RAF Greenham Common

USAAF Station 486

Written by Richard Hall

“Soldiers, Sailors and Airmen of the Allied Expeditionary Force!”

“You are about to embark upon the Great Crusade, toward which we have striven these many months. The eyes of the world are upon you. The hopes and prayers of liberty-loving people everywhere march with you. In company with our brave Allies and brothers-in-arms on other Fronts, you will bring about the destruction of the German war machine, the elimination of Nazi tyranny over the oppressed peoples of Europe, and security for ourselves in a free world.”

“Your task will not be an easy one. Your enemy is well trained, well equipped and battle hardened. He will fight savagely. But this is the year 1944! Much has happened since the Nazi triumphs of 1940-41. The United Nations have inflicted upon the Germans great defeats, in open battle, man-to-man. Our air offensive has seriously reduced their strength in the air and their capacity to wage war on the ground. Our Home Fronts have given us a superiority in weapons and munitions of war, and placed at our disposal great reserves of trained fighting men. The tide has turned! The free men of the world marching together to Victory!”

“I have full confidence in your devotion to duty and skills in battle. We will accept nothing less than full Victory!”

“Good Luck! And let us all beseech blessing of Almighty God upon this great and noble undertaking.”

Signed: General Dwight D. Eisenhower

“You are about to embark upon the Great Crusade, toward which we have striven these many months. The eyes of the world are upon you. The hopes and prayers of liberty-loving people everywhere march with you. In company with our brave Allies and brothers-in-arms on other Fronts, you will bring about the destruction of the German war machine, the elimination of Nazi tyranny over the oppressed peoples of Europe, and security for ourselves in a free world.”

“Your task will not be an easy one. Your enemy is well trained, well equipped and battle hardened. He will fight savagely. But this is the year 1944! Much has happened since the Nazi triumphs of 1940-41. The United Nations have inflicted upon the Germans great defeats, in open battle, man-to-man. Our air offensive has seriously reduced their strength in the air and their capacity to wage war on the ground. Our Home Fronts have given us a superiority in weapons and munitions of war, and placed at our disposal great reserves of trained fighting men. The tide has turned! The free men of the world marching together to Victory!”

“I have full confidence in your devotion to duty and skills in battle. We will accept nothing less than full Victory!”

“Good Luck! And let us all beseech blessing of Almighty God upon this great and noble undertaking.”

Signed: General Dwight D. Eisenhower

General Dwight D Eisenhower spoke the immortal words above at Greenham Common, the day before the invasion of Europe, D-Day, which was launched on 6 June 1944.

Situated close to the Berkshire town of Newbury, Greenham Common lies on a ridge 380ft (116m) above sea level on an area of scrubland. The site was first surveyed in early 1941 as a satellite for the proposed Bomber Command Operational Training Unit (OTU) airfield that was to be built at RAF Aldermaston. Greenham was constructed to the standard OTU pattern with the main runway 11-29 at 4,800ft (1,463m), 03-21 at 3,300ft (1,005m) and 14-32 at 4,053ft (1,235m). Extensions to 11-29 and 14-32 saw both being lengthened to 5988ft (1825m) and 4,200ft (1,280m) respectively. The airfield was provided with 27 pans and 25 loops and two T.2 hangars erected near the technical site.

Building the airfield entailed several minor roads being closed that ran across the Common. The main Basingstoke to Newbury road also encroached onto the dispersal area and the technical site. To overcome this, the road was fitted with barriers and guard huts to control access and deny passage during aircraft movements. To the south/east, a small instructional site was constructed near the main road and further out to the north/east, the bomb dump, WAAF quarters (located around Bowdon House and Grove Cottage) and the sewerage works. Seven dispersed sites were built, which it was considered would cater to around 2,300 service personnel.

As the airfield neared completion in the summer of 1942, it became clear that Greenham would not become an OTU for Bomber Command, as there was a need for airfields for the United States Army Air Force (USAAF), who were mustering in Britain to take the war to the Third Reich and the eventual invasion of Europe. The United States entered the war following the Japanese attack at Pearl Harbour on 7 December 1941, which was followed by Hitler declaring war on America on 11 December of the same year.

