the typical losses that Bomber Command was suffering during this very bleak period of the war.

Often you will come across graves of Bomber Command aircrew in small rural churchyards. Each is a person who had their own thoughts, emotions, fears, hopes, those who loved them and usually they died a violent death at a very young age. Two such graves can be found in the churchyard of All Saints in Holton-le-Beckering near Wickenby. Flt Sgt Eugene Salmers and Sgt J B Lindup were part of the crew of Lancaster I W4374 PH-D of 12(B) Squadron, which had taken off from Wickenby at 23.48 hrs on 17 June 1943, tasked to undertake a training flight. Just over four and half hours later, the aircraft crashed at Apley following a double engine failure, killing four crew. Salmers and Lindup were a long way from home when they died, and their loss shows the dangers of flying heavy bombers, not just from enemy action but the fickle way those items of equipment built by man can fail and lead to the untimely end to such young lives.

Throughout the Battle of the Ruhr, 12(B) Squadron, flying from Wickenby, were actively participating in the campaign and mine laying operations and sorties to Italy. During the period, the squadron lost 26 Lancasters, with 163 crew killed, 23 becoming POWs and 1 evading. These figures go to show the typical losses that Bomber Command was suffering during this very bleak period of the war.

Often you will come across graves of Bomber Command aircrew in small rural churchyards. Each is a person who had their own thoughts, emotions, fears, hopes, those who loved them and usually they died a violent death at a very young age. Two such graves can be found in the churchyard of All Saints in Holton-le-Beckering near Wickenby. Flt Sgt Eugene Salmers and Sgt J B Lindup were part of the crew of Lancaster I W4374 PH-D of 12(B) Squadron, which had taken off from Wickenby at 23.48 hrs on 17 June 1943, tasked to undertake a training flight. Just over four and half hours later, the aircraft crashed at Apley following a double engine failure, killing four crew. Salmers and Lindup were a long way from home when they died, and their loss shows the dangers of flying heavy bombers, not just from enemy action but the fickle way those items of equipment built by man can fail and lead to the untimely end to such young lives.

Hamburg

|

In July 1943, after the five-month-long campaign against the Ruhr, Harris launched Operation Gomorrah, the code name given to the bombing of Hamburg, Europe's largest port and Germany's second-largest city, which opened on 24/25 July 1943. The attack began using Pathfinder and Main Force squadrons, also for the first time, 'Window' was employed to jam Luftwaffe radars. It proved a success with 12 bombers failing to return out of a force of 791 that took part in the raid, a loss rate of 1.5%. Hamburg was to suffer by night and day as the USAAF 8th Air Force carried out attacks, which were hampered by smoke caused by Bomber Command's efforts the night before.

|

A return to Hamburg was made on 27/28 July. A warm summer night and dry conditions saw a phenomenon never before witnessed during the four years of war. A rain of high explosives and incendiaries caused a firestorm estimated to have killed between 35,000 to 45,000 people, with most of them being suffocated. Bomber crews reported seeing smoke rise to 20,000ft into the air, and it is said winds reached 120 mph at ground level. Further raids were made to Hamburg on 29/30 July, and on 2/3 August, 12(B) Squadron contributed to the attacks on the city, resulting in the loss of two Lancasters with 13 crew killed and 1 becoming a POW.

Peenemunde

|

As early as May 1943, the Allies had become aware of the existence of construction sites in Northern France for the launching of V-1 flying bombs and V-2 rockets.

The plans Hitler had to use these weapons became a priority for the Allies to defeat, and a number of operations were put into place. Operation Hydra took place over the night of 17/18 August 1943 with Bomber Command attacking the Peenemunde Army Research Centre. The aim was to destroy the research facilities and kill the scientists. |

This raid was the opening of Operation Crossbow, the Allies strategic bombing campaign against the Nazi V weapon programme. The attack on Peenemunde resulted in a seven-week delay in V weapon production but came at a loss of 40 Bomber Command aircraft, 215 crew and many foreign workers in a nearby concentration camp. Once again, 12(B) Squadron was in action to support the opening raid, losing one Lancaster with all crew.

The Autumn Raids

As the Summer turned to Autumn in 1943, the war for the Axis powers was not going well. Italy was near to surrendering, the Battle of the Atlantic was turning against the U-Boats, and the Russians had won a decisive victory at Kursk.

As the Summer turned to Autumn in 1943, the war for the Axis powers was not going well. Italy was near to surrendering, the Battle of the Atlantic was turning against the U-Boats, and the Russians had won a decisive victory at Kursk.

|

At the tail end of August, Harris decided to again mount raids against Berlin, as the nights were drawing in and the cover of darkness was needed to attack this most well-defended of cities. Accordingly, on 23/24 August, a raid to Berlin was undertaken with 12(B) Squadron losing one Lancaster with all crew.

The unit had been lucky as a total of 56 bombers were lost on this night, with the Halifax and Stirling squadrons being particularly hard hit. A loss rate of 7.9% made this the most costly raid for Bomber Command so far in the war, although the worst was yet to come. |

To give a little light relief, a new band formed at Wickenby, and they made their debut on 30 August. Named the Ad Adastras, the ensemble undoubtedly gave the station personnel a brief but welcome distraction from the daily and nightly routine that would have been prevailing at the time. Over the coming month's raids were mounted on Nuremberg, Monchengladbach, Berlin, Mannheim, Munich, Boulogne, Montlucon, Modane, Hannover, Bochum, Hagen, Kassel, Frankfurt, Stuttgart, Bremen, Leipzig, Dusseldorf, Cologne, Cannes and Ludwigshafen as well as minor operations to a variety of targets, a period of very intense operations for Bomber Command. During this period of operations from 24 August to 18 November, 12 Squadron lost 15 Lancasters with 92 crew killed and 11 becoming POWs.

October 1943 saw RAF Wickenby become a satellite to RAF Ludford Magna. In December of the same year, Ludford became the headquarters of 14 Base, also adding RAF Faldingworth to its control. On 7 November 1943, a second squadron mustered at Wickenby, 626 (coded UM) equipped with Lancaster I and IIIs, which formed from C Flight of 12(B) Squadron under the command of Wg Cdr P Haynes. The first raid undertaken by the new squadron was to Modane on 10/11 November with no losses.

The Battle of Berlin

The most significant test of the war for Bomber Command commenced on 18/19 November 1943, when an attack on the German capital Berlin was undertaken. Sir Arthur Harris had decided that Berlin should be reduced to a wasteland, and in his mind, its destruction would bring about the end of the war. For the next four and a half months, Harris more or less had a free hand in pursuing his aim of bringing about Berlin's demise. Thirty-two missions were launched during the period, sixteen to Berlin and sixteen to other large cities. Crews not only had to contend with poor winter weather and long flight distances but also a reinvigorated Luftwaffe night fighter force, who had found ways of counteracting the advantages of Window and were taking an ever-increasing toll of the Command's aircraft. From a technical perspective, new models of the navigation aid H2S were being fitted to Pathfinder aircraft, which was fortunate as the use of Oboe was out of the question due to the distance of the targets rendering it ineffective.

October 1943 saw RAF Wickenby become a satellite to RAF Ludford Magna. In December of the same year, Ludford became the headquarters of 14 Base, also adding RAF Faldingworth to its control. On 7 November 1943, a second squadron mustered at Wickenby, 626 (coded UM) equipped with Lancaster I and IIIs, which formed from C Flight of 12(B) Squadron under the command of Wg Cdr P Haynes. The first raid undertaken by the new squadron was to Modane on 10/11 November with no losses.

The Battle of Berlin

The most significant test of the war for Bomber Command commenced on 18/19 November 1943, when an attack on the German capital Berlin was undertaken. Sir Arthur Harris had decided that Berlin should be reduced to a wasteland, and in his mind, its destruction would bring about the end of the war. For the next four and a half months, Harris more or less had a free hand in pursuing his aim of bringing about Berlin's demise. Thirty-two missions were launched during the period, sixteen to Berlin and sixteen to other large cities. Crews not only had to contend with poor winter weather and long flight distances but also a reinvigorated Luftwaffe night fighter force, who had found ways of counteracting the advantages of Window and were taking an ever-increasing toll of the Command's aircraft. From a technical perspective, new models of the navigation aid H2S were being fitted to Pathfinder aircraft, which was fortunate as the use of Oboe was out of the question due to the distance of the targets rendering it ineffective.

|

In the period from August to the third week in November, heavy losses forced Harris to withdraw the Stirling from the main force. This entailed Bomber Command losing 11 squadrons of aircraft, something that could be ill afforded at this time.

Harris's aim of destroying the German capital was becoming somewhat more complex. With the withdrawal of the Stirlings, losses among Halifax II and Vs began to rise, entailing a further number of squadrons being retired from the main force. |

Harris's force had lost approximately 250 aircraft and nigh on 20% of his bomb-carrying capacity due to the removal of the Stirling and the reduction of Halifax bombers from the theatre of war. Moreover, the withdrawal of the two aircraft types put additional strain on the remaining Lancaster squadrons, who stepped up to the mark to fill the void.

The main offensive of the Battle of Berlin ran from 18/19 November to the end of January 1944, with the Command's effectiveness slowly deteriorating in the face of mounting losses and a decline in crew morale. In February and March 1944, raids were made on lesser German cities, with two more attacks taking place to Berlin before the month's end. Harris's vision of destroying the capital city had not come to fruition, with the Germans no nearer surrendering than they were at the beginning of the bombing operations. The Battle of Berlin raids ended on the night of 24/25 March 1944.

There is no question that Bomber Command had just completed its toughest test yet to date with heavy losses in aircraft and crews. A game of cat and mouse had developed between the two sides regarding each trying to get the technological advantage in night fighting techniques, countermeasures and tactics. The two squadrons from Wickenby had played their part with 12(B) Squadron losing 26 Lancasters, with 108 crew killed, 43 becoming POWs, and 5 evaded. 626 Squadron losses were 15 Lancasters, 91 killed and 9 POWs.

There is no question that Bomber Command had just completed its toughest test yet to date with heavy losses in aircraft and crews. A game of cat and mouse had developed between the two sides regarding each trying to get the technological advantage in night fighting techniques, countermeasures and tactics. The two squadrons from Wickenby had played their part with 12(B) Squadron losing 26 Lancasters, with 108 crew killed, 43 becoming POWs, and 5 evaded. 626 Squadron losses were 15 Lancasters, 91 killed and 9 POWs.

Nuremberg

Again there was to be no respite for the Bomber Command crews following the Battle of Berlin. Operations took place on 25/26 and 26/27 March to Aulnoye and Essen, respectively. On 30/31 March, Nuremberg was the target, and this raid would go down in the history of Bomber Command for all the wrong reasons. Another stamp in the record book would be made, which would make bleak reading for future historians.

|

The Main Force was sent on the 8 hour round trip to Nuremberg on 30/31 March, despite reports that weather conditions were not favourable for the raid. In total, 795 bombers were dispatched, and, in bright moonlight, the Luftwaffe's night fighters were met, which accounted for 82 of the Command's aircraft on the flight to the target. Conditions on the night also led to contrails forming, making it easier for the night fighters to see and intercept their quarry. In total, 94 aircraft were lost on the raid, Bomber Command's most significant loss on one operation of the war.

|

A further ten crashed in England, and one was written off due to severe battle damage. The bombing of Nuremberg was ineffective, and at least 120 aircraft bombed Schweinfurt, the cause of this being poor navigation brought on by poorly forecast winds.

12(B) Squadron dispatched 14 Lancasters to Nuremberg, resulting in 2 being lost, with 3 damaged, 15 crew killed, and 2 returned wounded. 626 Squadron sent 16 Lancasters with 1 returning damaged and no aircrew injuries. Although in light of the night's events, both 12(B) and 626 Squadrons had fared well, the crews, upon learning of the scale of the losses, must have breathed a sigh of relief at Wickenby as they settled in for a well-earned sleep at the end of their debriefs. It should be considered when looking at the losses sustained at Wickenby that this was being emulated across countless Bomber Command airfields in Britain. Multiply the losses up, and it is not hard to see how the final count of bomber crews who did not live to fight another day reached 55,573 by the war's end.