Situated close to the Berkshire town of Newbury, Greenham Common lies on a ridge 380ft (116m) above sea level on an area of scrubland. The site was first surveyed in early 1941 as a satellite for the proposed Bomber Command Operational Training Unit (OTU) airfield that was to be built at RAF Aldermaston. Greenham was constructed to the standard OTU pattern with the main runway 11-29 at 4,800ft (1,463m), 03-21 at 3,300ft (1,005m) and 14-32 at 4,053ft (1,235m). Extensions to 11-29 and 14-32 saw both being lengthened to 5988ft (1825m) and 4,200ft (1,280m) respectively. The airfield was provided with 27 pans and 25 loops and two T.2 hangars erected near the technical site.

Building the airfield entailed several minor roads being closed that ran across the Common. The main Basingstoke to Newbury road also encroached onto the dispersal area and the technical site. To overcome this, the road was fitted with barriers and guard huts to control access and deny passage during aircraft movements. To the south/east, a small instructional site was constructed near the main road and further out to the north/east, the bomb dump, WAAF quarters (located around Bowdon House and Grove Cottage) and the sewerage works. Seven dispersed sites were built, which it was considered would cater to around 2,300 service personnel.

As the airfield neared completion in the summer of 1942, it became clear that Greenham would not become an OTU for Bomber Command, as there was a need for airfields for the United States Army Air Force (USAAF), who were mustering in Britain to take the war to the Third Reich and the eventual invasion of Europe. The United States entered the war following the Japanese attack at Pearl Harbour on 7 December 1941, which was followed by Hitler declaring war on America on 11 December of the same year.

The first occupants to arrive at the airfield were the HQ staff of the 51st Troop Carrier Wing, who crossed the Atlantic in September 1942 and stayed at Greenham until November of the same year before leaving to take part in Operation Torch, the Anglo/American invasion of North Africa.

|

Following the USAAF’s departure, the airfield was transferred from 92 (Bomber) Group to 70 Group RAF, with flying commencing the following month. The first unit to arrive was 15 (Pilot) Advanced Flying Unit (15 (P) (AFU), who brought their Airspeed Oxfords in from RAF Andover. On 28 April 1943, they were joined by the Oxfords of 1511 (BAT) Flight, both units staying until September of the same year, when the Americans acquired the airfield, becoming USAAF Station 486 on 1 October 1943.

|

|

Greenham was handed over to the VIII Air Support Command on 8 November 1943. Their first task was to equip the 354th Fighter Group of the Ninth Air Force (9th AF) with North American Mustang P-51Bs, the first Rolls-Royce Merlin-powered variants of the type to enter service in the European theatre. The 354th stayed for a week before leaving for Boxted on 13 November, where they provided long-range escort to the bombers of the Eighth Air Force, who were in desperate need of fighter protection as they flew operations deeper into Germany.

|

|

Following on, a number of 9th AF units passed through Greenham, including the HQ of the 70th Fighter Wing (FW), the HQ of the 100th FW and the HQ of the 71st FW whose 368th Fighter Group, consisting of the 395th, 396th and 397th Fighter Squadrons, began working up at the airfield with their Republic P-47D Thunderbolts.

The squadron’s first combat mission took place on 14 March 1944, when 48 Thunderbolts flew an operation to the French coastline. |

The 368th was under notice to quit Greenham as the airfield was required by IX Troop Carrier Command (TCC), and they duly moved out to Station 404 at Chilbolton on 15 March 1944, with elements of 438th Troop Carrier Group (TCG) arriving the next day. To the east lay Crookham Common and this area was earmarked for the assembly of Waco assault gliders, which came across the Atlantic in packing cases. Once assembled, the gliders were towed from Greenham for delivery to other airfields. On average 15 gliders, a day were being produced by the spring of 1944, this figure increasing to 50 a day by September of the same year. Steel track was also laid next to the runway’s end to allow gliders to be marshalled and enable their tugs to manoeuvre alongside for mass take-offs.