One of 626 Squadron's Lancasters LL849 UM-B2, which flew as part of the Nuremberg Raid, suffered not at the enemy's hands but due to the power of nature. The bomber made a precautionary landing at RAF Seething, having been struck by lightning, which just went to show the multitude of hazards that could present themselves while flying on operations.

12(B) Squadron dispatched 14 Lancasters to Nuremberg, resulting in 2 being lost, with 3 damaged, 15 crew killed, and 2 returned wounded. 626 Squadron sent 16 Lancasters with 1 returning damaged and no aircrew injuries. Although in light of the night's events, both 12(B) and 626 Squadrons had fared well, the crews, upon learning of the scale of the losses, must have breathed a sigh of relief at Wickenby as they settled in for a well-earned sleep at the end of their debriefs. It should be considered when looking at the losses sustained at Wickenby that this was being emulated across countless Bomber Command airfields in Britain. Multiply the losses up, and it is not hard to see how the final count of bomber crews who did not live to fight another day reached 55,573 by the war's end.

One of 626 Squadron's Lancasters LL849 UM-B2, which flew as part of the Nuremberg Raid, suffered not at the enemy's hands but due to the power of nature. The bomber made a precautionary landing at RAF Seething, having been struck by lightning, which just went to show the multitude of hazards that could present themselves while flying on operations.

D-Day Preparations

The first three months of 1944 had been a torrid time for Bomber Command with heavy losses among aircraft and crews, the sad outcome of this was there was little to show in the way of results for the effort expended. With D-Day in the planning stage, on 14 April, Bomber Command came under the control of Supreme Headquarters Allied Expeditionary Force (SHAEF). Bombing operations were changing from strategic to tactical. Raids were switched to targets in Occupied Europe and the transportation system in Western Germany. Harris was not all pleased that the efforts of Bomber Command were being used in such a way, but he gave his full support to the Directive he had been given. He was, however, allowed a bit of leeway as the Directive also stated, "Bomber Command will continue to be employed in accordance with their main aim of disorganizing German industry".

|

From 1 April to 6 June 1944, Bomber Command undertook raids to targets throughout Occupied Europe, Germany, and mine laying and operations supporting the Special Operations Executive (SOE). One attack on 3/4 May led to 42 Lancasters being lost, including 7 flown from Wickenby. The raid was to Mailly-Le-Camp in France, where a German military camp was situated. However, a combination of delays caused by issues with radio communications resulted in bombers circling, waiting for the order to attack.

|

The delay allowed Luftwaffe night fighters to arrive and to wreak havoc amongst the bombers. No 1 Group was hit hard, losing 28 Lancasters, including four from 12(B) Squadron with 21 crew killed, 2 becoming POW and 6 evading. 626 Squadron lost 3 Lancasters with 21 crew killed. There is no doubt that the loss of 7 Lancasters from the Wickenby Squadrons had a profound effect on the close-knit community based at the airfield, but life went on, and operations continued. The attack resulted in 1,500 tons of bombs falling on the camp, which destroyed barrack buildings, transport sheds, ammunition stores, vehicles and tanks. Operations from 1 April to 6 June resulted in 12 Squadron losing 16 Lancasters, with 57 crew killed, 7 becoming POW and 1 evading. 626 Squadron lost 10 Lancasters, with 63 crew killed, 3 becoming POW and 4 evading.

After D-Day

|

D-Day went ahead on 6 June 1944 and allowed the Allies to obtain a foothold in Europe which was in due course to enable its liberation. Bomber Command continued supporting operations, prioritised as attacks on V-weapon sites, road and rail communications, fuel depots, troop and armour concentrations/ battlefield targets. The first week after the invasion saw Bomber Command fly 2,700 sorties at night to support the landings.

|

On 14 June, the first daylight raid for over a year took place when elements of 1, 3, 5 and 8 Groups attacked German naval assets threatening Allied shipping off the Normandy beaches. The raid including participation from 617 Squadron, who utilised 12,000lb Tallboy bombs to attack concrete E-boat pens at Le Harve. Fighter cover from Spitfires of 11 Group helped ensure only one Lancaster from 15 Squadron was lost during the raid.

The British 2nd Army's breakout from the Normandy beachhead was code-named Operation Goodwood, which commenced in July. Two major raids were undertaken on 7 and 18 July to support Goodwood by Bomber Command to attack fortified villages in the Caen area. The raids resulted in the Germans being driven out but only after areas had been reduced to rubble. A force of nearly seven hundred bombers was tasked to the Normandy area to support American ground operations. Advances were quickly made through Northern France by Allied forces, stopping the Germans from mounting an effective counter-attack. Some raids were made into Germany but not to the extent that had been previously seen.

During August, further raids were undertaken in support of ground operations in the Normandy Battle Area. On the 7/8 1,019 Lancasters, Halifaxes and Mosquitos attacked aiming points in front of Allied positions. A similar raid took place on 14 August, but on this occasion, bombs landed among Canadian troops killing 13 and injuring 53. This shows the difficulty of precision bombing with the tools then available to Bomber Command, who was more of a strategic rather than a tactical force.

For the period of operations from 7 June to 15 August 1944, 12(B) Squadron lost 13 Lancasters, with 63 crew killed, 12 becoming POWs and 4 evading. 626 Squadron lost 8 Lancasters, with 37 crew killed, 9 POWs and 5 evading.

During August, further raids were undertaken in support of ground operations in the Normandy Battle Area. On the 7/8 1,019 Lancasters, Halifaxes and Mosquitos attacked aiming points in front of Allied positions. A similar raid took place on 14 August, but on this occasion, bombs landed among Canadian troops killing 13 and injuring 53. This shows the difficulty of precision bombing with the tools then available to Bomber Command, who was more of a strategic rather than a tactical force.