The 53rd Troop Carrier Wing had set up its headquarters at nearby Bowdown House and took control of the groups at Aldermaston, Membury, Ramsbury, and Greenham. The 438th consisted of four squadrons, the 87th (3X), 88th (M2), 89th (4U) and 90th (Q7), each with 18 aircraft, which were primarily C-47s but also included a few C-53s. On D-Day itself, the 438th TCG had been selected to lead the IX TCC. Before operations commenced, General Eisenhower and 9th AF Commanding General Lewis Brereton visited Greenham on the night of 5 June to watch the final preparations. During this visit, Eisenhower gave his famous ‘Eyes of the world are on you’ speech to the troops.

|

At 22.48hrs on 5 June 1944, 81 aircraft took off at 11-second intervals from the airfield and transported 1,430 men of the 101st Airborne Division to Carentan, where they dropped just after midnight.

The armada of 800 aircraft was led by a C-47A of the 87th, 292847 “That’s All Brother” flown on the day by Lt Col J M Donalson (438th TCG Commander) and Lt Col David E Daniel (87th Squadron Commander). The aircraft had been modified to carry a GEE receiver in the fuselage to aid navigation to the drop zone. |

This C-47 survives today and is preserved by the Commemorative Air Force Central Texas Wing. Towards the end of May 2019, “That’s All Brother” crossed the Atlantic to take part in the 75th Anniversary of D-Day commemorations that were staged in England and France in early June 2019.

Following D-Day, Greenham’s squadrons continued to fly reinforcements. They towed gliders to the battle area along with supplies and brought back casualties when landing strips were established across the Channel. For their efforts, the 438th TCG received a Distinguished Unit Citation. In July 1944, a detachment from the 438th was sent to Canino airfield in Italy to take part in the invasion of Southern France (Operation Dragoon,) which commenced on 15 August 1944. From here, the Group’s aircraft dropped troops on the day of the invasion and undertook follow up Hadrian glider tows. While the resident units were away from Greenham, the 316th TGC used the airfield as a forward base until the end of August 1944, when the 438th returned.

|

Just after the elements of the 438th had left for Italy, Glenn Miller and his band arrived at Greenham to play a concert at Newbury’s Corn Exchange for the GIs. The event took place on 25 July 1944, where the band played well-known tunes, including In the Mood, String of Pearls, Pennsylvania 6-5000 and Moonlight Serenade.

Further operations took place in September 1944 as 90 aircraft of the 438th dropped elements of the 101st Airborne Division in the Eindhoven sector on the 17th of the month. These missions supported British and American airborne forces at Arnhem and Nijmegen, which was part of an operation known as Market Garden. |

The Allies aimed to create a salient into German territory to secure a crossing of the Rhine and thus an invasion route into the north of the country. The operation ultimately failed due to the Allies overextending themselves and with stiffer resistance than anticipated being met. Any chance of the war being over by Christmas had now evaporated. Re-supply and glider towing operations followed up the main attack, with the 439th and 442nd TCGs flying from Greenham, the 438th’s last glider tow was to Son on 23 September 1944.

The war was drawing near to ending, but Hitler still had some surprises up his sleeve. In December 1944, the Germans launched their last offensive in the west with an attack through the Ardennes, which caught the Allies completely off guard. The plan was to drive an attack through to the port of Antwerp, thus cutting off the Allied supply route. Bad weather hampered Allied air operations, and in what was to become known as the Battle of the Bulge, initial advances were made, but the Allies prevailed and pushed the offensive back. During this period, the 438th flew two missions to Bastogne to re-supply the troops on the ground. Hitler’s last gamble in the West had failed, and the German’s capacity to fight was now severely depleted, and they were unable to make good their losses.

The war was drawing near to ending, but Hitler still had some surprises up his sleeve. In December 1944, the Germans launched their last offensive in the west with an attack through the Ardennes, which caught the Allies completely off guard. The plan was to drive an attack through to the port of Antwerp, thus cutting off the Allied supply route. Bad weather hampered Allied air operations, and in what was to become known as the Battle of the Bulge, initial advances were made, but the Allies prevailed and pushed the offensive back. During this period, the 438th flew two missions to Bastogne to re-supply the troops on the ground. Hitler’s last gamble in the West had failed, and the German’s capacity to fight was now severely depleted, and they were unable to make good their losses.