For the period of operations from 7 June to 15 August 1944, 12(B) Squadron lost 13 Lancasters, with 63 crew killed, 12 becoming POWs and 4 evading. 626 Squadron lost 8 Lancasters, with 37 crew killed, 9 POWs and 5 evading.

Turning Point

The Allies made quick progress after they broke through the German defences in Normandy. Paris was liberated on 24 August, and Belgium entered in September, which yielded the vital port of Antwerp shortly after. On 14 September, Harris was released from his control by SHAEF, and Bomber Command reverted back to the Air Ministry, with the caveat it was to remain ready to answer any calls for assistance from ground forces as they moved towards Germany.

|

On 16/17 September, Bomber Command's supported British and American airborne forces at Arnhem and Nijmegen, which was part of an operation known as Market Garden. This ultimately failed due to the Allies overextending themselves and with stiffer resistance than anticipated being met. Any chance of the war being over by Christmas had now evaporated.

Harris had no problem with providing this kind of support and remained ready to respond as required. But this only committed a small part of his now considerable force, so what was the best way to employ Bomber Command and make the best use of this valuable resource? |

Three schools of thought were prevailing at the time: attacks on synthetic oil production, the German transportation system, and a less favoured option of a return to the strategic bombing of German industrial cities. However, a directive issued on 25 September to both Bomber Command and the American 8th Air Force made it clear that the oil option had won with a secondary objective to attack the German rail, waterway transport system and also tank and vehicle production. Later in the Directive, it stated that when weather or tactical conditions precluded operations on the primary targets, German cities were cited for general attack. This gave Harris all he needed to continue with his raids on the cities as he did not feel attacks on the oil industry were the best use of the force at his disposal. However, many of the areas targeted were associated with oil production.

During this time, Bomber Command's strength continued to grow, bombing aids improved, and electronic measures were further implemented to outwit the Germans. Even cloud cover now failed to protect their cities. The Luftwaffe night fighter force was in decline, and bomber casualties were reducing. The scene was set that was to lead to the ultimate victory. Bomber Command ranged far and wide to targets that included Brunswick, Nuremberg, the Ruhr, Darmstadt, Bremerhaven, Bonn, Freiburg, Heilbronn and Ulm. Crews flew by day and night, their logbooks showing attacks on a variety of targets which encompassed gun batteries in France, the Dortmund Ems Canal, obscure German rail yards and even the Tirpitz, which was ultimately sunk in a Norwegian Fjord. The extent of the raids can be seen in that 46% of the total tonnage of bombs dropped by the Command would be in the last nine months of the war.

One of the Lancasters flying at this time with 12(B) Squadron was ND342 PH-U. The bomber was fitted with 0.5 calibre machine guns in a rear-mounted Rose Turret. The majority of Lancasters were armed with .303 calibre guns, but it was long known that the range and effectiveness of such guns were limited, especially against cannon-armed fighters. As the war progressed, the Rose Turret was fitted to some Lancasters to provide better defensive firepower. ND342 was lost on a raid to Essen on 12/14 December 1944, with four crew being killed and three becoming POWs.

During this time, Bomber Command's strength continued to grow, bombing aids improved, and electronic measures were further implemented to outwit the Germans. Even cloud cover now failed to protect their cities. The Luftwaffe night fighter force was in decline, and bomber casualties were reducing. The scene was set that was to lead to the ultimate victory. Bomber Command ranged far and wide to targets that included Brunswick, Nuremberg, the Ruhr, Darmstadt, Bremerhaven, Bonn, Freiburg, Heilbronn and Ulm. Crews flew by day and night, their logbooks showing attacks on a variety of targets which encompassed gun batteries in France, the Dortmund Ems Canal, obscure German rail yards and even the Tirpitz, which was ultimately sunk in a Norwegian Fjord. The extent of the raids can be seen in that 46% of the total tonnage of bombs dropped by the Command would be in the last nine months of the war.

One of the Lancasters flying at this time with 12(B) Squadron was ND342 PH-U. The bomber was fitted with 0.5 calibre machine guns in a rear-mounted Rose Turret. The majority of Lancasters were armed with .303 calibre guns, but it was long known that the range and effectiveness of such guns were limited, especially against cannon-armed fighters. As the war progressed, the Rose Turret was fitted to some Lancasters to provide better defensive firepower. ND342 was lost on a raid to Essen on 12/14 December 1944, with four crew being killed and three becoming POWs.

|

The war was drawing near to ending, but Hitler still had some surprises up his sleeve. In December 1944, the Germans launched their last offensive in the west with an attack through the Ardennes, which caught the Allies completely off guard. The plan was to drive an attack through to the port of Antwerp, thus cutting off the Allied supply route.

|

Bad weather hampered Allied air operations, and in what was to become known as the Battle of the Bulge, initial advances were made, but the Allies prevailed and pushed the offensive back. As weather conditions improved, Bomber Command aircraft equipped with the new blind bombing aid G-H struck at enemy troop positions in Belgium and rail infrastructure behind the battlefront. This impeded the Germans from moving reinforcements and ultimately led to Hitler's last gamble in the west failing. The Germans capacity to fight was now severely depleted, and they were unable to make good their losses. As the end of the year approached, most of Germany's major cities lay in ruins, the Ruhr continued to be attacked, the Allies and the Russians were advancing. However, Hitler and his henchmen showed no signs of surrendering, despite the suffering of the German people.

On 22 December 1944, an incident occurred at Wickenby that showed it was not just enemy action that could result in the death of a bomber crew. Lancaster I NG244 UM-E2 of 626 Squadron took off from the airfield as part of a raid to Koblenz. One of the bomber's engines failed on the outward leg, which necessitated a return to base. As the Lancaster approached Wickenby, the pilot was confronted by poor weather and visibility. The aircraft was diverted to RAF Leeming in Yorkshire, but while turning in the circuit, no doubt at low height, a second engine failed, giving the pilot little time to react. The Lancaster crashed into the bomb dump, killing all on board. A combination of engineering, weather and bad luck had contributed to the loss of another brave crew. Luckily the bomb dump did not explode. Air and ground crew alike made frantic efforts to get as much ordnance away from the burning bomber as possible, as had the bomb dump exploded, it would have likely taken the airfield and local villages with it. All 12 and 626 Squadron aircraft were diverted to other destinations on their return from Koblenz. Wickenby remained out of action for some time after.

During the period of operations from 15 August to 31 December 1944, 12(B) Squadron lost 11 Lancasters, with 59 crew killed, 12 becoming POWs and 4 evading. 626 Squadron lost 11 Lancasters, with 59 crew killed, 9 becoming POWs and 5 evading.

On 22 December 1944, an incident occurred at Wickenby that showed it was not just enemy action that could result in the death of a bomber crew. Lancaster I NG244 UM-E2 of 626 Squadron took off from the airfield as part of a raid to Koblenz. One of the bomber's engines failed on the outward leg, which necessitated a return to base. As the Lancaster approached Wickenby, the pilot was confronted by poor weather and visibility. The aircraft was diverted to RAF Leeming in Yorkshire, but while turning in the circuit, no doubt at low height, a second engine failed, giving the pilot little time to react. The Lancaster crashed into the bomb dump, killing all on board. A combination of engineering, weather and bad luck had contributed to the loss of another brave crew. Luckily the bomb dump did not explode. Air and ground crew alike made frantic efforts to get as much ordnance away from the burning bomber as possible, as had the bomb dump exploded, it would have likely taken the airfield and local villages with it. All 12 and 626 Squadron aircraft were diverted to other destinations on their return from Koblenz. Wickenby remained out of action for some time after.

During the period of operations from 15 August to 31 December 1944, 12(B) Squadron lost 11 Lancasters, with 59 crew killed, 12 becoming POWs and 4 evading. 626 Squadron lost 11 Lancasters, with 59 crew killed, 9 becoming POWs and 5 evading.

Towards Victory

Official History HMSO 1961 - In the last year of the war Bomber Command played a major part in the complete destruction of whole vital segments of German oil production, in the virtual dislocation of her communications system and in the elimination of other important activities.

Official History HMSO 1961 - In the last year of the war Bomber Command played a major part in the complete destruction of whole vital segments of German oil production, in the virtual dislocation of her communications system and in the elimination of other important activities.

|

The last major attack by the Luftwaffe took place on 1 January 1945 and supported the Battle of the Bulge. Operation Bodenplatt was planned to catch the Allies aircraft off guard and gain air superiority to allow the stalled advance of the German Army and Waffen SS on the battlefield to continue. |

The attack was a surprise, and many Allied aircraft were lost on the ground. However, the operation was ultimately a failure, with the Luftwaffe losing many machines and, more crucially, pilots, which could not be replaced at this stage of the war.

Harris now had a strength of over 1,400 aircraft, which at its peak would reach 1,625 bombers, most of them Lancasters. Losses continued to fall due to the overwhelming air superiority held by Allied airpower. Over the coming months, Bomber Command, in conjunction with the American 8th Air Force, systematically reduced Germany's capacity to fight by pounding them by day and night.

Precision attacks on bridges and viaducts by 9 and 617 Squadrons utilised Bomber Command's latest weapon known as the Grand Slam, which weighed in at 22,000lb and required specially modified Lancasters flown by 617 to carry the ordnance. Main Force raids continued against rail centres, marshalling yards, canals and aqueducts, while Fighter Command and fighters of the American 8th Air Force shot up anything that moved on the ground or didn't move for that matter. At Wickenby on 13 January 1945, an explosion in one of the bomb dump's fuzing sheds caused the death of three armourers, another instance where it was not just the enemy that could inflict casualties.

In February, Bomber Command was ordered to take part in Operation Thunderclap. A series of raids on major communication centres immediately behind the Eastern Front were planned, packed with refugees fleeing from the Russians and wounded troops. It was envisaged such attacks would produce transport and communication problems on a massive scale and aid the advance of the Russians westward, with a view that it would hasten the war's end. Stalin put pressure on Churchill to assist the Russian forces, and the British Prime Minister was keen to use Allied heavy bombers to achieve this end. Opposition from his own ministers failed to deter Churchill, who ordered plans to be drawn up to attack Berlin, Chemnitz, Dresden and Leipzig.

Harris now had a strength of over 1,400 aircraft, which at its peak would reach 1,625 bombers, most of them Lancasters. Losses continued to fall due to the overwhelming air superiority held by Allied airpower. Over the coming months, Bomber Command, in conjunction with the American 8th Air Force, systematically reduced Germany's capacity to fight by pounding them by day and night.

Precision attacks on bridges and viaducts by 9 and 617 Squadrons utilised Bomber Command's latest weapon known as the Grand Slam, which weighed in at 22,000lb and required specially modified Lancasters flown by 617 to carry the ordnance. Main Force raids continued against rail centres, marshalling yards, canals and aqueducts, while Fighter Command and fighters of the American 8th Air Force shot up anything that moved on the ground or didn't move for that matter. At Wickenby on 13 January 1945, an explosion in one of the bomb dump's fuzing sheds caused the death of three armourers, another instance where it was not just the enemy that could inflict casualties.