On 12 December 1944, a tragedy occurred at Greenham when a Horsa glider crashed at the base, with the loss of 33 men of the US 17th Airborne Division. The cause of the accident was the detachment of the glider’s tail while in flight. Three days later, there was a further accident when two Boeing B-17G Flying Fortresses collided in bad weather over the airfield with the loss of 16 aircrew. The two aircraft were from USAAF Station 111 Thurleigh, 43-37633 of the 306th Bomb Group (BG)/368th Bomb Squadron (BS) and 43-38019 ‘Milk Run Special’, 306th BG/423rd BS were returning from an operation to Kassel Germany, the two pilots from 38019 survived the collision. A memorial once sited within Greenham Business Park was moved in August 2019 to a new location near the Control Tower, in remembrance of those lost in the Horsa and B-17 accidents.

In February 1945, the 53rd TCW HQ and its Groups, including the 438th, moved to Prosnes in France. This left ground elements of the USAAF at Greenham until the end of the war in Europe, after which the airfield was handed over to Transport Command, leaving a small detachment at the G-45 depot at Thatcham.

|

To the south of the airfield lies the estate of Highclere Castle, near to which is high ground. This terrain has claimed many aircraft that failed to clear its height. One was Boeing B-17G Flying Fortress 44-8436 'Fort Worth Jail House' of the 326th Squadron, 92nd Bomb Group USAAF Station 109, which crashed into Sidown Hill on 5 May 1945, with the loss of six of the seven crew on board. The B-17 was attempting to land at Greenham owing to poor weather. The crash was all the more tragic as the aircraft was on a training flight, the crew having completed all their missions with a return home imminent.

|

In August 1945, the airfield was transferred to Technical Training Command, with 13 Recruit Centre using the facilities for square bashing recruits, the first unfortunate youngsters arriving in September 1945, no doubt being subject to many shouted orders, marching and kit inspections.

Towards the end of World War Two, the future of flight was emerging in the form of jet-powered aircraft. In Britain, the first jet aircraft was the Gloster Meteor, which entered service just in time to see action before the war ended. Following on came the De Havilland Vampire. However, the transition from piston to jet power was not without its dangers, as this was a largely unexplored area of flight. Consequently, the test pilot's life for these new aircraft was fraught with danger, and it was at Greenham that this would come to pass for Sqn Ldr John Turner, a graduate of 1 Empire Test Pilot School Course.

Towards the end of World War Two, the future of flight was emerging in the form of jet-powered aircraft. In Britain, the first jet aircraft was the Gloster Meteor, which entered service just in time to see action before the war ended. Following on came the De Havilland Vampire. However, the transition from piston to jet power was not without its dangers, as this was a largely unexplored area of flight. Consequently, the test pilot's life for these new aircraft was fraught with danger, and it was at Greenham that this would come to pass for Sqn Ldr John Turner, a graduate of 1 Empire Test Pilot School Course.

|

On 12 September 1945, an accident occurred when De Havilland Vampire F.1 TG279 crashed near the station HQ, killing the pilot Sqn Ldr John Turner. Emerging from the cloud base at 5,000ft, the aircraft was seen to be diving at 45 degrees inverted before flattening out slightly and hitting the ground. There was no clear cause established to explain the crash, and this would by no means be the last accident that would occur when testing this new form of aircraft. As a result, many pilots were lost in the early years of jet-powered flight.

|

Following a number of Recruit Centre courses, Greenham was declared surplus and closed down on 1 June 1946. To all intents and purposes, this should have spelt the end of the airfield. But another conflict was on the horizon, the war may be over, but a new type of hostility was becoming apparent, the stand-off between East (the Soviet Union and its Allies) and West (NATO). This became known as the Cold War and continued well into the 1980s. The two sides never came to blows militarily, but they did fight proxy wars, such as in Vietnam and Afghanistan, which again cost many lives, both military and civilian. The power of the atomic bomb kept the two sides from attacking each other, as a nuclear war would have resulted in the destruction of both sides, something known as Mutually Assured Destruction, the acronym MAD was very apt.