In February, Bomber Command was ordered to take part in Operation Thunderclap. A series of raids on major communication centres immediately behind the Eastern Front were planned, packed with refugees fleeing from the Russians and wounded troops. It was envisaged such attacks would produce transport and communication problems on a massive scale and aid the advance of the Russians westward, with a view that it would hasten the war's end. Stalin put pressure on Churchill to assist the Russian forces, and the British Prime Minister was keen to use Allied heavy bombers to achieve this end. Opposition from his own ministers failed to deter Churchill, who ordered plans to be drawn up to attack Berlin, Chemnitz, Dresden and Leipzig.

|

On 3 February, the USAAF bombed Berlin. On 13/14 February, Bomber Command raided Dresden in what was to become one of the most controversial attacks of the war, which still causes argument to this day. Dresden was targeted in two waves, the second of which caused a firestorm that consumed an estimated 25,000 people. It is considered that this raid unfairly turned opinion against Bomber Command, Harris and his crews. No medal was struck for the Command at the war's end, which caused resentment from the crews for many years until this was addressed, partially, by the awarding in 2013 of a Bomber Command clasp.

|

Veterans saw the clasp as an insult for their sacrifices, and many never claimed the award. Harris was following the orders he'd been given, but when the chips were down, and he needed the support of Churchill, this was denied and can be seen very much as a betrayal and the scapegoating of Bomber Command's Commander In Chief and his brave crews; a very sorry episode indeed. Further raids were carried in February leading into March, and it was on 16/17 during a raid to Nuremberg, the Luftwaffe night fighters showed they were still capable of exacting a heavy toll. During this raid, 24 Lancasters were brought down, which for Wickenby, included 5 from 12(B) Squadron and 1 from 626 Squadron. Even at this late stage of the war, misery and loss came to haunt the Lincolnshire airfield at a time when most crews considered they might just survive.

Operation Gisela

|

At this point of the war, there was not much of a threat expected from the Luftwaffe, especially over England. However, this idea was dispelled on 3/4 March 1945 when intruders (Luftwaffe night fighters) were in action over England as part of Operation Gisela. Over 140 Luftwaffe crews were briefed to carry out a mass intruder mission. The operation aimed to attack RAF bombers as they returned to their home airfields, a time when crews were likely to be relaxing and therefore off their guard following a long and arduous trip.

|

Two Lancaster IIIs, ME323 PH-P and PB476 PH-Y from 12 Squadron, were on local training flights when they were shot down in Lincolnshire by Junkers Ju88s, with the loss of all crew. PB476 was on a night navigational exercise when the intruder struck at 00.29hrs and severely damaged the bomber with cannon fire. The Lancaster dived vertically into the ground near Driby Top at Weekly Cross. ME323 was shot down at 01.10hrs and crashed between Stockwith and Blyton.

In total 23 bombers and 1 Mosquito were brought down by the intruders, with a further 20 aircraft damaged. However, the Luftwaffe didn't have it all their own way, with 8 night fighters failing to return. This type of action by the Luftwaffe was highly effective and, had it been more consistent, could have had a significant effect on the RAF's operations. Luckily Hitler intervened and decreed that intruder operations over Britain should be limited as he wanted the German populace to see RAF bombers being shot down over the homeland, where he considered this would help bolster morale; once again, Hitler's flawed thought processes ignored best military practice for the sake of his own views.

The End in Sight

Raids in March continued to a variety of targets, including shipyards, U-boat pens, railway yards, bridges, and the few remaining oil plants. On 25 March 1945, one of 12(B) Squadron's Lancasters, ME758 PH-N 'Nan', completed her 100th operational sortie, achieving 108 before the war's end.

The last losses for the Wickenby squadrons occurred on 4/5 April 1945. A raid was undertaken to the synthetic oil plant at Lutzkendorf, during which Lancaster I RF182 PH-P of 12(B) Squadron was lost with all crew. In addition, two 626 Squadron Lancasters failed to return from the raid, these being MK I PD295 UM-B2 and MK III PB411 UM-Y2, both with the loss of all crew.

In total 23 bombers and 1 Mosquito were brought down by the intruders, with a further 20 aircraft damaged. However, the Luftwaffe didn't have it all their own way, with 8 night fighters failing to return. This type of action by the Luftwaffe was highly effective and, had it been more consistent, could have had a significant effect on the RAF's operations. Luckily Hitler intervened and decreed that intruder operations over Britain should be limited as he wanted the German populace to see RAF bombers being shot down over the homeland, where he considered this would help bolster morale; once again, Hitler's flawed thought processes ignored best military practice for the sake of his own views.

The End in Sight

Raids in March continued to a variety of targets, including shipyards, U-boat pens, railway yards, bridges, and the few remaining oil plants. On 25 March 1945, one of 12(B) Squadron's Lancasters, ME758 PH-N 'Nan', completed her 100th operational sortie, achieving 108 before the war's end.

The last losses for the Wickenby squadrons occurred on 4/5 April 1945. A raid was undertaken to the synthetic oil plant at Lutzkendorf, during which Lancaster I RF182 PH-P of 12(B) Squadron was lost with all crew. In addition, two 626 Squadron Lancasters failed to return from the raid, these being MK I PD295 UM-B2 and MK III PB411 UM-Y2, both with the loss of all crew.

|

Nuisance raids by Mosquito aircraft continued on Berlin, with the last major attack by five hundred and twelve heavies taking place on Potsdam on 14/15 April. Much of Germany had been overrun by this time, but ports still needed to be captured. To facilitate this, Bomber Command attacked the Island of Heligoland on 18 April, which guarded the approach to Hamburg and also the coastal batteries at Wangerooge, defending the ports of Bremen and Wilhelmshaven.

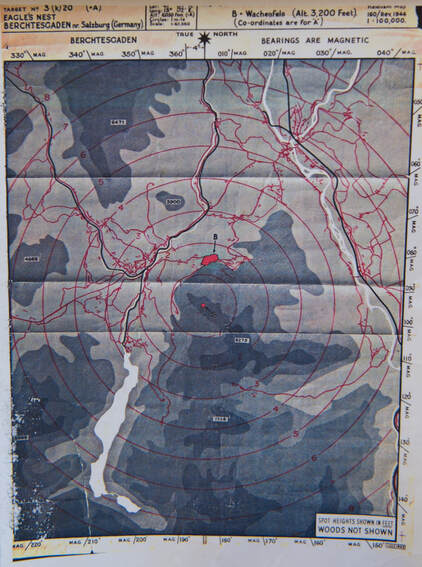

Wickenby's squadrons flew their final mission on 25 April 1945 to Berchtesgaden, Hitler's Eagle's Nest and the local SS Guards barracks. The last raid by the RAF's heavy bombers took place on 25/26 April to an oil refinery at Tonsberg in Norway. Following this, Bomber Command went onto more peaceful operations of repatriation of prisoners of war and the dropping of food supplies (Operation Manna) to starving Dutch civilians. |

The end of April 1945 saw some very significant events occurring. On the 12th, President Roosevelt died to be succeeded by Harry Truman. The 28th saw Benito Mussolini killed by Italian partisans, and two days later, Hitler, with his long term partner and now wife Eva Braun, committed suicide in his bunker in Berlin. Grand Admiral Karl Donitz succeeded him.