The Americans required a number of strategic bomber bases in Britain, the UK government agreed to airfields being made available, one of which was Greenham Common. Teams from the US carried out surveys at the site during February 1951, and control passed to Bomber Command. In April 1951, the 7501st Air Base Squadron became the base administrator under the 7th AD, 3rd AF, United States Air Force Europe. The 804th Engineer Aviation Battalion moved in and began to rebuild the airfield. Formal handover to the 7th AD came on 18 June 1951. Many of the wartime buildings had been demolished to allow the construction of a 10,000ft (3048m) runway, which ran E/W on the line of the original. Taxiways and extensive hardstandings were laid, with a technical and domestic site built to the south side. The work necessitated the diversion of the A339 road through Packmoor Copse. It was not until September 1953 that all construction had been completed, after which it was declared the airfield was ready to receive Boeing B-47 Stratojets. The first use of the runway was made on 3 May 1951 when a Supermarine Attacker landed low on fuel. This was followed on 9 September of the same year when a De Havilland Vampire of 614 Squadron landed, again short on fuel. The Vampire F.3 in trail, VT799, was not so lucky and crashed southwest of Kingsclere when its fuel ran out with the pilot surviving.

The Americans required a number of strategic bomber bases in Britain, the UK government agreed to airfields being made available, one of which was Greenham Common. Teams from the US carried out surveys at the site during February 1951, and control passed to Bomber Command. In April 1951, the 7501st Air Base Squadron became the base administrator under the 7th AD, 3rd AF, United States Air Force Europe. The 804th Engineer Aviation Battalion moved in and began to rebuild the airfield. Formal handover to the 7th AD came on 18 June 1951. Many of the wartime buildings had been demolished to allow the construction of a 10,000ft (3048m) runway, which ran E/W on the line of the original. Taxiways and extensive hardstandings were laid, with a technical and domestic site built to the south side. The work necessitated the diversion of the A339 road through Packmoor Copse. It was not until September 1953 that all construction had been completed, after which it was declared the airfield was ready to receive Boeing B-47 Stratojets. The first use of the runway was made on 3 May 1951 when a Supermarine Attacker landed low on fuel. This was followed on 9 September of the same year when a De Havilland Vampire of 614 Squadron landed, again short on fuel. The Vampire F.3 in trail, VT799, was not so lucky and crashed southwest of Kingsclere when its fuel ran out with the pilot surviving.

Operational use began in March 1954, with 2,200 personnel moving in and a detachment of the 303rd Bomb Wing (BW) arriving from Davis Monthan Air Force Base with their B-47s. The basing of USAF bombers in Europe was part of Strategic Air Command’s (SAC) policy of deploying aircraft closer to the Soviet Union than the mainland United States, known as 'Reflex'. This was the first of 90-day rotations from the States, but there was a problem. The aircraft's weight caused damage to the runway, entailing the Wing was moved temporarily to RAF Fairford.

|

Work commenced on reinforcing the damage, and with this complete, the 3909th Air Base Group moved in during April 1956, with the airfield being designated for Boeing KC-97G Stratotanker deployments. During the works to strengthen the runway, 1,000ft extensions were laid at each end, and widening by 200ft was undertaken. It is considered that this was to allow the use of the Boeing B-52 Stratofortress that were then coming into service. Around the time Greenham was opened, the film Strategic Air Command was released and is well worth seeking out as it gives an excellent insight into what life was like on a typical SAC airfield.

|

|

In October 1956, the first full deployment of B-47s from the 310th BW arrived at Greenham. Forty-five aircraft were deployed to the airfield. However, due to the noise generated during take-off and landing, not to mention the ground running of engines and support equipment, local opposition increased. The situation was further worsened when on 28 February 1958, a B-47 experienced engine trouble on take-off, which necessitated the jettisoning of the aircraft’s two 1,700-gal underwing tanks.

|

An area was set up to allow for such an eventuality, but the pilots missed, and the tanks went astray. One tank landed on Hangar Two, where it exploded. The other hit a B-47 parked outside, where it burned for 16 hours. Help was summoned from RAF Odiham and USAF Welford to assist with the fire. The incident resulted in two men killed, eight injured, and two B-47s destroyed. With the runway obscured by smoke, the pilots of the troubled B-47 were unable to return to the airfield and flew on to Brize Norton, where a safe landing was made.

|

Reflex rotations continued, but with less flying taking place, this was to reduce noise and help local public relations. In October 1963, there was considerable excitement when Convair B-58A Hustler 12059 of the 305th BW, Bunker Hill AFB, flew to the airfield after taking part in Operation Greased Lightning.