The very last operation flown by Bomber Command was on 2/3 May when Mosquitos of 8 Group and Halifax of 100 Group raided shipping at Kiel. Even at this late stage, losses continued, with one Mosquito and two Halifax failing to return. After just under six years, the war was finally over for Bomber Command.

During the period of operations from 1 January to 3 May 1945, 12 Squadron lost 17 Lancasters, with 91 crew killed and 20 becoming POWs. 626 Squadron lost 11 Lancasters, with 64 crew killed and 2 becoming POWs.

The very last operation flown by Bomber Command was on 2/3 May when Mosquitos of 8 Group and Halifax of 100 Group raided shipping at Kiel. Even at this late stage, losses continued, with one Mosquito and two Halifax failing to return. After just under six years, the war was finally over for Bomber Command.

During the period of operations from 1 January to 3 May 1945, 12 Squadron lost 17 Lancasters, with 91 crew killed and 20 becoming POWs. 626 Squadron lost 11 Lancasters, with 64 crew killed and 2 becoming POWs.

Surrender

|

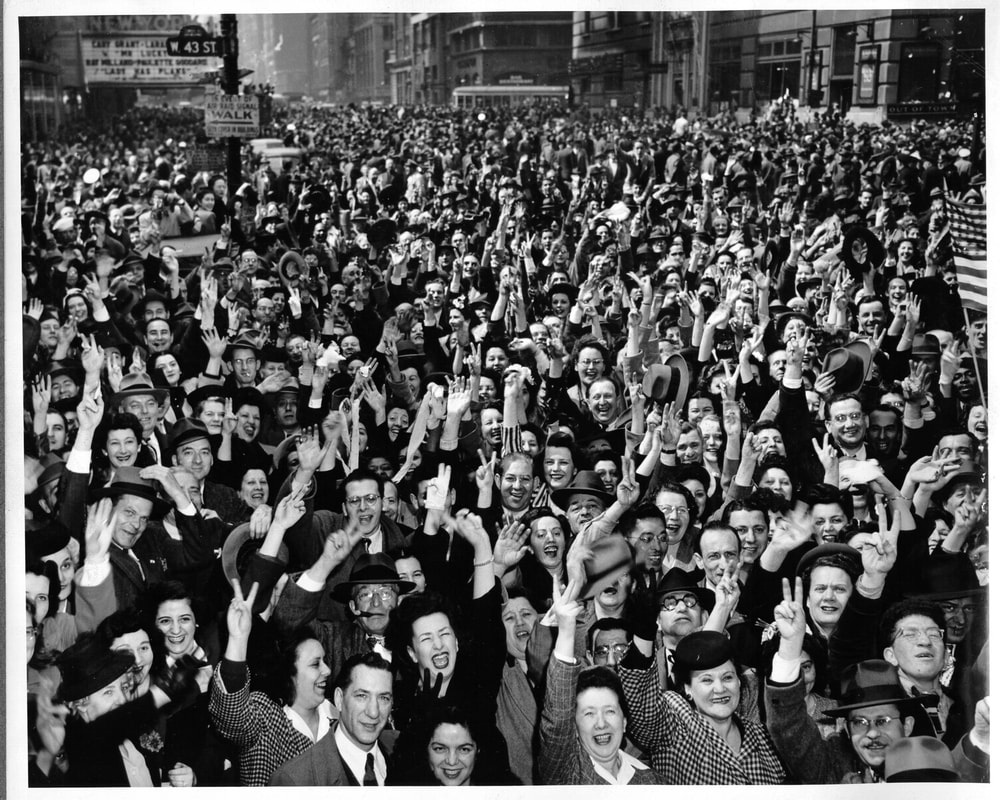

On 8 May 1945, the war in Europe ended with the signing of a document entitled the German Instrument of Surrender. Its terms dictated the total unconditional surrender of Germany, and the day itself became known as Victory In Europe Day (VE Day). RAF Wickenby was just one airfield of the many that took part in Bomber Command's campaign over Europe. Nonetheless, it would have experienced the whole range of human emotions; fear, sorrow, anger, despair, hope, joy and sadness that goes with groups of people who did not know if they or their loved ones would live to see another day.

|

Yet despite this, all those stationed at Wickenby got on with their jobs and contributed to the defeat of the brutal regime that was Nazi Germany. It should also be remembered the impact on the lives of families, friends and those who knew, or even those who didn't know; the dead, missing, injured and maimed, had while in the service of their country. The effects of which spread out like ripples on a pond and are still felt to this day.

Post War

With the war in Europe at an end, 12(B) Squadron left Wickenby and returned to RAF Binbrook in September 1945. 626 Squadron disbanded on 14 October 1945, but aerial activity was not quite at an end. 109 Squadron flying De Havilland Mosquitos XVIs, briefly came to the airfield arriving in October and departing to RAF Hemswell on 26 November 1945.

In December, Wickenby was handed over to 40 Group Maintenance Command as a sub-site of 61 Maintenance Unit (MU). Later, 93 MU was established at the airfield. Their task was to collect ordnance from other disused airfields and store it on the runways whilst awaiting disposal. September 1952 saw the arrival of 92 MU, their job to supply munitions to units in north Lincolnshire until their disbandment in early 1956.

Between 1964 to 1966, much of the site was sold off, with the land returning to agriculture. The road from Snelland to Holton-cum-Beck, closed for construction of the airfield, was reinstated.