The operation had entailed the aircraft flying from Tokyo to London in 8 hours 35 minutes at an average speed of 938mph, five hours of the flight had been at supersonic speeds. |

As the 1960s progressed, Strategic Air Command had at its disposal a far more extensive arsenal of weaponry in the form of aircraft with long ranges (such as the B-52), Intercontinental Ballistic Missiles (Atlas and Titan) and submarine-launched ballistic missiles (Polaris and Poseidon), all of which were less susceptible to Soviet attack than a fixed airfield. The B-47 was ageing, and it was announced in 1963 that the type would be withdrawn from use. A joint statement came in November 1963 from the Air Ministry and the USAF that the Americans would leave Greenham in 1964. The last B-47 took off from the airfield on 4 June 1964, and the base was formally closed on 30 June of the same year. Greenham was officially handed back to the RAF on 1 July 1964. However, with the Cold War far from over and instability still prevailing in various parts of the world, the decision was taken not to dispose of the airfield. RAF Welford made some use of the facilities.

In 1966 the French decided they no longer wanted to be part of NATO and expelled all American bases. A deadline of April 1969 was set, but the Americans decided they would leave by April 1967 and Operation FRELOC (French Relocation) was implemented. Some units went to West Germany while others came to Britain and located themselves at RAF Lakenheath, RAF Alconbury and RAF Mildenhall. This sudden influx of aircraft and personnel put an added strain on resources, and it was announced in January 1967 that Greenham, RAF Chelveston and RAF Sculthorpe would be brought back into use. The airfield was initially used as a storage facility for Welford, with all kinds of equipment being brought back from France until it was redistributed to other bases.

In 1966 the French decided they no longer wanted to be part of NATO and expelled all American bases. A deadline of April 1969 was set, but the Americans decided they would leave by April 1967 and Operation FRELOC (French Relocation) was implemented. Some units went to West Germany while others came to Britain and located themselves at RAF Lakenheath, RAF Alconbury and RAF Mildenhall. This sudden influx of aircraft and personnel put an added strain on resources, and it was announced in January 1967 that Greenham, RAF Chelveston and RAF Sculthorpe would be brought back into use. The airfield was initially used as a storage facility for Welford, with all kinds of equipment being brought back from France until it was redistributed to other bases.

|

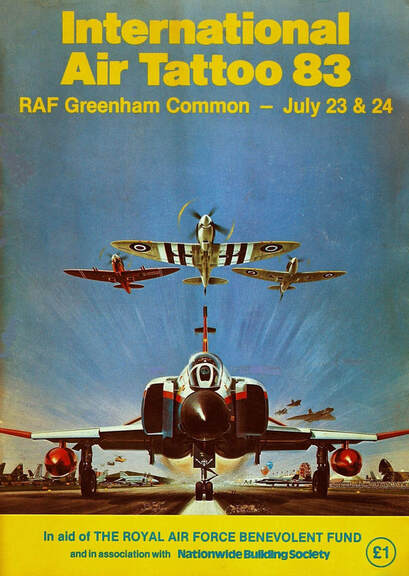

Greenham was upgraded to full-standby status on 1 November 1968 with the 7551st Combat Support Group (CSG) moving in for a stay of eight years. The role of the CSG was to keep the base in a functional state so that it could receive combat aircraft as and when the need arose. Over the coming years, Greenham saw a number of exercises being held and became home to the RAF Benevolent Fund’s International Air Tattoo, which took place in 1973, 1974, 1976, 1977, 1979, 1981 and 1983. Air forces from all over the world would attend the Tattoos and many types of aircraft displayed, including those in front line service and warbirds. The skies above the airfield would echo to the sounds of BAC Lightnings, Avro Vulcans, Lockheed F-104 Starfighters, Hawker Hunters, Supermarine Spitfire, Avro Lancaster and Hawker Hurricane as well as on one occasion, a Lockheed SR-71 Blackbird. Hard to think now when you visit the Common this ever happened.

|

|

In 1976 the runways of RAF Upper Heyford required resurfacing. As a result, the Bases resident General Dynamic F-111E bombers of the 20th Tactical Fighter Wing needed to find a new temporary home. Greenham was only a short distance away and fitted the bill. The deployment started in April 1976 and continued until August, with the F-111s undertaking regular training missions from the base.