Civil/private flying continued at Wickenby and does so to this day with many light aircraft based at the airfield. In 1968 Miller Aerial Spraying arrived from Skegness with Piper Super Cub and Pawnee aircraft, although they are no longer in residence.

With the war in Europe at an end, 12(B) Squadron left Wickenby and returned to RAF Binbrook in September 1945. 626 Squadron disbanded on 14 October 1945, but aerial activity was not quite at an end. 109 Squadron flying De Havilland Mosquitos XVIs, briefly came to the airfield arriving in October and departing to RAF Hemswell on 26 November 1945.

In December, Wickenby was handed over to 40 Group Maintenance Command as a sub-site of 61 Maintenance Unit (MU). Later, 93 MU was established at the airfield. Their task was to collect ordnance from other disused airfields and store it on the runways whilst awaiting disposal. September 1952 saw the arrival of 92 MU, their job to supply munitions to units in north Lincolnshire until their disbandment in early 1956.

Between 1964 to 1966, much of the site was sold off, with the land returning to agriculture. The road from Snelland to Holton-cum-Beck, closed for construction of the airfield, was reinstated.

Civil/private flying continued at Wickenby and does so to this day with many light aircraft based at the airfield. In 1968 Miller Aerial Spraying arrived from Skegness with Piper Super Cub and Pawnee aircraft, although they are no longer in residence.

Wickenby Today

|

Unlike many former Bomber Command airfields in Lincolnshire, Wickenby remains active. There is a flying club present, and the former Watch Office serves as a clubhouse and cafe (now closed). It also houses the superb RAF Wickenby Memorial Collection on the upper floor. A vast amount of information and displays can be seen relating to 12(B) and 626 Squadrons. It is very easy to lose track of time as you immerse yourself in the atmosphere of the Tower as the artefacts and writings take you back to times past and those who came before. There is also the chance to see aerial activity from the Tower as light aircraft come and go on Wickenby's remaining runways.

|

|

The Memorial Collection originates from the Wickenby Register formed in 1979 by a small group of aircrew who served with 12(B) and 626 Squadrons. Over the following years, the two squadrons were researched, information was collated, photographs obtained, and artefacts tracked down for safekeeping.

The assemblage forms the basis of the Wickenby Archive, which is now looked after and added to by the RAF Wickenby Memorial Collection. |

The Register was also responsible for creating the Memorial, which can be seen at the entrance to the airfield and its refurbishment in 2010, as well as the creation of the Book of Remembrance housed in the museum.

The Wickenby Register was disbanded in September 2011, and a new committee was set up, named the Friends of the Wickenby Archive. The committee represents the Airfield, the Wickenby Register and the RAF Wickenby Memorial Collection. Their responsibilities are to maintain the memory of Wickenby's two squadrons, the safeguarding of the Archive and the Book Of Remembrance, the maintenance of the Memorial and the arranging of an annual memorial service.

For further information click the following link for the museum's website - www.wickenbymuseum.co.uk

The Wickenby Register was disbanded in September 2011, and a new committee was set up, named the Friends of the Wickenby Archive. The committee represents the Airfield, the Wickenby Register and the RAF Wickenby Memorial Collection. Their responsibilities are to maintain the memory of Wickenby's two squadrons, the safeguarding of the Archive and the Book Of Remembrance, the maintenance of the Memorial and the arranging of an annual memorial service.

For further information click the following link for the museum's website - www.wickenbymuseum.co.uk

RAF Wickenby's Icarus Memorial

Jack Currie DFC

|

In mid-1943, a newly qualified bomber pilot arrived at Wickenby. His name was Jack Currie. He completed a tour of operations at Wickenby, flying with C Flight of 12(B) Squadron for the first time on 3 July 1943 as second pilot on a raid to Cologne, before moving to 626 Squadron upon its formation in November 1943.

After the war, neither Bomber Command or its crews and personnel got the recognition deserved to those who had sacrificed so much. However, Jack Currie went some way in the 1970s and 80s in addressing this by writing several books detailing his experiences and that of other crews who took part in the RAF's bombing campaign, as well as featuring in a number of aviation-related television documentaries, which included The Watch Tower and The Lancaster Legend. |

Jack's book Lancaster Target is written to give the reader a first-hand account of just what it was like to fly from Wickenby on some of the war's most demanding operations. Jack wrote this book with a warmth and humour that belies the extreme peril he and his crew faced on a daily basis.

Jack Currie was only one of many who flew from Wickenby. However, his books and documentaries helped keep the memories of Bomber Command alive at a time when most were forgetting. For this, we must give him due credit, as his work has left a long-lasting impression on those who came after.

Jack Currie was only one of many who flew from Wickenby. However, his books and documentaries helped keep the memories of Bomber Command alive at a time when most were forgetting. For this, we must give him due credit, as his work has left a long-lasting impression on those who came after.

Wickenby's Wartime Remains

As with many wartime airfields some of the past remains in place and Wickenby is no exception. There follows a selection of photos of some of the airfield's buildings that remain in-situ. All Images Richard Hall.

As with many wartime airfields some of the past remains in place and Wickenby is no exception. There follows a selection of photos of some of the airfield's buildings that remain in-situ. All Images Richard Hall.

Sources

- Lancaster Target - Jack Currie - Goodall

- The Nuremberg Raid 30/31 March 1944 - Martin Middlebrook - Pen & Sword

- Royal Air Force Bomber Command Losses - 1941, 1942, 1943, 1944 and 1945 - W R Chorley - Midland Counties Publications

- RAF Wickenby Memorial Collection

- The Six Year Offensive - Ken Delve and Peter Jacobs - Arms & Armour

- An Illustrated Introduction to The Second World War - Henry Buckton - Amberley

- Luftwaffe Night Fighter Combat Claims 1939 - 1945 - John Foreman, Johannes Matthews and Simon Parry - Red Kite

- Lincolnshire Aviation Diary - Aviation Incidents 1930 - 1945 A P and R M Glover - Horsburgh Publishing

- Lancaster Squadrons In Focus Special Edition - Mark Postlethwaite - Red Kite