During April 1977, discussions between the US 3rd AF and the MOD began regarding basing Boeing KC-135 Stratotankers at the airfield. |

During April 1977, discussions between the US 3rd AF and the MOD began regarding basing Boeing KC-135 Stratotankers at the airfield, causing a local uproar as the KC-135 at the time was an extremely noisy aircraft. Sixteen thousand people signed a petition which was presented to the House of Commons on 17 March 1978. In the end, concerns over the Atomic Weapons Establishment's close proximity came into play, as it was considered that the tankers would fly very close to the facility and could stray over it, which in turn would be a safety consideration. As a result, the decision was taken to send the KC-135s to RAF Fairford, which was without units, following the RAF’s withdrawal in 1971. There was also talk of TR.1s (high altitude reconnaissance aircraft) being located at the airfield, but in the end, they went to RAF Alconbury, interestingly it was also suggested that Greenham could become London’s third airport. On 1 January 1979, the 7273rd Air Base Group arrived, the first substantive unit to be based at the airfield for three years.

In October 1977, the Soviet Union began deployment of the 2,500-mile range SS-20 Intermediate-Range Ballistic missile. This caused concern as the weapon was mobile and could be moved to hit targets within NATO countries. To counter this threat, NATO decided to deploy ground-launched cruise missiles (GLCM) in Europe and on 17 June 1980, it was announced that Greenham Common and RAF Molesworth would be the two GLCM bases in Britain. The missile was a General Dynamics BGM-109G Gryphon, with a range of 1,550 miles and could carry a variable yield nuclear warhead of 10 to 50 kilotons. The ability of the Gryphon to fly at subsonic speed, along with terrane following capabilities, made it a challenging target for the Soviets to intercept.

In October 1977, the Soviet Union began deployment of the 2,500-mile range SS-20 Intermediate-Range Ballistic missile. This caused concern as the weapon was mobile and could be moved to hit targets within NATO countries. To counter this threat, NATO decided to deploy ground-launched cruise missiles (GLCM) in Europe and on 17 June 1980, it was announced that Greenham Common and RAF Molesworth would be the two GLCM bases in Britain. The missile was a General Dynamics BGM-109G Gryphon, with a range of 1,550 miles and could carry a variable yield nuclear warhead of 10 to 50 kilotons. The ability of the Gryphon to fly at subsonic speed, along with terrane following capabilities, made it a challenging target for the Soviets to intercept.

|

In 1981 work began preparing for the arrival of the missiles, including the construction of hardened shelters that could withstand a hit from a 2,000Ib bomb or a ten-megaton thermonuclear airburst detonated 1,600ft above. The six structures were to house the German manufactured MAN GLCM transporters with their support equipment and vehicles. The bunkers' site became known as the GLCM Alert and Maintenance Area (GAMA). In times of crisis, the GLCMs carriers would disperse to pre-planned locations in the English countryside, which reduced the missiles vulnerability to attack by hostile forces.

|

It is of interest to note that in 1981 Greenham was selected by NASA to act, if required, as a Trans-Oceanic Abort Landing (TAL) site for the Space Shuttle that was coming into service.

|

As could be expected, some were against nuclear weapons being based in the UK. On August bank holiday 1981, the first signs of a protest movement were seen, when around 25 people marched from Cardiff to Greenham. This was the beginning of a Women’s Peace Camp that was to be in place throughout the deployment and for some time after. There were frequent clashes between the protestors and the security forces over the coming years, and there were thoughts that the movement was infiltrated, in part, by elements of the Warsaw Pact.

|

Greenham became home to the 501st Tactical Missile Wing (TMW) and its operating unit, the 11th Tactical Missile Squadron (TMS). The 7273rd Air Base Group relinquished command of the base on 30 September 1982, and on the following day, the 501st raised their flag.

In May 1983, Lockheed C-5A Galaxy transport aircraft began to deliver equipment to the site, with the first GLCMs arriving at Greenham in the early morning of 14 November 1983 aboard a Lockheed C-141 Starlifter, further deliveries would take place in the following days.

In May 1983, Lockheed C-5A Galaxy transport aircraft began to deliver equipment to the site, with the first GLCMs arriving at Greenham in the early morning of 14 November 1983 aboard a Lockheed C-141 Starlifter, further deliveries would take place in the following days.

As the decade progressed, the political landscape was changing, and talks between the Americans and the Soviets in December 1987 resulted in an Intermediate Nuclear Forces Treaty (INF) agreement. The Treaty would entail both sides scrapping all Intermediate-range nuclear missiles, and for Greenham, this meant its GLCM role would be over by May 1991.

|

As part of the terms of the INF, Soviet arms inspectors were permitted to visit the base to verify the number of missiles and launchers present. They arrived for the first time in July 1988 aboard an Ilyushin IL-62.

The Soviets were allowed 24 hours to inspect but were not permitted to view the actual warheads. At the time, there were 96 missiles on-site plus five spares. |

In July 1989, the first four of Greenham’s GLCMs were taken aboard a C-5A and flown to Davis-Monthan for destruction, with the last missiles leaving on 5 March 1991. However, the inspectors continued to visit over the coming years, which concluded in 2001, when they were content that all the missiles had gone.

Further talk in 1988 proposed Greenham could become a base for squadrons of F-111s or maybe F-15E Strike Eagles, but events in 1989 in Germany saw East and West unite. When the Berlin Wall came down, the Cold War was coming to an end. In January 1990, the Department of Defense (DoD) announced further withdrawals from Greenham, RAF Fairford and RAF Weathersfield. The 501st TMS was dissolved on 31 May 1991, followed by the 501st TMW on 4 June the same year. The DoD decided to close Greenham by September 1992, the RAF had no further use for the base, and it ceased to be a military airfield in June 1992. To conclude matters, large crosses were marked at the runway ends to inform pilots that landings could no longer be made. The Americans left for good on 11 September 1991, as the Stars and Stripes were lowered for the last time.

The base was handed over to MOD land agents who set about disposing of the airfield, which would take many years to complete. The runways and taxiways were broken up, with most of the aggregate ending up as hardcore for building the A34 Newbury by-pass that was then under construction. The technical area was sold off and became known as the New Greenham Park industrial estate, the GAMA site was also sold and today is used as storage by private companies. The airfield has now returned to common land and is enjoyed as an area of recreation by walkers, runners and cyclists. The site is also a haven for wildlife and, with its commanding views over the Berkshire/Hampshire countryside, is truly a worthwhile place to visit. On 8 September 2018, the former Control Tower at Greenham was opened to the public as a museum and café, just the place for a coffee and cake after a wander around the Common.

Information relating to Greenham's Control Tower can be found here - https://www.airshowspresent.com/raf-greenham-common-control-tower.html

The base was handed over to MOD land agents who set about disposing of the airfield, which would take many years to complete. The runways and taxiways were broken up, with most of the aggregate ending up as hardcore for building the A34 Newbury by-pass that was then under construction. The technical area was sold off and became known as the New Greenham Park industrial estate, the GAMA site was also sold and today is used as storage by private companies. The airfield has now returned to common land and is enjoyed as an area of recreation by walkers, runners and cyclists. The site is also a haven for wildlife and, with its commanding views over the Berkshire/Hampshire countryside, is truly a worthwhile place to visit. On 8 September 2018, the former Control Tower at Greenham was opened to the public as a museum and café, just the place for a coffee and cake after a wander around the Common.

Information relating to Greenham's Control Tower can be found here - https://www.airshowspresent.com/raf-greenham-common-control-tower.html

Hidden within the trees towards the north of the airfield, Greenham's World War Two era bomb dump can be found - follow this link for information - https://www.airshowspresent.com/raf-greenham-common-world-war-two-bomb-dump.html

The last piece of Greenham's runway survives as a reminder to all that has gone before and is seen below in June 2019.

Sources

- In Defence of Freedom; a History of RAF Greenham Common - J J Sayers

- Action Stations 9 Central South and East - Chris Ashworth

- Airfields of the Ninth Then and Now - Roger A Freeman